The young “Knut” during his first explorations of an outdoor enclosure, 2007. (AZGB, image: Griesbach. All rights reserved.)

It’s something all Berlin Zoo employees have experienced: once other people find out where they work, one name comes up immediately: “Knut” – even though he died some time ago. There were almost 14,000 animals comprising some 1,300 species living at Berlin Zoo and Aquarium at the end of 2007. About 1,200 of them were mammals.1 Most of them had not been given names known to the public. Just like every year since its founding, there had been births at the zoo that year, including births of rare and popular animal species. And yet something quite special happened in 2007 and in the years that followed. The “Knut” phenomenon dominated news about the zoo in Berlin and even caused an international furore. How did this happen?

A Star Is Born!

On 5 December 2006, at about 3.00 pm, “Tosca” the polar bear gave birth to two cubs. It soon became clear that the mother was not going to properly care for the cubs. One of the cubs died. The other was removed from the enclosure and was successfully  fed by bottle.2 The two keepers and the curators in charge gave him the name “Knut”.

fed by bottle.2 The two keepers and the curators in charge gave him the name “Knut”.

Back then, it was not unusual for zoo-born baby animals to be raised by human hands using a bottle. But this polar bear cub soon became very special. In the following, we will see how “Knut” rapidly became a media star, causing a debate about the relationship between humans and animals and becoming a capital financial asset for the Berlin Zoo. This story also traces his transformation into an ambassador for environmental protection and into a popular companion for many people.

The story of “Knut” reveals a number of processes that have the potential to make one animal individual stand out from the great throng of animals living in Berlin’s zoos, including factors relating to economics, zoo history, environmental policy, media history, and social history.

Economies of Attention

By the end of his first year of life, Berlin’s polar bear cub had become an international  media star. Playing a major role in the popularity of this animal were the local media, in particular the regional ARD broadcaster Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB). Even before the animal had officially been presented to the public and while he was still being taken care of behind the scenes, the RBB was providing its listeners and viewers with daily updates from the zoo on the condition of the little bear and his relationship with his main caretaker, Thomas Dörflein, using video recordings made by keepers out of public view. Moreover, the RBB made use of its blog, www.rbb-online.de/knut, a relatively new medium back then. These daily updates on the RBB websites had a considerable influence on “Knut’s” growing fame. The editors at the RBB took the first-person perspective of a polar bear to write their blog entries, which they composed in the style of a child’s diary. Keeper Thomas Dörflein advanced in this medium to the role of “Papa”.3

media star. Playing a major role in the popularity of this animal were the local media, in particular the regional ARD broadcaster Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB). Even before the animal had officially been presented to the public and while he was still being taken care of behind the scenes, the RBB was providing its listeners and viewers with daily updates from the zoo on the condition of the little bear and his relationship with his main caretaker, Thomas Dörflein, using video recordings made by keepers out of public view. Moreover, the RBB made use of its blog, www.rbb-online.de/knut, a relatively new medium back then. These daily updates on the RBB websites had a considerable influence on “Knut’s” growing fame. The editors at the RBB took the first-person perspective of a polar bear to write their blog entries, which they composed in the style of a child’s diary. Keeper Thomas Dörflein advanced in this medium to the role of “Papa”.3

“Knut” and his “Papa” were a team that was easy for the media to market: on one side the clumsy ball of white fur, on the other the bearded man who moved in with his nursling and played him Elvis Presley songs on the guitar.

Keeper Thomas Dörflein and “Knut” when he was just a few months old, 2007. (AZGB, image: Bröseke. All rights reserved.)

But the story of the birth and the subsequent reporting in Berlin’s local media alone are not enough to explain the hype surrounding “Knut”. In 1957, a male gorilla infant arrived at the zoo. “Knorke” was in poor health when he arrived and had spent some time in a children’s hospital being cared for by two professors of paediatrics before a paediatric nurse took over his care. The images of “Knorke” and nurse Rosemarie were broadcast by the UFA Wochenschau newsreel and printed in numerous newspapers.

Nurse Rosemarie and “Knorke”, 1957. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

This young animal also went through a difficult period of hand-rearing at Berlin Zoo, where the media also found an attractive ‘sidekick’ in the form of Nurse Rosemarie Hohler. Many people certainly find both polar bear cubs and gorilla infants adorable.4 But “Knorke” did not generate nearly as much attention as “Knut”, not even after his early death in 1963. Taking a look at the zoo’s press archive shows that the news about “Knorke” did not exceed the normal level of reporting. Although the UFA Wochenschau announced the news of “Knorke’s” death nationwide, its interview with a zookeeper mainly revolved around the other gorillas at the zoo.5 There must be other factors at play than just the child-parent formula and hand-rearing to unleash real celebrity hype.

Discussions about Hand-Rearing

Another factor in “Knut’s” later fame were the discussions about zookeeping practices and the killing of young animals that was triggered by the killing of a sloth bear cub at Leipzig Zoo in late 2006. Just a few weeks after “Knut’s” birth, a sloth bear in Leipzig gave birth to a cub that she then rejected. The director of the zoo and his team decided to kill the young animal by ‘putting it to sleep’ after a number of attempts to motivate the mother to take care of her cub failed. According to the Leipzig Zoo management team, the cub would have died quickly and painfully in his natural habitat, and rearing the wild animal by hand was not species-appropriate. The German Animal Welfare Federation condemned the killing – also by making reference to the Berlin case of “Knut”.6

Conversely, one individual animal rights activist argued in relation to the Leipzig decision that raising animals by hand was not just species-inappropriate, but a blatant breach of the German Animal Welfare Act as well. For in Leipzig, zoo management had argued that the sloth bear cub would have grown up in poor physical and mental health. Berlin Zoo, he said, was allowing the polar bear to spend the rest of its life with behavioural problems. In the headline of a newspaper article about these accusations, a scandalising and anthropomorphising tendency becomes evident: “Animal rights activist: Cuddly Knut should have died!”7 The media were turning the predator born in human captivity into a stuffed toy. The Zoos in Leipzig and Berlin pointed out the differences between the two cases, but in the press and in the eyes of many observers, these two events were part of the same ethical context. “Is Knut becoming a problem bear?” asked Berlin’s Tagesspiegel8 in relation to the issue of his inevitable separation from his keeper, which would be traumatic for an animal that would have been intensively accompanied by his mother for many years in the wild.

The cub, which was now developing well, was not killed, and the press was then able to publish headlines like: “Polar bear cub escapes lethal injection”,9 and “Knut the polar bear allowed to live!”10 Although Berlin Zoo viewed these kinds of discussions sceptically, they increased the animal’s publicity. They would potentially elicit sympathy for the polar bear cub, which had now seemingly escaped death twice.

As Cord Riechelmann wrote in the Tageszeitung:

“In Knut’s case, the usual disdain that we feel for animals has morphed into an extreme urge to protect.”11

Riechelmann emphasised the way that humans exploited animals and said that this  exploitation had only seemingly been suspended, even in “Knut’s” case. In fact, there were also political and financial

exploitation had only seemingly been suspended, even in “Knut’s” case. In fact, there were also political and financial  economies at play in “Knut’s” case, which had an impact on the bear’s growing fame. For example, “Knut” was soon cast as a symbol of his threatened habitat.

economies at play in “Knut’s” case, which had an impact on the bear’s growing fame. For example, “Knut” was soon cast as a symbol of his threatened habitat.

Climate Protection Ambassador

German Federal Minister for the Environment Sigmar Gabriel flanked by keeper Thomas Dörflein, “Knut”, and Director Bernhard Blaszkiewitz, 2007. (AZGB, image: Bröseke. All rights reserved.)

“Knut” was born at a time when the first intense discussions were being held about the  climate crisis and threats to the polar bear’s natural habitat. The animal was well suited to playing the role of ambassador in the climate debate. With scientific forecasts predicting a decline in Arctic sea ice, polar bears had landed on the List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) the very same year that “Knut” was born.12

climate crisis and threats to the polar bear’s natural habitat. The animal was well suited to playing the role of ambassador in the climate debate. With scientific forecasts predicting a decline in Arctic sea ice, polar bears had landed on the List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) the very same year that “Knut” was born.12

However, Berlin’s polar bear was only able to achieve world fame due to a stroke of luck: shortly after the animal’s first public presentation in late March 2007, the state and government heads of the European Union converged on Berlin to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Rome Treaty. Representatives of the national and international press had arrived in the city with them. They were just as excited about the cub as the local press had been months earlier. “Knut” made headlines around the world. Surprised curators and zoo management staff gave hundreds of interviews that weekend.13 Moreover, tens of thousands of additional visitors made for an impressive scene. Security personnel had to control the rush at the outdoor enclosure. By early summer, a million guests had visited the zoo.14

“Knut” achieved global fame; even children from Cooper Station, NY, in the US wrote him letters with hand-drawn pictures. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

The zoo now wanted to take advantage of the intense interest in the bear for wildlife conservation. It created a brand that was used to sell licensed products. The earnings were funnelled into wildlife conservation projects.15 German Federal Minister for the Environment at the time, Sigmar Gabriel, was officially declared the little polar bear’s official sponsor. His ministry paid for a year’s upkeep at the zoo. The aim was to draw attention to global human-induced climate change.16

The “Knut” Brand

In spring 2008, there was even a film released in cinemas about the young polar bear and other animals.17 The German edition of Vanity Fair magazine put “Knut” on its cover in March 2007, while the American edition showed him in a photo montage on an ice floe with film star Leonardo DiCaprio, who had produced a film about climate change just that year.

Cover of the German edition of the magazine Vanity Fair, no. 14, 2007.

It was even possible to put a number on “Knut’s” economic value. In 2007, the zoo increased the earnings it generated from entry prices by about 40 per cent. Without the “Knut factor”, the zoo had expected earnings to grow by about 15 per cent in 2007.18 In March 2007, one expert estimated that the brand was worth seven to 13 million euro.19 The national media resonance and high visitor numbers doubled the buying price of zoo shares being traded at the time.20

According to zoo employees, while “Knut” was alive, there was a mobile kiosk that sold “Knut” souvenirs in front of the polar bear enclosure. Nothing like that has ever been seen at any other animal enclosures. Even when he grew into a polar bear ‘teenager’ after just a few months, “Knut” continued to attract many onlookers. When Zoo Director Bernhard Blaszkiewitz decided to bar the main keeper Thomas Dörflein from close contact with the bear for safety reasons, as he was now a danger to humans, his decision was criticised by “Knut” fans. Some of them were worried about the animal’s well-being, as “Knut” was now being kept in a shared enclosure with other members of his species instead of being in intensive daily contact with Thomas Dörflein and other keepers. But this did not harm the value of the brand. On “Knut’s” birthdays, the zoo was full, and vast crowds of visitors thronged in front of the enclosure, which can be seen in photos from the zoo’s archive.

The social scientist Guro Flinterud has described the contradiction evident here: keeping and breeding polar bears in  human captivity is a potentially unsuitable means of preventing habitat destruction, which is caused worldwide by the “physically unrelated actions” of the consumer industry. Reintroducing polar bears to the melting Arctic ice is almost impossible. It was therefore possibly the complexity of the climate crisis that fostered “Knut’s” “simple symbolism” in the first place.21

human captivity is a potentially unsuitable means of preventing habitat destruction, which is caused worldwide by the “physically unrelated actions” of the consumer industry. Reintroducing polar bears to the melting Arctic ice is almost impossible. It was therefore possibly the complexity of the climate crisis that fostered “Knut’s” “simple symbolism” in the first place.21

“Knut” Dies

On 19 March 2011, “Knut” fell into the moat of the polar bear enclosure and drowned. His cause of death remained uncertain for some time, until scientists at the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research determined that he died of an autoimmune disease. The outpourings of sympathy from Berlin’s residents and the international public was overwhelming. Once again, the zoo received boxes of letters from all over the world. In most of the letters, “Knut” fans both young and old expressed their grief. Hundreds of fans left their final messages in front of the polar bear enclosure and at the zoo fence.

Pictures, flowers, and final messages at the polar bear enclosure after “Knut’s” death, 2011. (AZGB, image: Bröseke. All rights reserved.)

In an online forum named “knutitis.com”, entries were posted in which great tenderness for the animal resounds together with utter distress about his death.22 One user said that “Knut” was part of her life. A group of Berlin residents collected money to erect a memorial stone at the Spandau cemetery In den Kisseln next to the grave of Thomas Dörflein, who had died in 2008.

However, alongside the outpourings of grief, “Knut’s” death also brought about accusations directed at the curator in charge, Heinz-Georg Klös, and the zoo’s director, Bernhard Blaszkiewitz. One woman, who wished to remain anonymous, wrote to the zoo in March 2011:

“You brutal, merciless zoo people! May God punish you // Knut! Bullied to death // Murderers = Klös + Blaszkiewitz!”

The author’s emotions were so strong that she sent a number of letters. Critics like her claimed that being put into an enclosure with three older polar bear females might have caused “Knut” stress. President of the German Animal Welfare Federation Wolfgang Apel accused zoo director Bernhard Blaszkiewitz of being more interested in his reputation than animal welfare and demanded that an end be put to polar bear breeding.23 One criticism of the zoo that had already announced itself during the discussions of hand-rearing in 2006/2007 grew louder once again, relating to the fundamental issue of whether zoos should stop breeding polar bears altogether.24

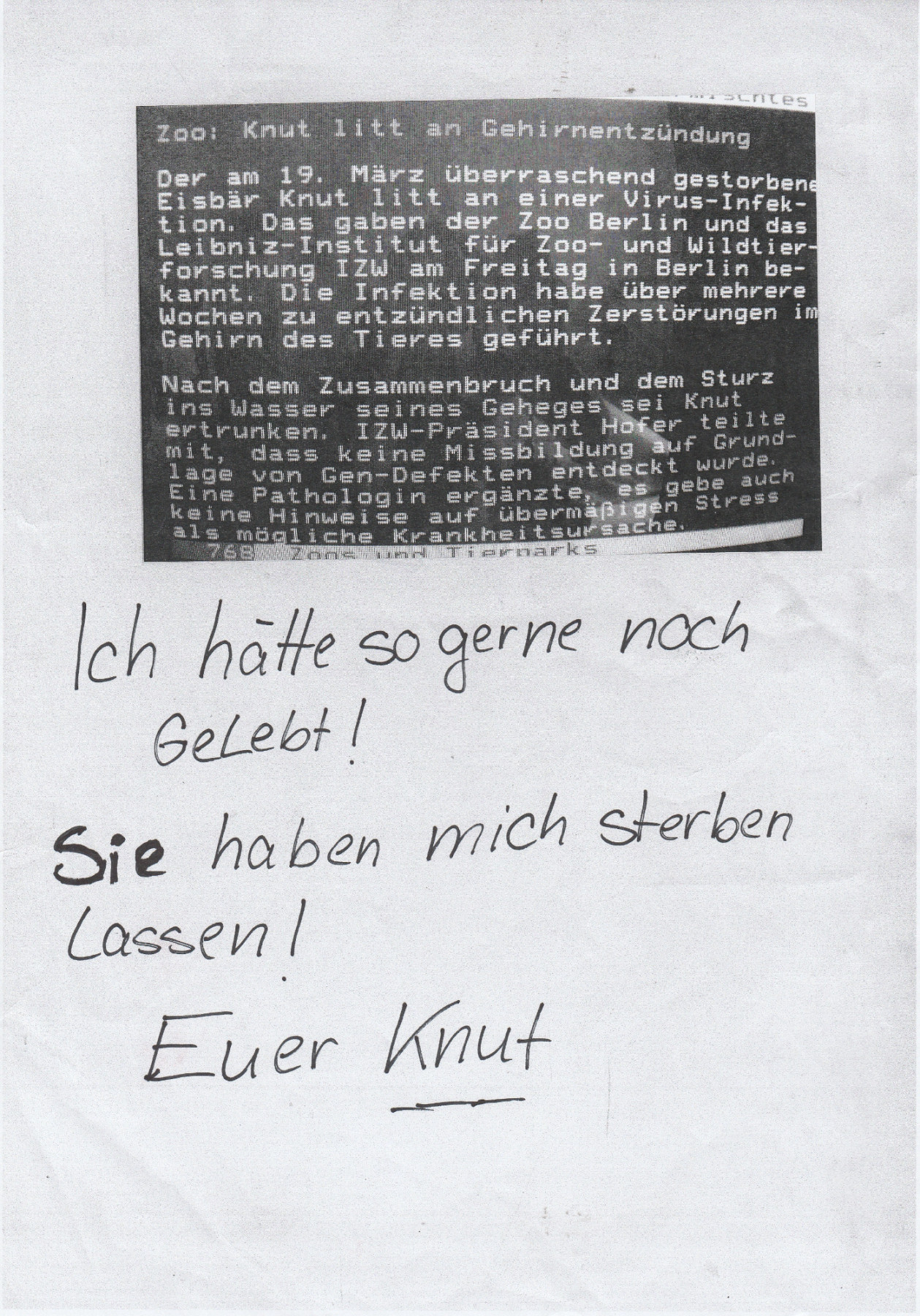

For a number of “Knut” fans, however, this issue was limited to the housing conditions of a single animal. Some authors assumed the viewpoint of the dead animal in their letters, directly addressing the director as “Knut” himself.

Fax with allegations against zoo management, 2011. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

In 2012, the sculpture “Knut the Dreamer” was erected in the zoo, based on a design by the artist Josef Tabachnyk. The roughly 1.5-metre-long and a little over one-metre-wide structure at the polar bear enclosure shows a polar bear cast in bronze lying on two ice floes made from white granite – ice floes that the animal had never seen while he was alive.25

Sculpture “Knut the Dreamer”, 2021. (Image: Clemens Maier-Wolthausen. All rights reserved.)

Donations to erect the monument were collected by the Capital City Zoos Foundation (Stiftung Hauptstadtzoos). Moreover, in 2012, replicas of the sculpture were sold as souvenirs. The sculpture, described as a memorial, was also the motif on a bronze-plated commemorative coin issued by Berlin’s State Mint.26 Flowers, letters, and pictures are regularly left at the sculpture on the birthdays and death anniversaries of “Knut” and Thomas Dörflein. This honour is not bestowed on any other zoo animals.

“Knut’s” Death and Taxidermy

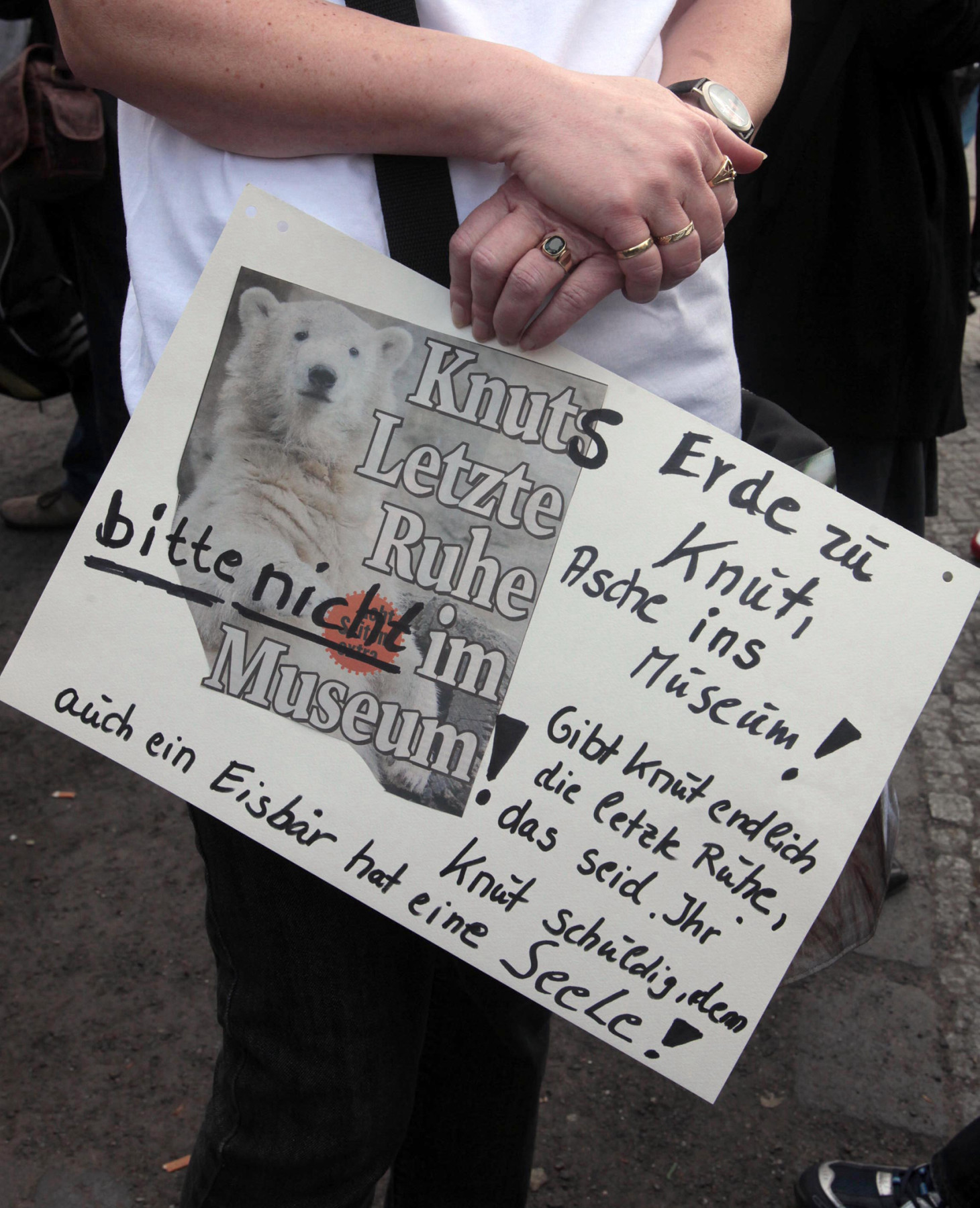

Shortly after the polar bear’s death, the decision was made to bring “Knut’s” cadaver to the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, where he would be mounted as a taxidermy and would continue to serve natural history education as an  exhibit. Angry protests about his continued display flared up among “Knut” fans. The zoo once again received numerous letters, many of which described its actions as impious. This came to a head with a demonstration at the zoo’s entrance at Hardenbergplatz. Photos from the zoo archive show demonstrators with posters like this one:

exhibit. Angry protests about his continued display flared up among “Knut” fans. The zoo once again received numerous letters, many of which described its actions as impious. This came to a head with a demonstration at the zoo’s entrance at Hardenbergplatz. Photos from the zoo archive show demonstrators with posters like this one:

“Children ask… Why can’t Knut go to heaven? // Mother thinks: Because they need him to make money… // Mother says: Knut will be okay… // We don’t want to have to lie to our children to protect them!!!! // This is why we are demanding that Knut’s body be left alone and for him to finally find some peace.”

Or:

“Earth to Knut, ashes to the museum! Give Knut a final resting place, you owe it to him, because even a polar bear has a soul!”

Protest banner against “Knut’s” taxidermy, 2011. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Knut was ultimately mounted, and his  taxidermy can still be viewed at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin today.

taxidermy can still be viewed at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin today.

“Knut” and the taxidermist Detlev Matzke in the taxidermy workshop of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, 2013. (Image: Carola Radke/MfN. All rights reserved.)

“Knut” being exhibited at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, 2013. (Image: Carola Radke/MfN. All rights reserved.)

“Knut” Forever

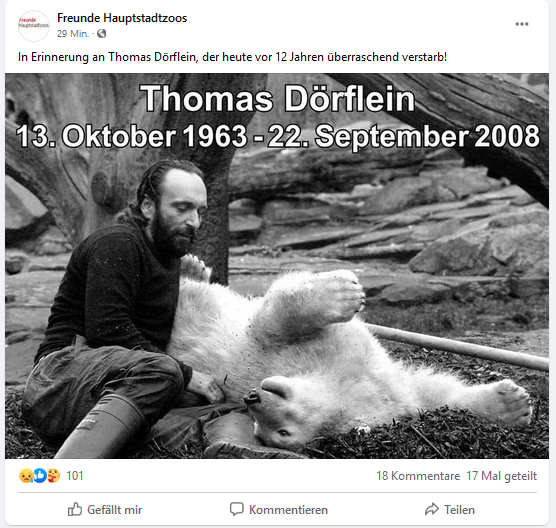

In 2020, the topic of “Knut” and Thomas Dörflein still had the potential to create a stir. On the twelfth anniversary of the death of Thomas Dörflein, the Friends of the Capital City Zoos Association (Förderverein der Freunde der Hauptstadtzoos) commemorated the death of “Knut’s” keeper.

Facebook post of the association Friends of the Capital City Zoos Association on Facebook, 22.09.2020

The many comments on this post and reactions to it show that this topic still has an emotional impact on visitors to the zoo. Almost all of the comments contain emojis with tears, hearts – often broken – and similar visual representations of grief and pain about the death of Thomas Dörflein. However, most of the comments refer to his ward and to the fact that “Knut” would be remembered just as much as Thomas Dörflein. The perceived  symbiosis between the keeper and his nursling, and their combined emotional value, carried beyond their deaths and still had the capacity to mobilise emotions twelve and nine years after their deaths respectively.

symbiosis between the keeper and his nursling, and their combined emotional value, carried beyond their deaths and still had the capacity to mobilise emotions twelve and nine years after their deaths respectively.

While this text was being written in the summer of 2021, Berlin Zoo received a copy of a self-published book.27 The author had already self-published another book, Knut: The Bear, the City, and the Zoo in 2013 about the life of the polar bear.28 The 2020 book – a collection of texts, annotated photos probably taken by the author herself, and newspaper clippings – is predominantly written in the present tense. This seems somewhat unusual for an animal that died almost ten years ago. It announces a sequel, for the book ends while Knut is still a cub. But perhaps the grammatical present here is a translation of the emotional level. For some people, “Knut” is still present.

“Knut” and the Factors in his Fame

So far, the protests about “Knut’s” taxidermy have been one of a kind, even though this extremely popular zoo animal was not the first animal to be exhibited at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin after its death. Unlike in “Knut’s” case of 2013, there is no discussion to be found in the zoo’s press archive, for example, in 1935 about exhibiting the extremely popular gorilla  “Bobby”. Nor was the 1988 taxidermy of the famous hippopotamus “Knautschke” contentious. It is likely that “Knautschke” came to Berlin Zoo in 1942 as a calf, and he was one of the few large animals that survived the war at the zoo. He had been fed throughout the postwar period and during the Berlin Blockade by Berlin’s residents. As a symbol of a community united during

“Bobby”. Nor was the 1988 taxidermy of the famous hippopotamus “Knautschke” contentious. It is likely that “Knautschke” came to Berlin Zoo in 1942 as a calf, and he was one of the few large animals that survived the war at the zoo. He had been fed throughout the postwar period and during the Berlin Blockade by Berlin’s residents. As a symbol of a community united during  scarcity, there were numerous anecdotes circulating about him. But in spite of the animal’s obvious fame and popularity, an exhibition at the Berlin City Museum of a plaster model that also contained taxidermies of some of the animal’s body parts was not met with any criticism in the 1980s. The model provided a template for a 1998 sculpture of “Knautschke” – now used by children as a stage for photographic mementos in front of the hippopotamus house at the zoo, although it has never attained the status of memorial.

scarcity, there were numerous anecdotes circulating about him. But in spite of the animal’s obvious fame and popularity, an exhibition at the Berlin City Museum of a plaster model that also contained taxidermies of some of the animal’s body parts was not met with any criticism in the 1980s. The model provided a template for a 1998 sculpture of “Knautschke” – now used by children as a stage for photographic mementos in front of the hippopotamus house at the zoo, although it has never attained the status of memorial.

Just like “Knautschke’s” taxidermy, an exhibit at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin featuring “Bao-Bao”, the 34-year-old panda from the Zoological Garden that died in 2012, did not lead to any controversies, as can be garnered by reviewing the press from that time, even though the giant panda had long been a reliable audience magnet for Berlin Zoo. Visitors, friends of the zoo, and the press had shared in the failed breeding attempts and the fate of the two panda females “Tien-Tien” and “Yan-Yan”, who both died before “Ba-Bao”29 and who were also mounted as natural history showpieces. While the Tagesspiegel was still asking in 2013 whether the deployment of “Knut’s” taxidermy in the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin was “A symbol? An idol? Or just a taxidermy?” the exhibition of all three Berlin pandas was described in 2015 as a “celebration” of the dead stars.30

Not even the 1972 taxidermy of the panda female “Chi-Chi” in London stimulated discussion, although the case was different for London Zoo’s gorilla “Guy” in 1978. The zoo and the museum received letters protesting his taxidermy. In the case of “Guy”, the primate studies carried out by Dian Fossey and Jane Goodall and their dissemination in the media might have played a role. For some Londoners, “Guy” was too human to be stuffed.31 Maybe this is another key to understanding “Knut’s” status, even though he was of a different species.

This kind of sustained enthusiasm for a zoo animal has not been seen on this scale since, neither for the polar bear cub “Björn-Heinrich”, born on 7 November 1986 at Tierpark Berlin and named after Tierpark director Heinrich Dathe, nor for the polar bear cub “Flocke”, born in Nuremberg in 2010. Both of them, like “Knut”, were raised by hand. And not even “Hertha”, born in 2018 at Tierpark Berlin, the zoo in the Berlin district of Lichtenberg, was able to achieve the same popularity as “Knut”. It seems like the male polar bear cub – and his keeper – filled a niche in 2007 and the years that followed, that they satisfied a special craving. “Knut’s” story and the celebrity that took shape around him thus remain unusual – so unusual that the hype surrounding “Knut” has also roused academic interest since his death in 2012. Guro Flinterud, who wrote her doctoral thesis on the “Knut” phenomenon in Oslo – Norway was also interested in Berlin’s polar bear – describes her encounters with the “Knut” fans, “Knutians”, who came together in 2010 on a cold winter’s day in the polar bear enclosure. Many of them were annual ticket holders and had already been visiting the zoo regularly before “Knut” was born.

“What was special now that Knut was there was that they did not just come to look at animals; their zoo trips had become more of a social experience. It was not just about going to the zoo per se, but also about meeting new friends and gaining a whole new circle of acquaintances. […] Through following Knut […] they had something to start the conversation, and suddenly they were less alone; in their connection with Knut they found a group of people with whom to share this connection.”

Would these connections and their shared interest still have come about in a world without (social) media? In 2007, “Knut” was omnipresent in both Berlin and beyond. But it was not just “Knut’s” presence in the media but also the way that the animal was anthropomorphised from the beginning due to his hand-rearing by ‘Papa’ Thomas Dörflein that had long-term consequences. “Knut” interacted with his keepers and, by way of the cameras, with a broader public. By extension, he also played a role in the creation of his celebrity status. Everything he had done, as Guro Flinterud argues, had been seen more in relation to the people around him than within the context of the animal itself.32

Can we find the reason behind “Knut’s” special status by looking at media history? If so, then there will be no other “Knut”. Zoos – and Berlin Zoo as well – are increasingly making efforts to keep animals away from direct human contact, in what is referred to as protected contact management, which is intended to ensure the safety of animals but also keepers. This form of management seems more natural to visitors, although the animals are subject to rules that are just as strict. It would therefore be difficult to reproduce the mechanisms of celebrity described here.

Environmental politics are another factor that would be difficult to reproduce today. The climate crisis is no longer news, and zoos are now stylising themselves more intensively as wildlife  conservation centres in their communications and are also perceived by many Germans that way.33 This suggests that there is no longer as much room left for the ambassador of a single species in this kind of communication. However, once all of these factors fade away, it is very difficult to imagine that the construction of a

conservation centres in their communications and are also perceived by many Germans that way.33 This suggests that there is no longer as much room left for the ambassador of a single species in this kind of communication. However, once all of these factors fade away, it is very difficult to imagine that the construction of a  celebrity like “Knut” will repeat itself. The polar bear cub united important moments in media and zoo history with environmental-political and economic interests. “Knut” provides a snapshot of the potential inherent to zoo animals to activate broad public interest and strong emotions. However, zoos cannot generate this interest and these emotions by themselves. For that, more protagonists are required.

celebrity like “Knut” will repeat itself. The polar bear cub united important moments in media and zoo history with environmental-political and economic interests. “Knut” provides a snapshot of the potential inherent to zoo animals to activate broad public interest and strong emotions. However, zoos cannot generate this interest and these emotions by themselves. For that, more protagonists are required.

- Zoologischer Garten Berlin AG. “Geschäftsbericht für das Jahr 2007” Bongo 38 (2008): 91-196, 139-140.↩

- Zoologischer Garten Berlin AG: Press releases 04/07, 22.01.2007, and 15/07, 28.02.2007.↩

- Cf. Guro Flinterud and Adam Dodd. “Polar Bear Knut and his Blog”. In Animals on Display: The Creaturely in Museums, Zoos and Natural History, Liv Emma Thorsen and Karen A. Rader (eds.). University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013: 192-213; Flinterud, Guro. “A Polyphonic Polar Bear: Animal and Celebrity in Twenty-first Century Popular Culture”. Thesis. University of Oslo, Faculty of Humanities, 2012: 133-136.↩

- Jürg Meier. Handbuch Zoo: Moderne Tiergartenbiologie. Bern, Stuttgart, and Vienna: Haupt Verlag, 2009: 117-118.↩

- These segments can be found on the website of the German Federal Film Archives: https://www.filmothek.bundesarchiv.de/?set_lang=en (03.01.2022).↩

- “Tötung eines kleinen Lippenbären löst Empörung aus”, Tagesspiegel-online, 29.12.2006, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/panorama/leipziger-zoo-toetung-eines-kleinen-lippenbaeren-loest-empoerung-aus/792414.html (25.01.2022).↩

- “Tierschützer: Knuddel-Knut hätte sterben müssen!” Rheinische Post Online, 19.03.2021, https://rp-online.de/panorama/deutschland/tierschuetzer-knuddel-knut-haette-sterben-muessen_aid-11295343?output=amp (03.01.2022).↩

- Anette Krögel. “Wird Knut ein Problembär?” Der Tagesspiegel online, 20.03.2007, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/wird-knut-ein-problembaer/824706.html (03.01.2022).↩

- “Eisbärbaby Knut entkommt der Todesspritze”. Welt Online, 19.03.2007, https://www.welt.de/vermischtes/article768024/Eisbaerbaby-Knut-entkommt-der-Todesspritze.html (03.01.2022).↩

- “Eisbär Knut darf leben”. Merkur.de, 01.07.2007, https://www.merkur.de/welt/eisbaer-knut-darf-leben-377265.html (03.01.2022).↩

- Cord Riechelmann. “Lass uns über Produktion reden”. Die Tageszeitung, 14.04.2007.↩

- “Flußpferd und Eisbär Neuzugänge auf Roter Liste”. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Online, 02.05.2006, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wissen/natur/artensterben-flusspferd-und-eisbaer-neuzugaenge-auf-roter-liste-1330020.html (03.01.2022).↩

- The interviews are listed in the zoo’s daily logbook for March 2007.↩

- Zoologischer Garten Berlin AG: Press release, 44/07, 04.07.2007.↩

- Zoologischer Garten Berlin AG and Universal Music: Press release, 25/07, 17.04.2007.↩

- Sigmar Gabriel. “Kann Knut den Klimawandel bremsen?” In Das große Knut-Album, ed. by B.Z. extra, 49. Berlin: B.Z., 2007: 49.↩

- “Knut und seine Freunde”, dir. by Michael G. Johnson, prod. by DOKfilm Fernsehproduktion GmbH, Norddeutscher Rundfunk, Rundfunk Berlin Brandenburg, 2008.↩

- Guro Flinterud. “A Polyphonic Polar Bear: Animal and Celebrity in Twenty-first Century Popular Culture”. Thesis. University of Oslo, Faculty of Humanities, 2012: 112.↩

- “Als Marke ist Knut Millionen wert”. Spiegel Online, 31.03.2007, https://www.spiegel.de/panorama/gesellschaft/berliner-eisbaerenbaby-als-marke-ist-knut-millionen-wert-a-475021.html (03.01.2022).↩

- “Knut begeistert Aktionäre”. Spiegel Online, 03.04.2021, https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/berliner-zoo-knut-begeistert-aktionaere-a-475415.html (03.01.2022).↩

- Guro Flinterud. “A Polyphonic Polar Bear: Animal and Celebrity in Twenty-first Century Popular Culture”. Thesis. University of Oslo, Faculty of Humanities, 2012: 208-209.↩

- The forum describes itself as follows: “knutitis.com is a meeting place for Knut fans from all over the world. The focus is, of course, on Knut the polar bear. But you can also come here to talk about other zoo animals and zoos. We are a group of animal enthusiasts from all over the world who met through Knut and who have since become friends. We are committed, enthusiastic, and maybe even a little crazy.” www.knutitis.com (03.01.2022).↩

- “Knut-Tod: Vorwürfe an Zoo-Chef”. Neue Presse Online, 25.03.2011, https://www.neuepresse.de/Nachrichten/Panorama/Knut-Tod-Vorwuerfe-an-Zoo-Chef (03.01.2022).↩

- Cf. Hucklenbroich, Christina. “Knut und die Knutianer”. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Online, 01.04.2011, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/tod-im-zoo-berlin-knut-und-die-knutianer-1606570.html (03.01.2022).↩

- Cf. “Denkmal für Eisbär Knut im Zoo”. Berlin.de, https://www.berlin.de/tourismus/zoos-und-tierparks/eisbaer-knut/2315669-1694342.gallery.html?page=4 (03.01.2022).↩

- “Denkmal für Knut”. Münz-Woche, 15.03.2012, https://muenzenwoche.de/denkmal-fuer-knut/ (03.01.2022).↩

- Anneliese Klumbies and Jürgen Simoleit. Hier kommt Knut! Eine wahre Geschichte. Hamburg: self-published, 2020.↩

- Anneliese Klumbies. Knut: Der Bär, die Stadt und der Zoo. Hamburg: self-published, 2013.↩

- Cf. Ferdinand Damaschun, ed. Panda: Das Buch zur Sonderausstellung im Museum für Naturkunde. Berlin: Museum für Naturkunde, 2015.↩

- Bernd Matthies. “Ein Bär kann auch leger”. Der Tagesspiegel, 16.02.2013; Conrad, Andreas. “Berliner Bärenlese”. Der Tagesspiegel, 12.01.2015, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/pandas-im-museum-berliner-baerenlese/11219278.html (03.01.2022).↩

- Henry Nicholls. “The Afterlife of Chi-Chi”. In The Afterlives of Animals: A Museum Menagerie, Samuel J. M. M. Alberti (eds.). Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011.↩

- Guro Flinterud. “A Polyphonic Polar Bear: Animal and Celebrity in Twenty-first Century Popular Culture”. Thesis. University of Oslo, Faculty of Humanities, 2012: 239-245.↩

- Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. “Die Deutschen und ihre Zoos: Ergebnisse der Forsa Studie”. VDZ, 2020, https://www.vdz-zoos.org/fileadmin/PMs/2020/VdZ/Forsa-Broschuere_Die_Deutschen_und_ihre_Zoos.pdf (03.01.2022).↩