The antelope house at Berlin Zoo, around 1920. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Paragraph 42 of the German Act on Conservation and Landscape Preservation (BNatSchG) defines zoos as

“permanent fixtures in which live animals belonging to wild species are kept for a period of at least seven days per year for the purpose of putting them on display”.

The legislature thus distinguishes zoos from circuses and pet shops while simultaneously describing the main purpose of a zoo quite precisely: to put animals on display, i.e., to show them.

There must be a reason for putting animals on display like this. There must be grounds for keeping animals in human captivity and showing them in public. For zoological gardens and their sponsors, it is often an expensive enterprise, and they have to provide ethical justifications for keeping animals – as they had to for  catching them in the past. What purposes has keeping animals in zoos served in the eyes of zoo management and visitors, both in the past and today?

catching them in the past. What purposes has keeping animals in zoos served in the eyes of zoo management and visitors, both in the past and today?

Changing Objectives and Purposes

In premodern times and up into the period of absolutism, the main reason for keeping wildlife was to privately entertain rulers or to  flaunt their power.1 Conversely, the zoos founded over the course of the 19th century, claimed that they were serving other purposes. The Bronx Zoo was intended to serve as a breeding facility for endangered American animals and London Zoo as a site of

flaunt their power.1 Conversely, the zoos founded over the course of the 19th century, claimed that they were serving other purposes. The Bronx Zoo was intended to serve as a breeding facility for endangered American animals and London Zoo as a site of  scientific research.2

scientific research.2

Martin Hinrich Lichtenstein was the founding director of Berlin’s Zoo, the oldest in Germany, as well as director of the Zoological Museum and Professor of Zoology at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin. Lichtenstein applied to the Prussian King Frederick William IV to establish an “institution” (Anstalt) that would be tasked with “breeding and proliferating beautiful and useful animals, [and] refining our  domestic animals”.

domestic animals”.

“Satisfying the inquisitiveness and curiosity of the people […] would thus be merely a secondary purpose, but not an insignificant one, because it is precisely by fulfilling this purpose that it will be possible to ensure its permanent existence in and through itself.”3

Exhibiting and looking at live animals was, as these words make clear, merely a secondary effect that would secure the financial upkeep of the institute, but (supposedly) not the focus. The 1869 charter of the stock association of the Zoological Garden of Berlin (Aktien-Vereins des Zoologischen Garten), however, set out the zoo’s purpose as follows:

“The association tasks itself with maintaining and completing the collection of live animals at the zoological garden, with promoting scientific observation and examination, as well as artistic studies in the field of zoology, and with disseminating scientific knowledge, namely by encouraging the instruction of youth.”4

The zoo now had a myriad of purposes to fulfil. In 2012, about 170 years after the first German zoo was opened in Berlin, the Association of German Zoo Directors (Verband Deutscher Zoodirektoren), now the German Association of Zoological Gardens (Verband der zoologischen Gärten), described the main tasks of zoos in reference to the biologist Heini Hediger as:

recreation – teaching and education – research – conservation.5

Hediger, a zoologist and director of the zoos in Bern, Basel, and Zurich, had established the field of zoo biology after the  end of the Second World War. Conservation for him meant breeding species that were threatened in their own habitats.6

end of the Second World War. Conservation for him meant breeding species that were threatened in their own habitats.6

The following will describe the purposes of putting animals in human captivity on display that have long been accepted by most zoological gardens and reveal their reciprocal influences and trajectories. It will become evident that it is almost impossible to clearly distinguish between the  perspectives and self-understandings of zoo management and visitors.

perspectives and self-understandings of zoo management and visitors.

Recreation: Entertainment and Spectacle

After founding their zoological gardens, it became clear to many zoo directors – almost exclusively  men up until late in the 20th century – that the throngs of visitors required to pay for the upkeep of zoos would not be coming to see native animals.

men up until late in the 20th century – that the throngs of visitors required to pay for the upkeep of zoos would not be coming to see native animals.

“The masses – at the zoo, they were not the educated bourgeois, who sought educational entertainment in line with the intended objectives, but those who wanted to see a spectacle.”7

And this spectacle would not be produced with domestic cattle. The French historian Eric Baratay writes:

“The public wanted to see rare, wild predators, unlike European species, to divert themselves and dream of distant lands. Zoological gardens were a substitute for travelling and satisfied their longing for the ‘exotic’, which in the Western world grew stronger and stronger with Romanticism, research expeditions, and colonial adventures, enticing elites to travel to faraway places.”8

Although they had limited funds, the first zoo directors in Berlin attempted to obtain animals from other continents to meet visitor’s ‘exotic’ expectations. From the very beginning, this was accompanied by another aspect of the zoo’s character as a place of adventure and recreation, where the showing of animals and even the sometimes permitted  touching of the animals more or less disappeared into the background: restaurants and refreshment areas, an opportunity to meet,

touching of the animals more or less disappeared into the background: restaurants and refreshment areas, an opportunity to meet,  eat, and enjoy the company of others. For some, we might surmise, the animals on display formed a backdrop, an alibi for the real enjoyment. At the Berlin zoo, restaurants were being continually expanded at the public’s request, with the result that, in 1911, the zoo was home to the largest restaurant not just in the city, but probably in Europe, with more than 10,000 seats.9 It also provided a setting for concerts of military music and grand balls.

eat, and enjoy the company of others. For some, we might surmise, the animals on display formed a backdrop, an alibi for the real enjoyment. At the Berlin zoo, restaurants were being continually expanded at the public’s request, with the result that, in 1911, the zoo was home to the largest restaurant not just in the city, but probably in Europe, with more than 10,000 seats.9 It also provided a setting for concerts of military music and grand balls.

The Emperor’s Hall at the zoo restaurant, around 1910. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Announcement for Opera Ball at the zoo restaurant, 1914. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

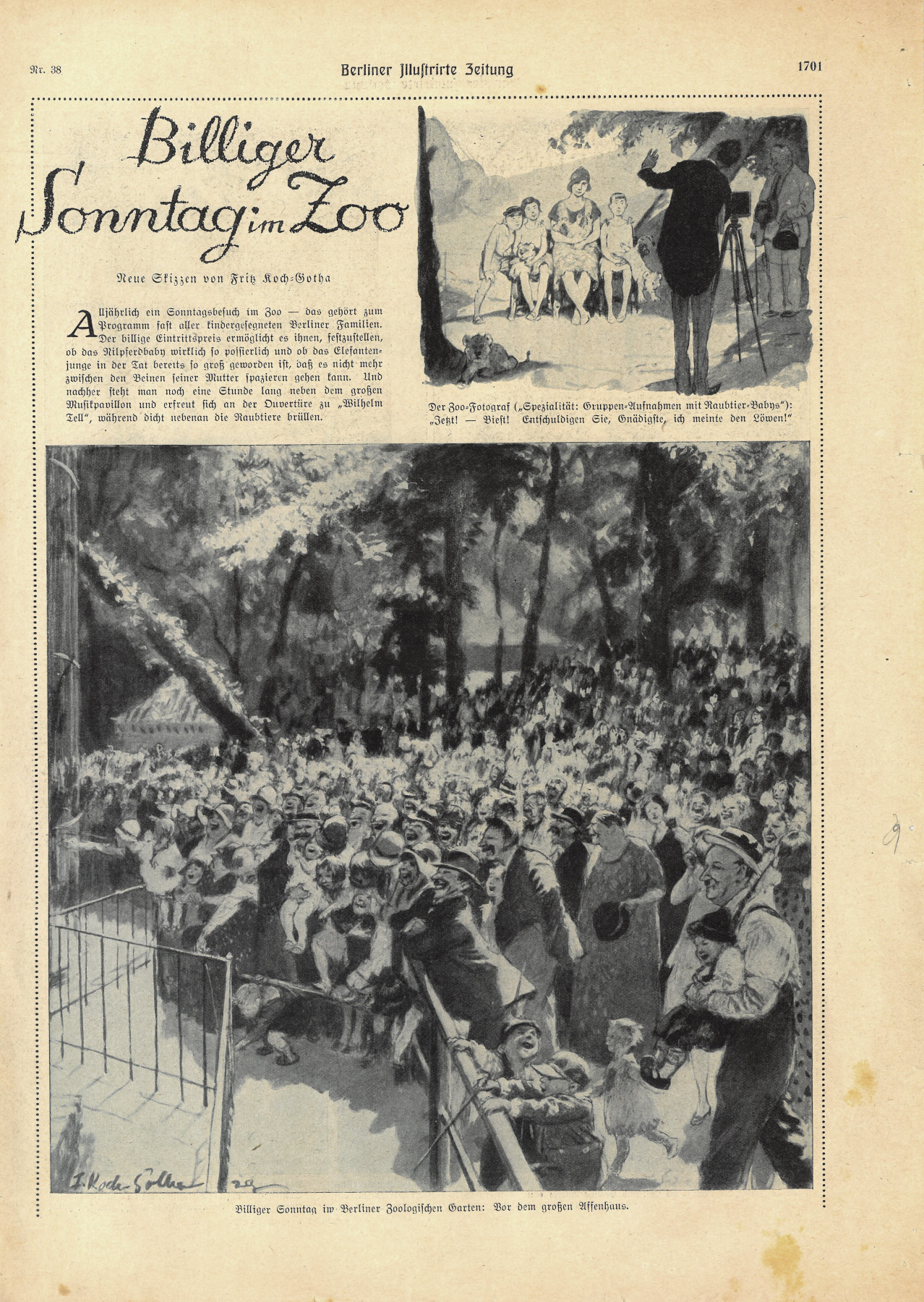

For the public, seeing and being seen became just as much a reason for going to the zoo as  observing animals and acquiring knowledge about natural history. On the central axes through the zoo, between the Elephant Gate and the entrance at the Zoological Garden train station, bourgeois zoo shareholders, members of the educated bourgeois classes, and the civil servants of the Prussian state had the opportunity to solidify their status and their networks by visiting the zoo. For the workers from the suburbs in the east of Berlin, ‘cheap Sundays’ were introduced shortly after the zoo’s founding, with the price of entry tickets reduced by half. According to newspaper reports of the time, the zoo was full on those days, and the less wealthy members of the public took their refreshments at the more affordable gastronomic facilities with beer instead of champagne, and pretzels instead of caviar.10 The goal for all visitors was recreation, to take a step out of their everyday lives and into another world.

observing animals and acquiring knowledge about natural history. On the central axes through the zoo, between the Elephant Gate and the entrance at the Zoological Garden train station, bourgeois zoo shareholders, members of the educated bourgeois classes, and the civil servants of the Prussian state had the opportunity to solidify their status and their networks by visiting the zoo. For the workers from the suburbs in the east of Berlin, ‘cheap Sundays’ were introduced shortly after the zoo’s founding, with the price of entry tickets reduced by half. According to newspaper reports of the time, the zoo was full on those days, and the less wealthy members of the public took their refreshments at the more affordable gastronomic facilities with beer instead of champagne, and pretzels instead of caviar.10 The goal for all visitors was recreation, to take a step out of their everyday lives and into another world.

Article about ‘Cheap Sundays’ at the Berlin Zoo in Berliner Illustrierten Zeitung, no. 38, 1929.

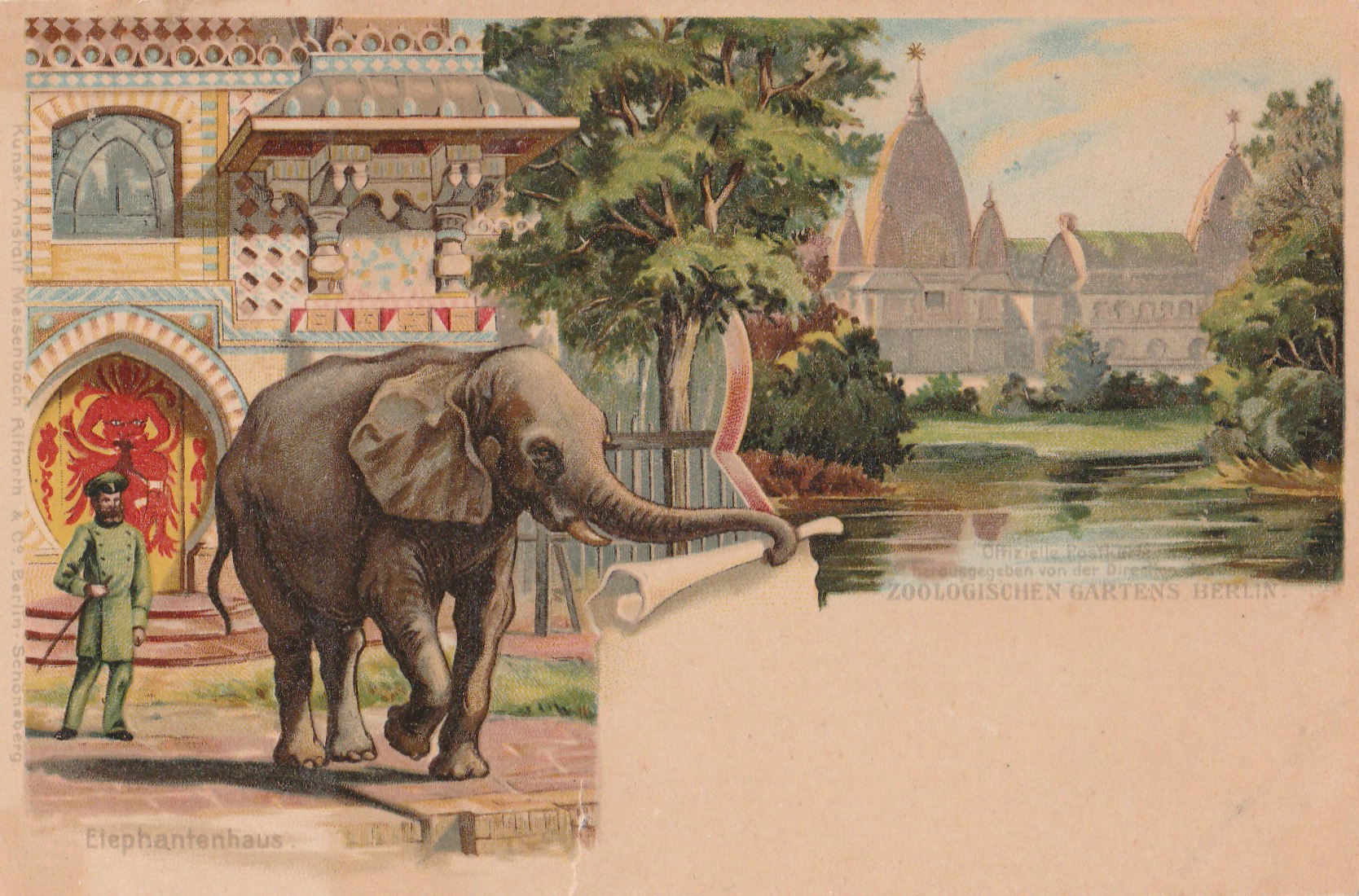

Also serving the purpose of entertainment was the exoticising zoo architecture, which had increasingly become a mainstay of many European zoos since the 1850s. These stylised structures formed the backdrop for the animals – and still do today. The first major exoticizing architectural project in Berlin was the antelope and giraffe house, which was built in a so-called ‘Moorish’ style. It was followed by what was referred to as the Elephant Pagoda, which emulated an Indian-style temple, and the ostrich house, built in the style of an ancient Egyptian temple. They conveyed stereotypical images of regions foreign to Europeans and sometimes bore no relation whatsoever to the animals on display. For example, in the Indian pagoda, Indian and African rhinoceroses and elephants were shown side by side, and Australian ostriches were exhibited in the Egyptian temple.

The antelope house at Berlin Zoo, around 1920. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Postcard of the Elephant Pagoda at Berlin Zoo, 1912. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

For the historian Christina Wessely, these buildings were “situated almost ideally at the intersection of entertainment and popular scientific education”.11

In 2019, 3.5 million visitors visited Berlin Zoo. The vast majority of them did not live in Berlin or Germany. Berlin Zoo, its animals, and its architecture, are very clearly part of Berlin’s tourist infrastructure. The zoo generates its income as a leisure facility. However, in order to legitimise a facility that keeps animals in human captivity and puts them on display, the zoo has long done away with its emphasis on recreation, which was a central factor for over 150 years. In contrast, the zoo as a space of learning was playing a more important role in the zoo’s communications and self-understanding by the end of the 19th century at the latest.

Education: Show Animals and Collecting Practices

In the 19th century, zoos’ exoticizing architecture was often accompanied by very small stalls. Even though his plan never materialised, zoo director Ludwig Heck (in office from 1888 to 1932) had the goal, at least in theory, of presenting the complete fauna of the world. From a contemporary perspective, the systematic or  taxonomically ordered zoo, with its (often lone) specimens of individual species from various geographical regions exhibited next to each other, provided neither the

taxonomically ordered zoo, with its (often lone) specimens of individual species from various geographical regions exhibited next to each other, provided neither the  social animals nor the public with any advantages. The small stalls, of course, did not allow the animals to live out their natural behaviour. The antelope house, built in 1872 with 20 cages arranged in an oval shape, the deer park, which had over 60 enclosures around 1900, and the aviary, opened in 1895, were examples of this collecting practice, whose aspirations to completeness prevailed over ensuring that the animals were kept in suitable conditions. In the aviary, cages were arranged one on top of the other in three storeys.12 Despite their exoticizing backdrop, these enclosures were like department stores. However, their collections “suggested that the world was comprehensible”, without “any gaps, any incompleteness”.13 As they passed through, visitors were supposed to identify the similarities and differences, thereby participating in the

social animals nor the public with any advantages. The small stalls, of course, did not allow the animals to live out their natural behaviour. The antelope house, built in 1872 with 20 cages arranged in an oval shape, the deer park, which had over 60 enclosures around 1900, and the aviary, opened in 1895, were examples of this collecting practice, whose aspirations to completeness prevailed over ensuring that the animals were kept in suitable conditions. In the aviary, cages were arranged one on top of the other in three storeys.12 Despite their exoticizing backdrop, these enclosures were like department stores. However, their collections “suggested that the world was comprehensible”, without “any gaps, any incompleteness”.13 As they passed through, visitors were supposed to identify the similarities and differences, thereby participating in the  order themselves.

order themselves.

The inside of the aviary at Berlin Zoo, around 1930. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

However, their  labels often said very little, mirroring the lack of space available to the animals. Visitors often did not learn anything apart from the species’ Latin names. There was no information about their habitats or diets. The goal of educating visitors about natural history had been addressed in the first founding documents of Berlin Zoo, as we have seen. However, for about 100 years, the idea of ‘education’ was exclusively limited to the zoo’s taxonomic architecture and reduced entry for the city’s school pupils. It was expected of them and their teachers that they would passively take advantage of what was on offer in the exhibition and make their own observations based on their prior knowledge.

labels often said very little, mirroring the lack of space available to the animals. Visitors often did not learn anything apart from the species’ Latin names. There was no information about their habitats or diets. The goal of educating visitors about natural history had been addressed in the first founding documents of Berlin Zoo, as we have seen. However, for about 100 years, the idea of ‘education’ was exclusively limited to the zoo’s taxonomic architecture and reduced entry for the city’s school pupils. It was expected of them and their teachers that they would passively take advantage of what was on offer in the exhibition and make their own observations based on their prior knowledge.

It was only in 1972 that education became the focus of one of the conferences organised by the International Union of Directors of Zoological Gardens, which had been founded in 1935.14 Interestingly, the zoos of the GDR were more committed to active education in zoological gardens. At both Dresden Zoo and Tierpark Berlin, zoo schools had been opened as far back as in the early 1960s. They were facilities that provided systematic educational offers to visiting school pupils in the form of guided tours and natural history lessons. In 1968, Rostock Zoo organised a conference on the topic. Even though a zoo school had been opened in Frankfurt am Main at the urging of Bernhard Grzimek in 1960, no such school was opened in West Berlin until 1985.15 Perhaps the entrenchment of the GDR’s zoological gardens within the cultural administration and their incorporation into the socialist educational ideal were the reasons for the earlier introduction of learning formats for natural history knowledge.

In 2019, the zoo school carried out 2,997 guided tours with over 34,700 visitors (of whom 23,301 were children). That same year, Tierpark Berlin put on a total of 2,027 guided tours for 14,096 children and 8,184 adults.16

Research: but for which Habitat?

In the early decades of most of the zoos founded in the second half of the 18th century, the focus – at least in the eyes of zoo management – was on the scientific value of animal collections. Zoos were places where it was possible to  classify and draw up

classify and draw up  inventories of the animal world, where it was possible not just to show the world’s fauna but also to comprehend it for the first time. Animals from all over the world were being kept for the first time at Berlin Zoo and, after their deaths, were described as species for the first time by the Natural History Museum.17 Museum curator Paul Matschie, for example, described the East African civet by comparing a zoo animal with a museum taxidermy. The

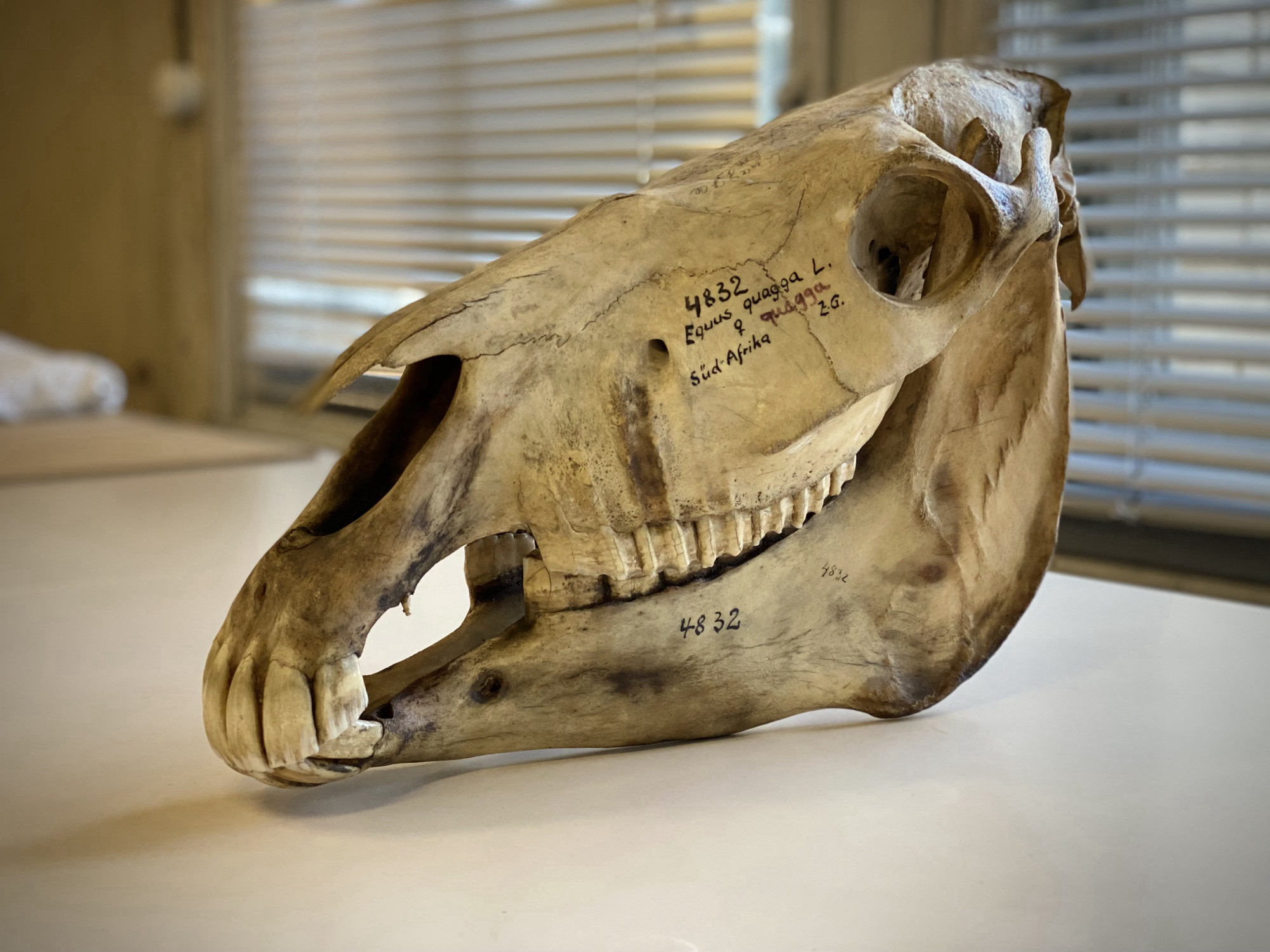

inventories of the animal world, where it was possible not just to show the world’s fauna but also to comprehend it for the first time. Animals from all over the world were being kept for the first time at Berlin Zoo and, after their deaths, were described as species for the first time by the Natural History Museum.17 Museum curator Paul Matschie, for example, described the East African civet by comparing a zoo animal with a museum taxidermy. The  last specimens of the quagga, the thylacine, and the Schomburgk’s deer living at the zoo became type specimens at the Natural History Museum.18

last specimens of the quagga, the thylacine, and the Schomburgk’s deer living at the zoo became type specimens at the Natural History Museum.18

Quagga skull at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, 2020. (Image: Clemens Maier-Wolthausen/MfN. All rights reserved.)

This more or less anatomical, comparative research into zoo animals was followed by a phase in which the emphasis was placed on making observations of animal behaviour. By observing the behaviour of zoo animals, researchers developed the first approaches of what would later be called behavioural science. In early 20th-century Berlin,  Oskar Heinroth, director of the Berlin Aquarium from 1913, was researching Europe’s avifauna and carrying out his first studies in what he referred to as animal psychology (ethology), together with

Oskar Heinroth, director of the Berlin Aquarium from 1913, was researching Europe’s avifauna and carrying out his first studies in what he referred to as animal psychology (ethology), together with  Magdalena Heinroth and later

Magdalena Heinroth and later  Katharina Heinroth.19 However, Berlin Zoo often only invested limited or no capacities at all into research. It benefited from the reputations of scientists at academic institutions who came to the zoo and examined the objects on show. Researchers like the Heinroths remained the exception.

Katharina Heinroth.19 However, Berlin Zoo often only invested limited or no capacities at all into research. It benefited from the reputations of scientists at academic institutions who came to the zoo and examined the objects on show. Researchers like the Heinroths remained the exception.

As zoo director (from 1945), Katharina Heinroth published a huge number of articles; however, much like those by her colleague Heinrich Dathe at East Berlin’s Tierpark, many of them dealt with observations and reports on the  practice of zookeeping. Zoos are still conducting research, but most of it is research into the veterinary medicine areas of zookeeping. It focuses on stem cell generation, assisted reproduction,

practice of zookeeping. Zoos are still conducting research, but most of it is research into the veterinary medicine areas of zookeeping. It focuses on stem cell generation, assisted reproduction,  feeding methods , and feed,20 which are usually part of the scientific branch of zoo biology. This is scientific research – conducted in zoos – where the object of study is the animal held in human captivity.21 However, fundamental insights are still being gained – such as the gestation periods for various animals or embryonic diapause in bears – that also enrich our knowledge of wildlife overall.

feeding methods , and feed,20 which are usually part of the scientific branch of zoo biology. This is scientific research – conducted in zoos – where the object of study is the animal held in human captivity.21 However, fundamental insights are still being gained – such as the gestation periods for various animals or embryonic diapause in bears – that also enrich our knowledge of wildlife overall.

In the GDR, zoos were explicitly expected to continuously produce and publish research. The ‘Research Plan of the Zoological Gardens of the GDR for the Planning Period 1976-1980’ predominantly lists research projects related to zookeeping. The Ministry of Culture suspected that scientists only planned studies on the ethology and biology of wild species in order to generate travel opportunities.22

Now let us come to the final point on Hediger’s list: nature or wildlife conservation. This purpose is also the youngest chronologically speaking.

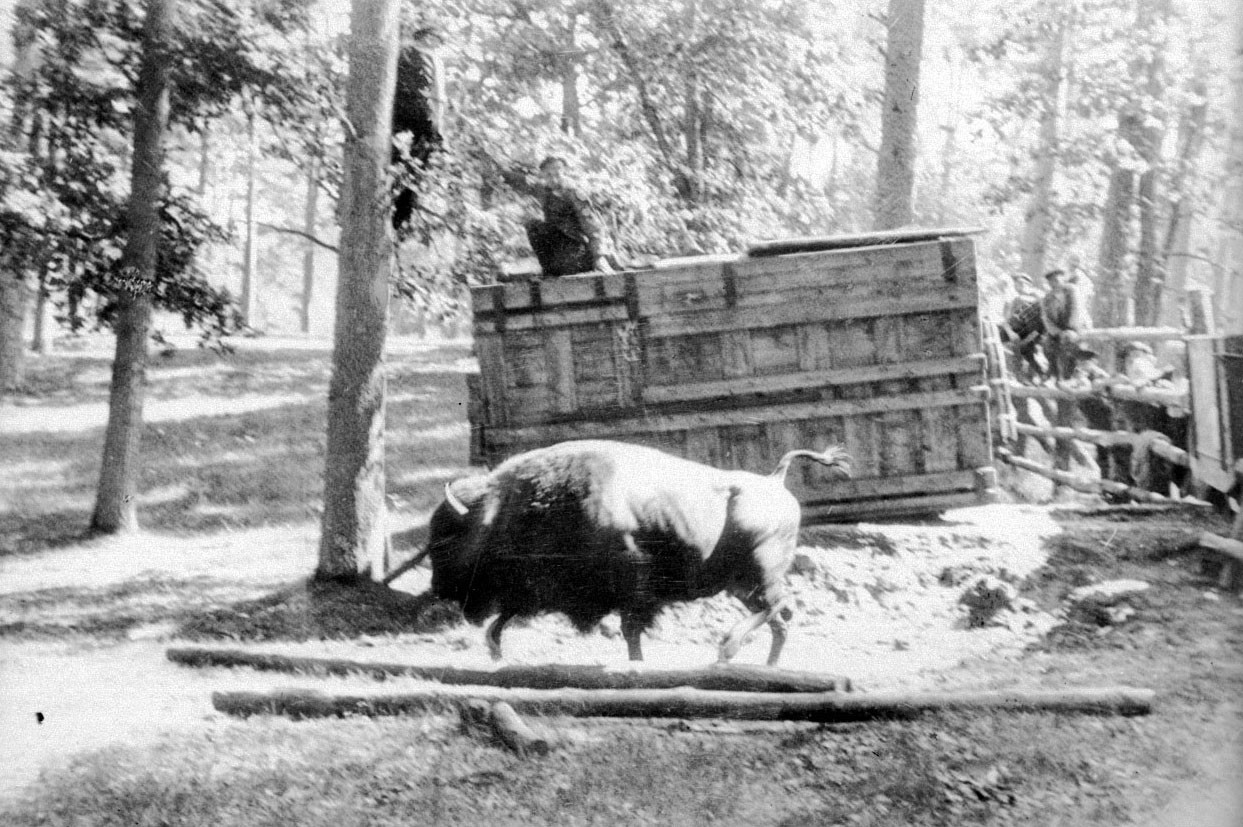

Wildlife Conservation: Adjustments and Objectives

As previously mentioned, the Bronx Zoo was founded in 1899 to breed endangered American animals, but soon transformed into a leisure facility.23 For a long time, it was rare to find animals bred in captivity, and in Berlin they were viewed as achievements of zookeeping or as affordable enrichments to the animal collection. In 1923, Europe’s zoos then founded the first breeders’ community in the form of the Society for the Preservation of the Wisent. And the wisent breed registry did in fact make it possible to protect this species from  extinction. In the 1960s, more such breed registries were introduced in North America and Europe.

extinction. In the 1960s, more such breed registries were introduced in North America and Europe.

Reintroduction of a bison, probably at the Schorfheide Game Reserve, around 1930. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

While for Hediger breeding to preserve a species was just one of four reasons for running a zoo, a paper given by the director of the Rotterdam Zoo, Dick van Dam, at the 1980 conference of the International Union of Directors of Zoological Gardens put the exhibition and breeding of endangered species at the forefront of future zoo strategies for the first time. In his paper, “The Future of Zoological Gardens”, van Dam explained that the breeding of endangered species in human captivity had to become one of zoos’ central purposes. He viewed the financial and legal difficulties of  procuring new animals imposed by the 1973 Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora as the most important reason for doing so. In his reading, breeding animals in zoos would ensure that the zoos’ own collections maintained their appeal.24 In 1993, the director of Cologne Zoo also claimed that the Washington Convention was the reason that zoos were being forced to become ‘self-suppliers’ when it came to visually appealing but endangered animals.25 And in fact, from the late 1980s on, the significance attributed by zoos to wildlife conservation in their self-understandings but also in their external communications increased. In 1994, a book was published to mark the anniversary of Berlin Zoo with the title Noah’s Ark on the Spree.

procuring new animals imposed by the 1973 Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora as the most important reason for doing so. In his reading, breeding animals in zoos would ensure that the zoos’ own collections maintained their appeal.24 In 1993, the director of Cologne Zoo also claimed that the Washington Convention was the reason that zoos were being forced to become ‘self-suppliers’ when it came to visually appealing but endangered animals.25 And in fact, from the late 1980s on, the significance attributed by zoos to wildlife conservation in their self-understandings but also in their external communications increased. In 1994, a book was published to mark the anniversary of Berlin Zoo with the title Noah’s Ark on the Spree.

Heinz-Georg Klös Noah’s Ark on the Spree, Berlin: FAB Verlag, 1994.

One way to convey the topic of wildlife conservation and habitat protection in zoological gardens to a broad public is to draw on  ‘animals with appeal’, i.e., animals that attract large crowds. Their enclosures are places where large groups of people can be addressed. These animals generally include the pachyderms, the big cats, and the

‘animals with appeal’, i.e., animals that attract large crowds. Their enclosures are places where large groups of people can be addressed. These animals generally include the pachyderms, the big cats, and the  ‘cute’ animals.26 The hope is that interest in these animals, together with the associated information, will stir visitors’ interest in their habitats and their conservation. Moreover, the idea is that these animals will generate the income that will make it possible to show less appealing but more endangered species. From the perspective of zoos, the flagship species are ideal in this regard. In zoo biology, these are endangered species with high appeal, and protecting them makes it possible to protect many other animal species that share a habitat with them.27 Zoo critics, however, point out that, in terms of numbers, there have been few successful

‘cute’ animals.26 The hope is that interest in these animals, together with the associated information, will stir visitors’ interest in their habitats and their conservation. Moreover, the idea is that these animals will generate the income that will make it possible to show less appealing but more endangered species. From the perspective of zoos, the flagship species are ideal in this regard. In zoo biology, these are endangered species with high appeal, and protecting them makes it possible to protect many other animal species that share a habitat with them.27 Zoo critics, however, point out that, in terms of numbers, there have been few successful  reintroductions of zoo animals to the wild and that, in their opinion, zoos are putting only small sums into local wildlife conservation programmes. They also doubt that zoos’ educational offerings about endangered animals have any real effect on visitors.28 Institutions like the German Species Protection Foundation (Stiftung Artenschutz), which is funded by Germany’s zoological gardens, refute this and point to their successes.

reintroductions of zoo animals to the wild and that, in their opinion, zoos are putting only small sums into local wildlife conservation programmes. They also doubt that zoos’ educational offerings about endangered animals have any real effect on visitors.28 Institutions like the German Species Protection Foundation (Stiftung Artenschutz), which is funded by Germany’s zoological gardens, refute this and point to their successes.

In 1999, the European Union passed a zoo directive.29 Significantly, it no longer mentions recreation as one of the purposes of a zoo, only education and wildlife conservation research, which also includes captive breeding. Although the world conservation strategy of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) mentions zoos as spaces of recreation, it focuses almost exclusively on their role as centres for nature and wildlife conservation.30 Today, in light of species extinctions, the more than 300 zoos that make up the WAZA describe themselves as centres for wildlife conservation. The only goals for zoos named in the organisation’s constitution, passed in 2010, are: environmental education, wildlife conservation, and environmental research.31

The strategic communications of zoos are increasingly focusing on wildlife conservation. This is having an impact on visitors. A Forsa study commissioned by the German Association of Zoological Gardens in 2020 entitled “The Germans and their Zoos” found that the population generally approves of zoological gardens.32 In response to the question about the purpose of a zoo, the idea of the zoo as a space of recreation, which had been around since the earliest days of zoo history, was not presented as an option. Instead, most of those surveyed said that preserving biological diversity by keeping and breeding endangered species was an especially important task for zoos – a task that, at least in Berlin, played a role during the founding of neither Berlin Zoo nor Tierpark Berlin.

Showing Animals: Continuities and Shifts

Putting animals on display still forms the  basic livelihood of all zoological gardens worldwide. As can be seen by looking at institutions like Berlin Zoo, the reasons and justifications for showing animals like this have fluctuated and shifted over time. A wide range of different aspects have been at the forefront of guests’ and zoos’ interests, and corporate communication as well. The reason for this is the different functions that putting animals on display has fulfilled at various points in time. There have frequently been discrepancies between the ideas held by zoo management and visitors as to why animals should be shown. The latter have demanded the ‘entertainment factor’ as something that is at least equal with other aspects. The management of Berlin Zoo clearly favoured other purposes at the beginning, but as a joint-stock company, it was forced to meet this wish.33

basic livelihood of all zoological gardens worldwide. As can be seen by looking at institutions like Berlin Zoo, the reasons and justifications for showing animals like this have fluctuated and shifted over time. A wide range of different aspects have been at the forefront of guests’ and zoos’ interests, and corporate communication as well. The reason for this is the different functions that putting animals on display has fulfilled at various points in time. There have frequently been discrepancies between the ideas held by zoo management and visitors as to why animals should be shown. The latter have demanded the ‘entertainment factor’ as something that is at least equal with other aspects. The management of Berlin Zoo clearly favoured other purposes at the beginning, but as a joint-stock company, it was forced to meet this wish.33

At a time when visual media are making it possible to access the lives of wild animals on a previously unseen scale but are also constantly pointing to their endangerment, questions about the reasons for putting live animals on display are still or again being raised. Media discourse is often more critical of zoos than the still very high visitor numbers in German zoos might lead us to believe. In 2009, about five million people visited Berlin’s zoological gardens – a record in terms of visitor numbers – which is testament to the sustained popularity of the zoo as an institution. There is certainly a connection between the changing communications of the zoological gardens about their goals and tasks and the emphasis on wildlife conservation and habitat protection, which currently seems to be addressing the needs of visitors and zoos for legitimacy. However, zoological gardens have to keep renegotiating how this task can be performed by putting animals on display. If they don’t, they will prove anthropologists like Volker Sommer right:

“The only suitable central marker of identity for zoos is Hediger’s pillar of ‘recreation’. Because this parameter addresses human interests, zoos will remain what they have always been: entertainment facilities where wild animals – as the German Federal Conservation Act states rather dryly – are locked up ‘for the purpose of putting them on display’.”34

- For an introduction to the history of zookeeping see Vernon N. Kisling. “Ancient Collections and Menageries”. In Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections to Zoological Gardens, Vernon N. Kisling (ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2001: 1-47.↩

- Elizabeth Hanson. Animal Attractions: Nature on Display in American Zoos. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2002: 46; see also Wilfrid Blunt. The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1976: 25.↩

- Quoted in Heinz-Georg Klös. Von der Menagerie zum Tierparadies: 125 Jahre Zoo Berlin. Berlin: Haude & Spenersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1969: 28.↩

- Copy of the charter of the Actien-Vereins des Zoologischen Gartens zu Berlin (version dated 14 May 1869), collection of the Archive of Berlin‘s Zoological Gardens.↩

- Peter Dollinger and Verband Deutscher Zoodirektoren (eds.). Gärten für Tiere: Erlebnisse für Menschen: Die Zoologischen Gärten des VDZ, 125 Jahre Verband Deutscher Zoodirektoren e.V., 1st ed. Cologne: Bachem, 2012: 19.↩

- Heini Hediger. “Bedeutung und Aufgaben der Zoologischen Gärten”. Vierteljahresschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich 18 (1973): 319-328, 327.↩

- Christina Wessely. Künstliche Tiere: Zoologische Gärten und urbane Moderne. Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2008: 38.↩

- Eric Baratay. “Theater des ‘Wilden’: Zoologische Gärten in der Zeit August Gauls”. In August Gaul: Moderne Tiere, K. Lee Chichester, Nina Zimmer, and Kunstmuseum Bern (eds.). Munich: Hirmer, 2021: 45-58, 49.↩

- Ursula Klös, Harro Strehlow, and Werner Synakiewicz. Der Berliner Zoo im Spiegel seiner Bauten, 1841-1989: Eine baugeschichtliche und denkmalpflegerische Dokumentation über den Zoologischen Garten Berlin. Heinz-Georg Klös and Ursula Klös (eds.). 2nd ed. Berlin: Heenemann, 1990, 171ff.↩

- Fedor von Zobeltitz. “Wie man im Zoologischen Garten isst und trinkt”. Moderne Kunst XVIII, no. 2 (um 1900): 5-8.↩

- Wessely, 2008: 100, 102.↩

- Klös, Strehlow, Synakiewicz. 1990: 95; see also Clemens Maier-Wolthausen. Hauptstadt der Tiere: Die Geschichte des ältesten deutschen Zoos, Andreas Knieriem (ed.). Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2019: 52.↩

- Wessely, 2008: 90, 105.↩

- Laura Penn, Markus Gusset, and Gerald Dick. 77 Years: The History and Evolution of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, 1935-2012, World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (ed.). Gland: World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA), 2012: 144.↩

- Zoologischer Garten Rostock: Voreinladung, Januar 1969, AZGB, O 1/2/185; Mustafa Haikal and Winfried Gensch. Der Gesang des Orang-Utans: Die Geschichte des Dresdner Zoos. Dresden: Ed. Sächs. Zeitung, 2011: 109; Heinz-Georg Klös, Hans Frädrich, and Ursula Klös. Die Arche Noah an der Spree: 150 Jahre Zoologischer Garten Berlin, Eine tiergärtnerische Kulturgeschichte von 1844-1994. Berlin: FAB Verlag, 1994: 415; Lothar Dittrich. “Menschen im Zoo”. In Berichte aus der Arche. Dieter Poley (ed.). Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag, 1993: 140; Robert Pies-Schulz-Hofen. “Die Berliner Zooschule”. Bongo 12 (1987): 59-66.↩

- Zoologischer Garten Berlin AG and Tierpark Berlin-Friedrichsfelde GmbH. Geschäftsbericht 2019. Berlin: 2020: 22, 116.↩

- Ludwig Heck, Heiter-ernste Lebensbeichte: Erinnerungen eines alten Tiergärtners. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag, 1938.↩

- Renate Angermann. “Anna Held, Paul Matschie und die Säugetiere des Berliner Zoologischen Gartens”. Bongo 24 (1994): 107-138; Joachim Oppermann. “Tod und Wiedergeburt: Über das Schicksal berühmter Berliner Zootiere”. Bongo 24 (1994): 51-84.↩

- Cf. Karl Schulze-Hagen. Die Vogel-WG: Die Heinroths, ihre 1000 Vögel und die Anfänge der Verhaltensforschung. Munich: Knesebeck, 2020.↩

- Examples of institutionalised research into zoo animals can be found in Berlin at the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research and in Frankfurt at the Endowed Professorship of Zoo Biology at the Faculty of Biological Sciences at Goethe University. The former can trace its origins back to a faculty of the GDR‘s Academy of Sciences and was always located on the premises of Berlin Tierpark; the latter was launched by the Opel Hessische Zoostiftung in 2014.↩

- Heini Hediger. Mensch und Tier im Zoo: Tiergarten-Biologie. Rüschlikon-Zurich: Albert Müller, 1965: 62.↩

- The research plan and correspondence with the GDR Ministry of Culture can be found in: German Federal Archives Berlin-Lichterfelde, DR 1/5700.↩

- Hanson, 2002: 46; see also Blunt, 1976: 25.↩

- Penn, Gusset, Dick. 2012: 168; see also Dick van Dam. “The Future of Zoological Gardens”. IUDZG, Minutes and Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference Held from 13-18 October 1980 (AZGB, V 5/64).↩

- Gunter Nogge. “Arche Zoo: Vom Tierfang zum Erhaltungszuchtprogramm”. In Berichte aus der Arche. Dieter Poley (ed.). Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag, 1993: 80.↩

- Meier, Jürg. Handbuch Zoo: Moderne Tiergartenbiologie. 1st ed. Bern: Haupt Verlag, 2009: 115-120.↩

- Stefan Hübner. “‘Die afrikanischen Elefanten sind unser Flaggschiff’: Thomas Kauffels erzählt von der Geschichte des Opel-Zoos”. Hessischer Rundfunk, 03.02.2021. https://www.hr2.de/podcasts/doppelkopf/die-afrikanischen-elefanten-sind-unser-flaggschiff--thomas-kauffels-erzaehlt-von-der-geschichte-des-opel-zoos,podcast-episode-82032.html (16.08.2021). For a definition of flagship species see Meier, 2009: 121.↩

- See for example Volker Sommer. “Ein Etikettenschwindel”. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 71, no. 9 (2021): 35-38; Bob Mullan and Garry Marvin. Zoo Culture, 2nd ed. Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999; or Hilal Sezgin. Artgerecht ist nur die Freiheit: Eine Ethik für Tiere oder warum wir umdenken müssen. Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck, 2014.↩

- “Council Directive 1999/22/EC of 29 March 1999 relating to the keeping of wild animals in zoos”. Official Journal of the European Communities, 09.04.1999. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:1999:094:0024:0026:EN:PDF (01.09.2021).↩

- Verband Deutscher Zoodirektoren e.V. “Wer Tiere kennt, wird sie schützen: Die Welt-Zoo-Naturschutzstrategie im deutschsprachigen Raum”. WAZA, 2006. https://www.waza.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/marketing_brochure_german.pdf (27.08.2021); see also World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. “Building a Future for Wildlife: The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Strategy”. WAZA, 2005. https://www.waza.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/wzacs-en.pdf (01.09.2021).↩

- Penn, Gusset, Dick. 2012: 168.↩

- Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. “Die Deutschen und ihre Zoos: Ergebnisse der Forsa Studie”. VDZ, 2020. https://www.vdz-zoos.org/fileadmin/PMs/2020/VdZ/Forsa-Broschuere_Die_Deutschen_und_ihre_Zoos.pdf (27.08.2021).↩

- Wessely, 2008: 37.↩

- Sommer, 2021: 38.↩