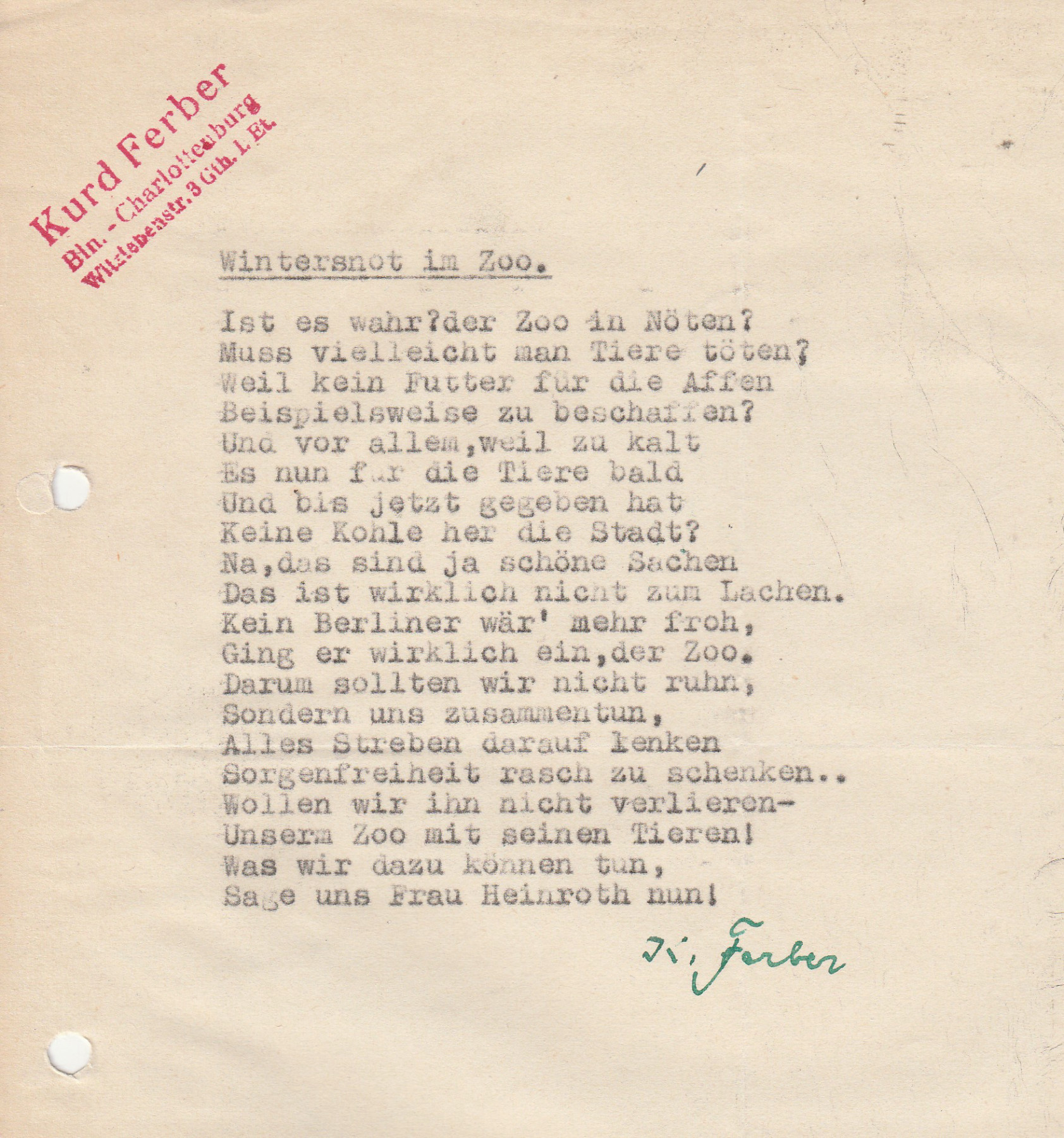

Poem by zoo visitor K. Ferber about the winter food crisis in the zoo, see  Winter Hardship at the Zoo 06.10.1948. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Winter Hardship at the Zoo 06.10.1948. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

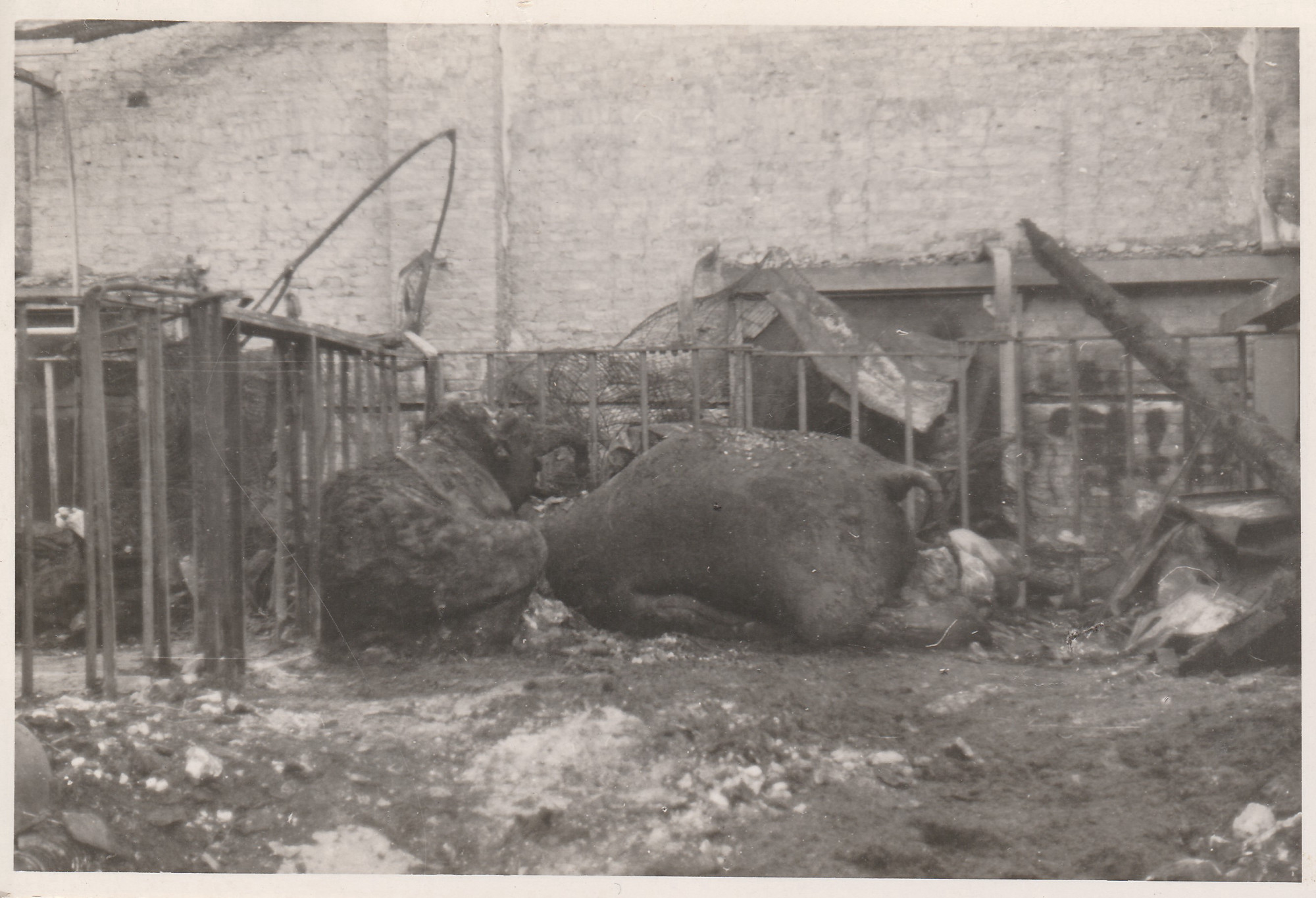

At the end of the Second World War, there were only about 80 animals left in the Berlin Zoological Garden. In  1938, there had been over 3,000, and even in 1944, there had still been as many as 1,700.1 By May 1945, much of the zoo, including the Elephant Pagoda, had been destroyed.

1938, there had been over 3,000, and even in 1944, there had still been as many as 1,700.1 By May 1945, much of the zoo, including the Elephant Pagoda, had been destroyed.

Elephant carcass at Berlin Zoo after a bombing raid in 1943. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

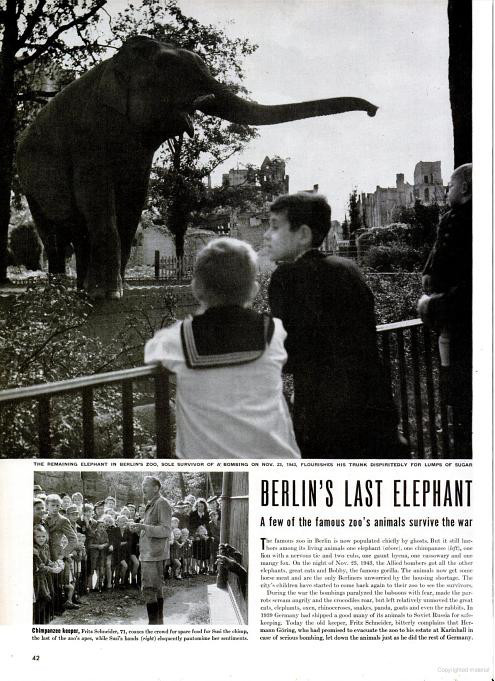

The Asian elephant bull “Siam” was one of the few surviving animals. He had actually been brought to Germany from the British colony of Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, as a so-called  wild catch, to join the Krone Circus. However, when “Siam” showed behavioral problems, the circus sought a way to get rid of what was labelled a ‘bad’ animal, and gave “Siam” to Berlin Zoo in 1933. He was the only one of Berlin Zoo’s nine elephants to survive the war. Seven had been killed in the bombing raids of

wild catch, to join the Krone Circus. However, when “Siam” showed behavioral problems, the circus sought a way to get rid of what was labelled a ‘bad’ animal, and gave “Siam” to Berlin Zoo in 1933. He was the only one of Berlin Zoo’s nine elephants to survive the war. Seven had been killed in the bombing raids of  November 1943.

November 1943.

Life Magazine reported on Berlin Zoo’s only surviving elephant after the war, October 1945.

At the time, the zoo was suffering from a lack of everything, from feed to firewood to building materials. With few employees and almost no financial means, zoologist  Katharina Heinroth, who also officially became director of the war-ravaged zoological garden on 3 August 1945, had great difficulty keeping the remaining animals alive. In as early as May, the Soviet commander (Berlin was occupied and administered by Soviet troops at the time) had issued permission for the buying of feed, so that the zoo could, for the time being, purchase meat for the carnivores as well as hay, oats, and potatoes.2 Nevertheless, the situation was tense and procuring feed remained a burning issue for the next few years. Writing about the food situation in March 1946, Katharina Heinroth said: “The scarcity of feed is terrible; potatoes, beets, hay, and straw are what we lack most. […] We haven’t had any potatoes in four months.”3 How was she supposed to feed an elephant in these conditions?

Katharina Heinroth, who also officially became director of the war-ravaged zoological garden on 3 August 1945, had great difficulty keeping the remaining animals alive. In as early as May, the Soviet commander (Berlin was occupied and administered by Soviet troops at the time) had issued permission for the buying of feed, so that the zoo could, for the time being, purchase meat for the carnivores as well as hay, oats, and potatoes.2 Nevertheless, the situation was tense and procuring feed remained a burning issue for the next few years. Writing about the food situation in March 1946, Katharina Heinroth said: “The scarcity of feed is terrible; potatoes, beets, hay, and straw are what we lack most. […] We haven’t had any potatoes in four months.”3 How was she supposed to feed an elephant in these conditions?

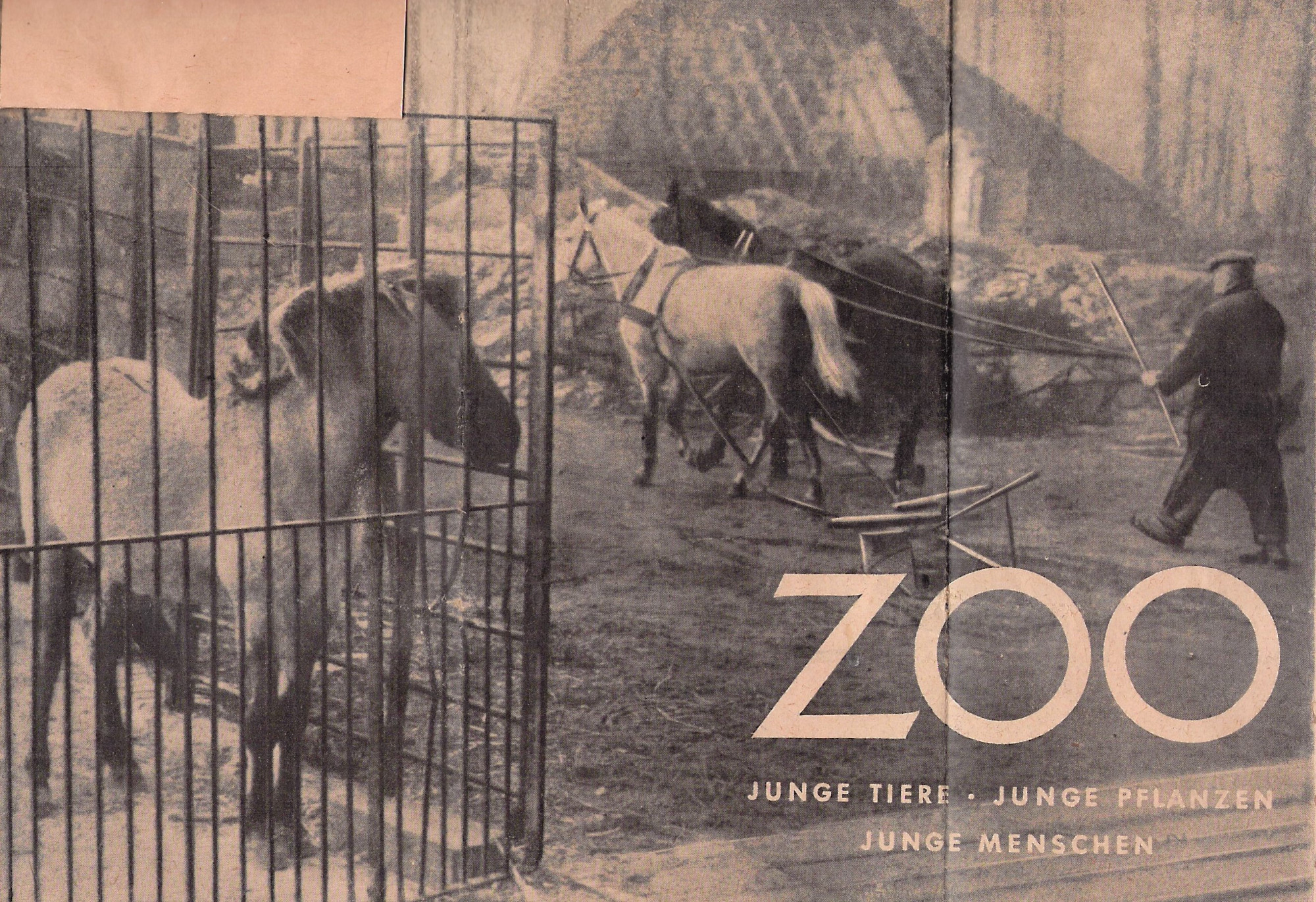

After the biggest pieces of rubble had been cleared, Katharina Heinroth and the zoo staff set about producing feed for the animals themselves. Heinroth’s initial ambition when she reopened the zoo in July 1945 had been to offer a place that gave people an opportunity for rest and recreation beyond the daily postwar routine. “I also dreamed of beautiful flowerbeds in the avenues”, said Katharina Heinroth in an interview, “but things have turned out differently. Every free corner has to be used for planting vegetables. The empty outdoor enclosures that are left have been divided among the staff for personal use”.4 Apart from the nursery, whose beds were already full of plants, “all the open space throughout the zoo, created by the war, was now to be used to grow animal feed”.5 The deer enclosure became a vegetable patch; beets, potatoes, and lettuce were soon growing on the open lawns and in the elephant enclosure.6 In short: the zoo was being plowed.

Vegetable and lettuce cultivation on the grounds of the Berlin Zoological Garden, reprinted in Vorwärts, 18.04.1946.

The illustrated magazine Die Frau von heute reports on the growing of vegetables and lettuce in the Berlin Zoological Garden, 07.05.1946.

However, these crops were not nearly enough to feed even the small number of herbivores the zoo had, and, as mentioned above, the animals also had to share what there was with the zoo’s staff.7 The zoo therefore rented additional plots on the outskirts of Berlin – “expanses of land against which the few small gardens in the enclosures pale in comparison”.8 In Spandauer Forst and Grunewald, for example, they sowed nine hectares with green fodder and grass for making hay. But “even this is no more than supplementary feed”,9 Katharina Heinroth wrote in reply to a letter from a zoo visitor. The feed shortage directly impacted any efforts to restore the zoo’s  animal population. Increasing the population at all, let alone procuring more large mammals from the other side of the world, was out of the question for the time being. In the summer of 1947, therefore, Heinroth still had to reply to letters from Berliners asking for a new herd of elephants: “Unfortunately, it will not be possible to acquire another herd of elephants in the next few years, as the difficulties with food supply in the city are far too great. At the moment we only have our old elephant “Siam” and we have our hands full trying to get him enough hay and straw, grass and turnips.”10

animal population. Increasing the population at all, let alone procuring more large mammals from the other side of the world, was out of the question for the time being. In the summer of 1947, therefore, Heinroth still had to reply to letters from Berliners asking for a new herd of elephants: “Unfortunately, it will not be possible to acquire another herd of elephants in the next few years, as the difficulties with food supply in the city are far too great. At the moment we only have our old elephant “Siam” and we have our hands full trying to get him enough hay and straw, grass and turnips.”10

Though, just ten years later, the death of animals due to  overfeeding by visitors led to a general

overfeeding by visitors led to a general  ban on feeding at the Berlin Zoo, things were quite different in the late 1940s. The efforts of the zoo staff alone were not enough to provide for the animals. The zoo was dependent on the city: on its transport infrastructure, slaughterhouses, and governing authorities, as well as on zoogoers. In newspaper articles, Katharina Heinroth called on the people of Berlin to support the animals by donating food.

ban on feeding at the Berlin Zoo, things were quite different in the late 1940s. The efforts of the zoo staff alone were not enough to provide for the animals. The zoo was dependent on the city: on its transport infrastructure, slaughterhouses, and governing authorities, as well as on zoogoers. In newspaper articles, Katharina Heinroth called on the people of Berlin to support the animals by donating food.

Appeal to save the zoo printed in the Illustrated Telegraph, March 1949.

Even if Berliners did not manage to “give the zoo immediate peace of mind”, as a visitor’s poem about the  winter hardship at the zoo puts it, people did donate food stamps, bring old bread and potato peelings, and collect acorns for the animals. Katharina Heinroth is quoted as saying, “‘Siam’ consumes whole baskets of them and most of the other animals also seem to be quite satisfied with this substitute.”11 Visitors to German zoos were generally allowed to feed the animals, albeit with some restrictions, well into the 1950s. In times of food scarcity, Heinroth even increasingly used newspaper articles to appeal to people to collect, bring, and donate food. Whereas in the past feeding the animals tended to be something we tolerated, “nowadays we would be grateful if more visitors engaged in this pleasure”, writes the Neue Zeitung in 1949.12 The illustrated women’s magazine Die Frau von heute, published from 1946 as the mouthpiece of the municipal women’s committees of the Soviet Occupation Zone,13 also encouraged its readers to get involved informing them that all zoo animals “are very receptive to vegetable scraps, carrots, and the like. And anyone who has any potato peelings will always find grateful takers at the zoo!”14 The zoo made

winter hardship at the zoo puts it, people did donate food stamps, bring old bread and potato peelings, and collect acorns for the animals. Katharina Heinroth is quoted as saying, “‘Siam’ consumes whole baskets of them and most of the other animals also seem to be quite satisfied with this substitute.”11 Visitors to German zoos were generally allowed to feed the animals, albeit with some restrictions, well into the 1950s. In times of food scarcity, Heinroth even increasingly used newspaper articles to appeal to people to collect, bring, and donate food. Whereas in the past feeding the animals tended to be something we tolerated, “nowadays we would be grateful if more visitors engaged in this pleasure”, writes the Neue Zeitung in 1949.12 The illustrated women’s magazine Die Frau von heute, published from 1946 as the mouthpiece of the municipal women’s committees of the Soviet Occupation Zone,13 also encouraged its readers to get involved informing them that all zoo animals “are very receptive to vegetable scraps, carrots, and the like. And anyone who has any potato peelings will always find grateful takers at the zoo!”14 The zoo made  use of leftovers from the city’s provisions that were not (or no longer) suitable for human consumption, from canteen leftovers to potato peelings from private households.15

use of leftovers from the city’s provisions that were not (or no longer) suitable for human consumption, from canteen leftovers to potato peelings from private households.15

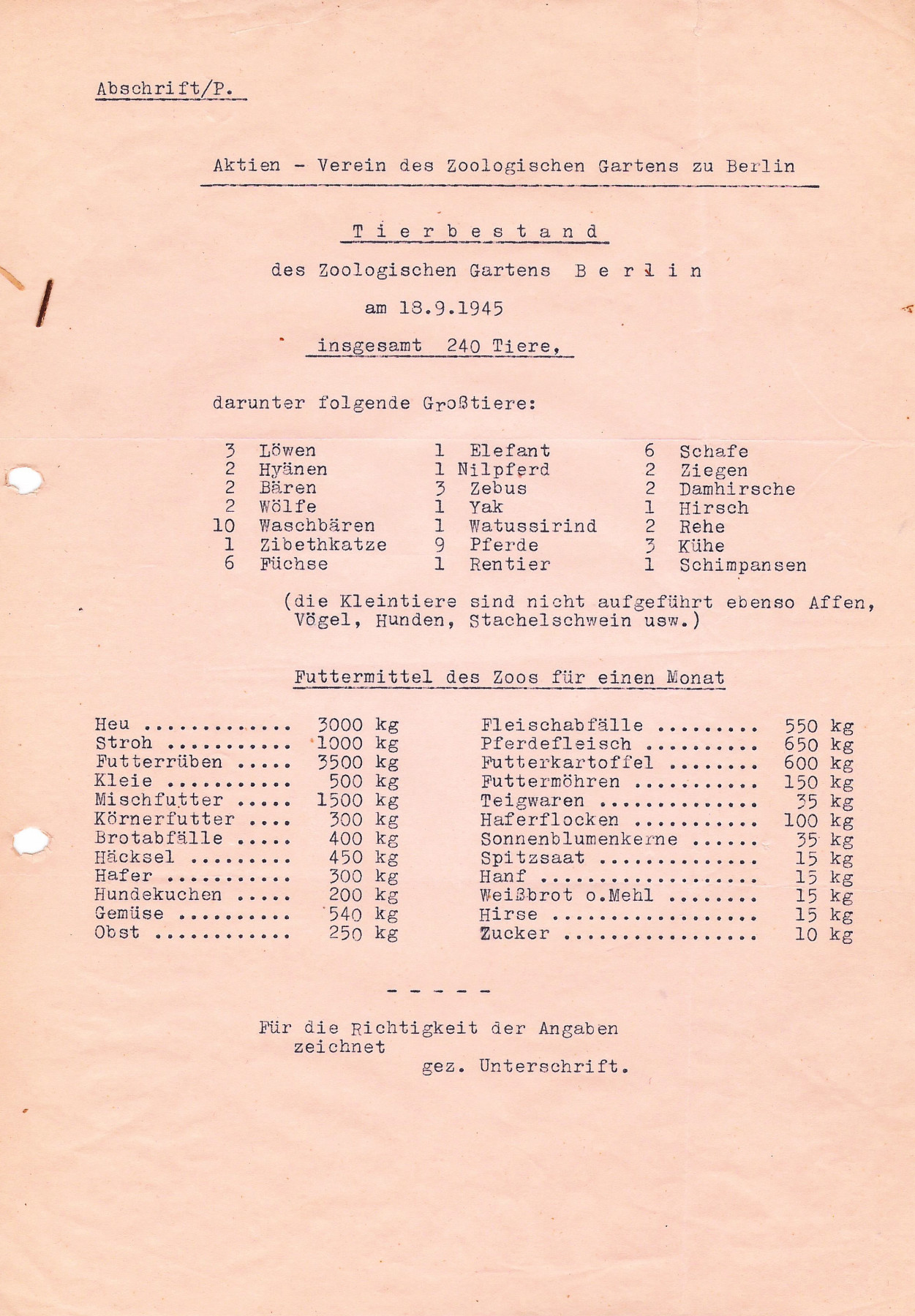

Yet, even the support of the population was not enough. So, who was in fact officially responsible for ensuring that the necessary feed was provided? Feed procurement had to be restructured after the  war. The zoo was in constant need of hay, straw, potatoes, turnips, horse meat, and offal.16 On 6 August 1945, just three days after she had been appointed director of the zoo, Katharina Heinroth turned to the Haupternährungsamt, the main food authority for the city of Berlin, to clarify how feed was to be procured. She sent them a list of the quantities of feed needed. On 10 November 1945, the Allied Control Council decreed that the zoo should be assured of receiving the necessary feed for its 240 animals on a regular basis from the magistrate of the city of Berlin. It was thus the Haupternährungsamt that was responsible for procuring feed.

war. The zoo was in constant need of hay, straw, potatoes, turnips, horse meat, and offal.16 On 6 August 1945, just three days after she had been appointed director of the zoo, Katharina Heinroth turned to the Haupternährungsamt, the main food authority for the city of Berlin, to clarify how feed was to be procured. She sent them a list of the quantities of feed needed. On 10 November 1945, the Allied Control Council decreed that the zoo should be assured of receiving the necessary feed for its 240 animals on a regular basis from the magistrate of the city of Berlin. It was thus the Haupternährungsamt that was responsible for procuring feed.

List of the  feed requirements for the large animals of Berlin Zoo, 18.09.1945. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

feed requirements for the large animals of Berlin Zoo, 18.09.1945. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Once Katharina Heinroth had submitted a  list of the large animals and their feeding requirements, the Haupternährungsamt allocated the necessary rations – here too, the allocated feed was “if at all possible, that which was unsuitable for human consumption”.17

list of the large animals and their feeding requirements, the Haupternährungsamt allocated the necessary rations – here too, the allocated feed was “if at all possible, that which was unsuitable for human consumption”.17  Slaughterhouses were instructed to hand over horse and cattle carcasses to feed the zoo’s carnivores; hospitals supplied from their canteens. The zoo was thus partially integrated into the

Slaughterhouses were instructed to hand over horse and cattle carcasses to feed the zoo’s carnivores; hospitals supplied from their canteens. The zoo was thus partially integrated into the  city’s metabolism as a mechanism for

city’s metabolism as a mechanism for  recycling organic waste.

recycling organic waste.

However, since the animals’ monthly consumption was almost 4,500 kg of feed – including mixed feed, oats and hemp, leftover bread, potatoes and vegetables, meat scraps, and horse meat – in addition to hay and straw, the zoo sometimes still faced shortages.18 At such times, the zoo staff had to improvise. Hemp, millet, and oatmeal were initially nowhere to be found, but barley was available. Katharina Heinroth and her staff replaced missing potatoes with beets or bread scraps; the zookeepers regularly collected potato peelings “from half of Berlin”.19 Daily portions were strictly rationed: “the old elephant ‘Siam’ with his frayed ears, who still has the terror of the bombings in his bones […] is provided 100 pounds of food a day by the Berlin magistrate. The crafty chimpanzee ‘Susi’, on the other hand, has to make do with [food] stamp 5”20 – meaning the lowest category of food stamp, also received by children and pensioners. The Tagesspiegel commented: “The magistrate allocates rations to the animals just as strictly as to humans. Each species has its prescribed quota.”21

Feeding the City

The feed shortage in the zoo reflected the food situation in the city at the time. The city administration also allocated food rations per person per day for the human population. From bread to meat to potatoes and coffee beans – everything was measured out to the gram.22 There were special feed ration cards for certain farm animals, such as horses, cows, and pigs.23 Food scarcity was everywhere, as were shortages in heating fuel. In the long and particularly cold winter of 1946/47, the Tiergarten, a large park bordering the zoo, was almost completely cleared of trees. Hundreds of old trees were turned into firewood and the resulting open spaces were immediately used to grow vegetables. This had been authorised as a temporary measure by the British occupation forces: grain and vegetables grew on about 2,550 plots; horses and oxen pulled ploughs through the former park grounds. The senate arranged for some areas to be planted with green fodder.

Cultivating vegetables in Berlin’s Tiergarten, cleared of its trees, in 1946, with the Reichstag in the background. (Bundesarchiv Image 183-M1015-314. Image: Otto Donath. All rights reserved.)

Vegetable patch in Berlin’s Tiergarten, cleared of its trees, 1945. (Bundesarchiv Image 183-H0813-0600-009. Image: Dreyer. All rights reserved.)

The zoo, in turn, was embedded in the city’s food supply issues in various ways. When it reopened on 1 July 1945, barely a month after the end of the war, it was one of the few places where Berliners could relax and pass the time. But more than this, the zoo was also a hub for the exchange of materials, animals, and information related to supplying the city.

Even before the war, people had turned to the zoo for advice on caring for the animals they kept at home. The focus of such queries now increasingly shifted to questions about  breeding and keeping animals such as chickens, pigeons, furred animals, or goats and rabbits – in other words, working animals or animals that could be kept as livestock; animals that could be used for people’s own consumption, or for breeding.24 A horticultural business wanted a donkey from the zoo to help cultivate vegetables, and in exchange offered young plants in the spring, such as tomatoes, tobacco, and all manner of cabbage plants.25 But the zoo itself did not own a donkey. One couple wanted to buy a dairy sheep “based on a recommendation on the radio […] to improve our meagre diet in these hard times”.26 The zoo was unable to help them either – or the man looking for a breeding hare, “as I would especially like to obtain good fur, in addition to the meat”.27 The list of such examples is long, and in many cases Katharina Heinroth and her staff were unable to fulfil the requests that arrived in large numbers by post, due to their own difficulties with food shortages and feed scarcity. Those who had something to exchange had a better chance of a positive response, as, at the time, the zoo mainly replenished its own animal population through animal exchanges, and animals it agreed to take care of and could simultaneously use for breeding purposes. In December 1945, this almost resulted in an exchange between the zoo and the Daimler-Benz stock association. Due to the acute

breeding and keeping animals such as chickens, pigeons, furred animals, or goats and rabbits – in other words, working animals or animals that could be kept as livestock; animals that could be used for people’s own consumption, or for breeding.24 A horticultural business wanted a donkey from the zoo to help cultivate vegetables, and in exchange offered young plants in the spring, such as tomatoes, tobacco, and all manner of cabbage plants.25 But the zoo itself did not own a donkey. One couple wanted to buy a dairy sheep “based on a recommendation on the radio […] to improve our meagre diet in these hard times”.26 The zoo was unable to help them either – or the man looking for a breeding hare, “as I would especially like to obtain good fur, in addition to the meat”.27 The list of such examples is long, and in many cases Katharina Heinroth and her staff were unable to fulfil the requests that arrived in large numbers by post, due to their own difficulties with food shortages and feed scarcity. Those who had something to exchange had a better chance of a positive response, as, at the time, the zoo mainly replenished its own animal population through animal exchanges, and animals it agreed to take care of and could simultaneously use for breeding purposes. In December 1945, this almost resulted in an exchange between the zoo and the Daimler-Benz stock association. Due to the acute  petrol shortages, the latter was keen to exchange an engine for the zoo’s truck for a horse – in the hope of reverting to literal horsepower to transport food for the company canteen. Katharina Heinroth, however, refused, on the grounds that the zoo’s horses were too valuable.

petrol shortages, the latter was keen to exchange an engine for the zoo’s truck for a horse – in the hope of reverting to literal horsepower to transport food for the company canteen. Katharina Heinroth, however, refused, on the grounds that the zoo’s horses were too valuable.

The Zoo and the City

People not only turned to the Berlin Zoological Garden for its expertise in animal keeping and breeding; the zoo itself was integrated into the city’s supply infrastructure. In 1945, at the request of the district authority for the Tiergarten neighbourhood, it took 250 dairy goats into its care “in order to make a contribution to securing the people’s food supply”.28 We do not know exactly how this collaborative setup worked, or how long it lasted, but such arrangements could and did lead to conflicts over animal feed. When the British military government asked the zoo to take on more domestic animals for the Tiergarten district, Katharina Heinroth replied that the zoo did not have enough feed to do so – to which the British commander responded that the elephant and other animals would then need to be given to other zoos, in order to provide resources for the farm animals.

Animals that were popular among the public, however, made up the zoo’s economic and symbolic capital: “As a zoological garden we would have no interest at all in presenting our visitors with goats or sheep instead of animals from abroad. People don’t come to the zoo to look at chickens or goats, and since we need income to survive, we could soon have to close the zoo.”29 This epitomises the question of what a zoo essentially is and does, and what types of animals it should primarily be concerned with  exhibiting.

exhibiting.

During these years, it was in fact a constant possibility that the zoo might be forced to slaughter some of its animals out of necessity, or give them away due to feed shortages.30 Despite the fact that only 80 animals had survived the war, by September 1945, the zoo had an animal population of 240 – a large part of which it had taken over from a circus. However, on 10 November 1945, the Allied command banned the zoo from acquiring large animals, as no feed could be provided for more animals, especially large ones that required good meat or large quantities of green fodder, and Berlin’s struggling supply infrastructure was not to be further burdened.31 On several occasions, the British commander threatened to close the zoo and evacuate the animals to the West. Katharina Heinroth was always able to ward off this course of action, however.32

What the British commander had in mind was more of an exhibition  showcasing domestic animals. A group of Leghorn chicks, a few lambs and kids, breeding pairs of rabbits and ducklings, which the zoo had reared or bred were to “provide an incentive for the population to engage in simple animal husbandry, and could serve to produce breeding animals to help gradually replenish the livestock in and around Berlin”.33 The purpose of a zoo, and views about what tasks it should fulfill, thus underwent change in times of need. The Allies, the magistrate, and the population all had different expectations of and new jobs for the zoo. Although, in the end, the model exhibition for keeping and breeding

showcasing domestic animals. A group of Leghorn chicks, a few lambs and kids, breeding pairs of rabbits and ducklings, which the zoo had reared or bred were to “provide an incentive for the population to engage in simple animal husbandry, and could serve to produce breeding animals to help gradually replenish the livestock in and around Berlin”.33 The purpose of a zoo, and views about what tasks it should fulfill, thus underwent change in times of need. The Allies, the magistrate, and the population all had different expectations of and new jobs for the zoo. Although, in the end, the model exhibition for keeping and breeding  farm animals did not come to fruition, the zoo did – albeit sometimes against its director’s will – become a place that produced food for animals and humans. It developed into a hub where people exchanged animals and information, and discussed nutritional issues via correspondence. At the same time, the zoo continued with great perseverance to try to adhere to the aspiration – which was both in line with its programme and above all financially motivated – of exhibiting animals with popular appeal from all over the world.

farm animals did not come to fruition, the zoo did – albeit sometimes against its director’s will – become a place that produced food for animals and humans. It developed into a hub where people exchanged animals and information, and discussed nutritional issues via correspondence. At the same time, the zoo continued with great perseverance to try to adhere to the aspiration – which was both in line with its programme and above all financially motivated – of exhibiting animals with popular appeal from all over the world.

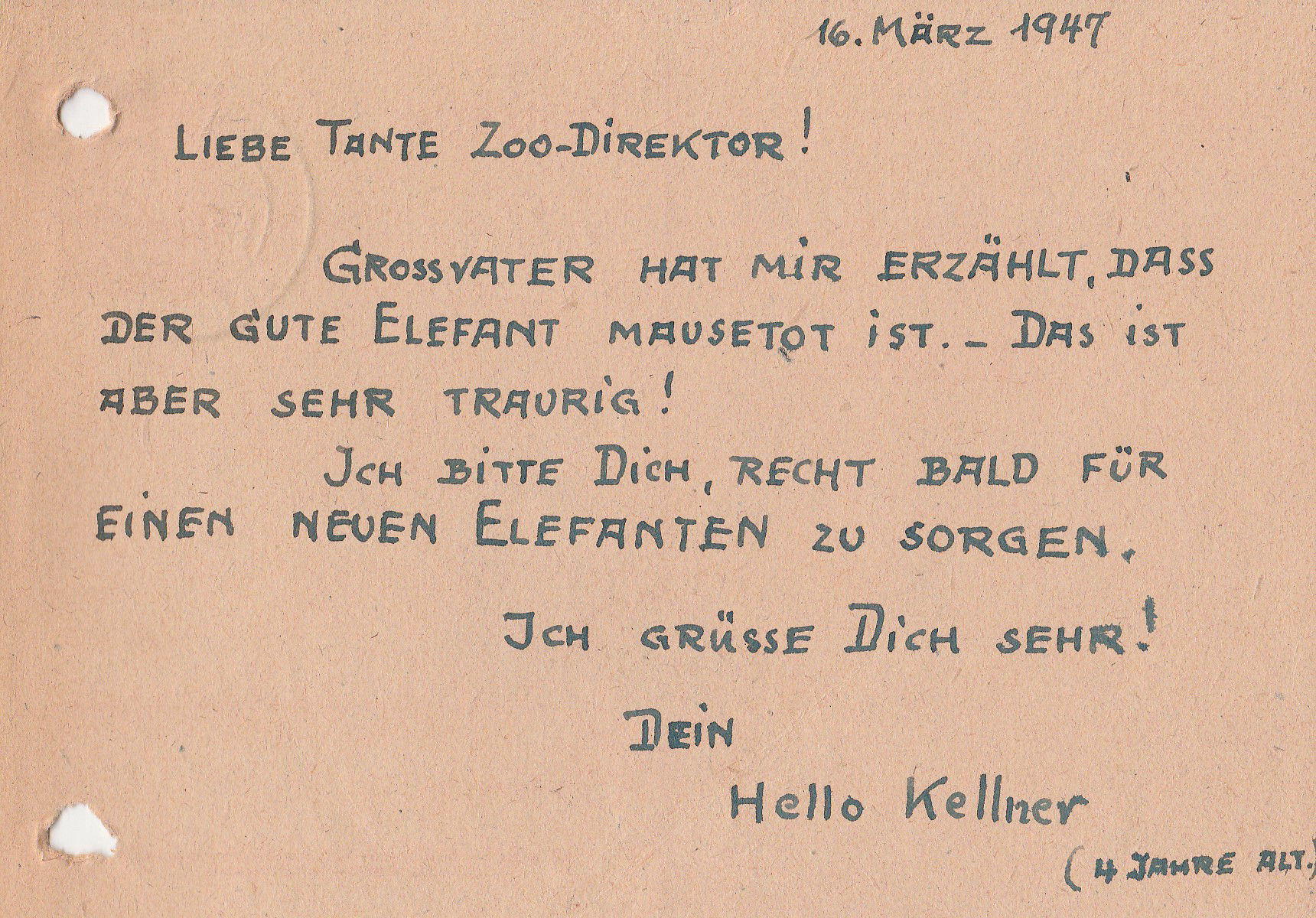

However, the feed situation at the zoo remained challenging, and in March 1947, just two years after the end of the war,  “Siam” the elephant died. The articles in the daily newspapers read: “half frozen to death […] our zoo pachyderm has now died of starvation”.34 The (highest possible) body weight of zoo animals was indeed long considered an indicator of good animal husbandry, as the example of the famous zoo gorilla

“Siam” the elephant died. The articles in the daily newspapers read: “half frozen to death […] our zoo pachyderm has now died of starvation”.34 The (highest possible) body weight of zoo animals was indeed long considered an indicator of good animal husbandry, as the example of the famous zoo gorilla  “Bobby” shows. Yet, “Siam” had not in fact starved to death, but had died of a chronic intestinal inflammation and severe changes to his heart muscle. This was the finding of the autopsy carried out jointly by the Veterinary School and the Zoological Museum (part of the Natural History Museum). Was this misinformation or deliberate feint? We can only speculate. Difficulties with shortages in Berlin were certainly a recurring theme in the Telegraf. And perhaps it was a comforting idea to think that ‘our zoo elephant’ was struggling with hunger just like the people of Berlin?

“Bobby” shows. Yet, “Siam” had not in fact starved to death, but had died of a chronic intestinal inflammation and severe changes to his heart muscle. This was the finding of the autopsy carried out jointly by the Veterinary School and the Zoological Museum (part of the Natural History Museum). Was this misinformation or deliberate feint? We can only speculate. Difficulties with shortages in Berlin were certainly a recurring theme in the Telegraf. And perhaps it was a comforting idea to think that ‘our zoo elephant’ was struggling with hunger just like the people of Berlin?

There are many instances of (zoo) animals serving as figures for people to identify with or project their feelings onto during hard times. Mieke Roscher and Anna-Katharina Wöbse have examined the role of zoo animals in providing support, and the zoo as a place of social rapprochement between humans and animals in times of crisis. Their work focuses specifically on Berlin and London during the Second World War.35 Their findings could also be applied to the postwar period, however. The sense that animals and humans shared the same fate, a feeling of solidarity and belonging to a community of suffering was something that was especially important. Evidence of animals having been commemorated as war victims can be found as early as the 19th century: At the entrance to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, for example, there is a plaque commemorating the elephants and kangaroos of the menagerie there that were among the victims of war after the Siege of Paris in 1870. It may therefore come as no surprise that the zoo received many letters expressing sympathy and regret over the death of the Berlin Zoo’s last elephant. At the same time, many wanted to know when there would be a new elephant to come and visit.

Condolence postcard from four-year-old Hello Kellner to Berlin Zoo on the death of “Siam”. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Here, too, Katharina Heinroth could only reply: “For the time being, we will not acquire a new elephant because of the feed shortages.”36 But there were also outraged voices who – assuming that the elephant had starved to death – wanted to know why the zoo did not give away its animals if it could no longer feed them:

“But now we have read [in the newspaper] that you are already trying to get a new elephant. Dear madam director, hand on heart, how can you justify this! In a matter of weeks, maybe months, it will merely suffer the same fate as Siam. Just for the publicity of having an elephant again – I wouldn’t do it. We know why we have to starve, but an animal does not understand. We have to do without so much that is precious and beautiful, we would rather not have an elephant at the moment. Because when we come and visit it, I am sure we won’t be able to stop ourselves from thinking ‘It’s hungry just like the rest of us.’”37

In the early postwar years, the relationship between the zoo and the people of Berlin oscillated between care and competition. The city – the population as well as the authorities – supported the zoo in matters of feed. For example, “a tribe of about 20 children” was always on hand to collect chestnuts and acorns for the zoo animals, which quickly amounted to many hundredweight.38 In 1948 however, the central authority for drugs and wild fruits (Zentrale für Drogen und Wildfrüchte) asked the zoo to stop allowing chestnuts to be collected for feeding purposes, because they were needed to feed the population, and because human labor was an important resource. The visitors who brought bread or potato peelings for the animals were, in turn, forbidden from collecting acorns for their own use on the zoo grounds. Inspectors searched bags and backpacks at the exits: “At present we are salvaging several hundredweight of acorns from the visitors at the ticket offices every day”, the zoo director noted in 1948.39 Particularly in times of need, humans and animals were competing for the same resources. Katharina Heinroth was aware of this dilemma: “Our keepers gather potato peelings from half of Berlin with touching diligence. But these are also becoming rarer, as, in these times of great need, many people are collecting the potato peelings for their own use. I know some people who live on potato peelings.”40

Depending on your perspective, the zoo was a hub for the exchange of animals and information; a place for the illegal procurement of food, where acorns and animals were stolen; a part of the city’s supply infrastructure; or a burden on its food supply – a situation that only gradually began to normalise in the early 1950s. “We have all kinds of plans for the spring”, wrote Katharina Heinroth in a letter in the spring of 1950, “the gardening should stop now, because the food situation has improved substantially for the people of Berlin and vegetables can be bought at the markets again. We can now beautify our grounds again”.41 One thing becomes clear in view of these postwar years: while zoos understand their primary purpose as being  to exhibit wild animals in an urban environment, they are not divorced from the city that surrounds them and its political, social, and economic situation. Crises such as the postwar period present the zoo with new challenges to which it must respond, and in the course of which the role of the institution, as well as the status and value attributed to its animals, are subject to changes. In light of the challenges posed by climate justice and social justice today, we are faced with the important question as to what we want the zoo of the future to look like.

to exhibit wild animals in an urban environment, they are not divorced from the city that surrounds them and its political, social, and economic situation. Crises such as the postwar period present the zoo with new challenges to which it must respond, and in the course of which the role of the institution, as well as the status and value attributed to its animals, are subject to changes. In light of the challenges posed by climate justice and social justice today, we are faced with the important question as to what we want the zoo of the future to look like.

- In 1938, there were 3,715 animals; in 1944 there were still 1,700 animals. Cf. half-yearly report for the supervisory board meeting of 10.08.1955, AZGB N 4/2.↩

- Progress report of the Zoological Garden from 03.05. to 23.05.1945, AZGB O 0/1/75.↩

- K. Heinroth to Paula, 01.03.1946, AZGB N 4/12.↩

- “Siam erhält Stubenarrest: Wintervorbereitungen im Zoo”. Das Volk, 04.11.1945. As one might imagine, the practice of converting open spaces for the cultivation of vegetables and potatoes was widespread. The garden of the Natural History Museum, for instance, was also reserved for growing vegetables for staff until 1949.↩

- Cf. progress report of the Zoological Garden from 03.05. to 23.05.1945, AZGB O 0/1/75. As a result of the war, many of the animals had been killed, and large parts of the zoo buildings destroyed, which is why there were a lot of open spaces once the debris had been removed.↩

- K. Heinroth to L. Rüppell, n.d. [likely April/May 1946], AZGB N 4/12. Cf. also the annual report of the park department of the Berlin Zoological Garden 1945: “The large elephant enclosure and the unoccupied areas in the ostrich pen and in front of the pheasant house were used to grow Jerusalem artichokes and beets. The two main promenades were sowed with potatoes.”↩

- “Most of the lawns will be sowed with turnips and fodder, the feed shortage is terrible.” K. Heinroth to Paula, 1.3.1946, AZGB N 4/12 I. Cf. also K. Heinroth to L. Rüppell, n.d. [likely April/May 1946], AZGB N 4/12. Heinroth wrote in a letter: “Some of the retinue use the free enclosures as allotments.” Progress report by Katharina Heinroth, 18.09.1945, AZGB N 4/2.↩

- Annual report from 01.04.1949 to 31.12.1949, AZGB N/4/2.↩

- K. Heinroth to P. Chudy, 17.07.1948, AZGB O 0/1/60.↩

- K. Heinroth to W. Börner, 19.07.1947, AZGB O 1/2/37. The feed shortage and the fact that no new animals could be acquired was to a large extent due to the zoo’s financial problems. After the division of the city by the Potsdam Agreement, its accounts were located in banks in the eastern part of the city. Moreover, the zoo initially had little income.↩

- “Sorgen im Berliner Zoo”. Neue Zeit, 18.09.1948.↩

- “Der Zoo braucht dringend Hilfe”. Die Neue Zeitung [München], 07.04.1949.↩

- The magazine was initially published by the Allgemeiner Deutscher Verlag in East Berlin, until 1948, when the democratic women’s association of Germany (Demokratischer Frauenbund Deutschlands, DFD) took over the editorship until the journal was discontinued at the end of 1962. After that, by decision of the SED secretariat, the magazine was published by Deutscher Frauenverlag GmbH Berlin, and from 1953 by the Verlag für die Frau, Leipzig. In 1963, the magazine Für Dich became the successor to Frau von heute.↩

- “Zoo: Junge Tiere, junge Pflanzen, junge Menschen”. Die Frau von heute, 07.05.1946.↩

- This attitude changed in the 1950s, at the time of the economic boom, when it was announced that: “Whoever wants to prove their love for animals by satisfying their hunger should remember that animals are not a recycling facility for those foods that have become inedible for human beings.” “Falsche Tierliebe”. Gießener Anzeiger, 16.04.1960. See also

Feeding Prohibited.↩

Feeding Prohibited.↩ - K. Heinroth to the Haupternährungsamt of the city of Berlin, 06.08.1945, AZGB N 4/2.↩

- Cf. AZGB O 1/1/2.↩

- Cf. magistrate of the city of Berlin, department for food and nutrition to the Zoological Garden Berlin, 17.11.1945, AZGB O 1/1/2.↩

- K. Heinroth to E. Mohr, 22.01.1946, AZGB N 4/12.↩

- Daniel de Luce. “Lebensmittelkarte 5 im Berliner Zoo”. Tägliche Rundschau, 17.12.1946.↩

- “Spinat oder Hirsche: Ein Frühlingsspaziergang durch den Berliner Zoo”. Der Tagesspiegel, 03.04.1947.↩

- Cf. Verordnungsblatt (VOBl.) der Stadt Berlin 1945, no. 1, July 1945: 5.↩

- “Einführung von Futtermittelkarten”. Verordnungsblatt (VOBl.) der Stadt Berlin 1945, No. 7, 20.09.1945: 81.↩

- Cf. AZGB O 1/2/42.↩

- Horticultural business F. Rauhut to K. Heinroth, 14.01.1947, AZGB O 1/2/42.↩

- M. Metzner to K. Heinroth, 09.04.1947, AZGB O 1/2/42.↩

- H. Binck to the Zoological Garden Berlin, 16.11.1947, AZGB O 1/2/42.↩

- Progress report by Katharina Heinroth, 18.09.1945, AZGB N 4/2.↩

- File memo Katharina Heinroth, 19.03.1946, AZGB O 0/1/75.↩

- When guinea pig breeding was being reestablished, the zoo was “often forced to use guinea pigs as feed due to food scarcity”. K. Heinroth to J. Roscher, 23.02.1947, AZGB O 1/2/42. On the threat of evacuation, cf. also K. Heinroth to K. Lorenz, 12.10.1948, AZGB N/4/12; K. Heinroth to E. Mohr, 28.02.1946, in: AZGB N 4/12.↩

- Between May and August 1945, the number of animals increased from 194 to 240, mainly due to the intake of animals from the Brumbach Circus.↩

- Cf. Katharina Heinroth. Mit Faltern begann’s: Mein Leben mit Tieren in Breslau, München und Berlin. München: Kindler, 1979: 154-157. The Second World War had, to a greater or lesser extent, destroyed many zoos throughout Europe. Moreover, during the First and Second World Wars, military units of the Reichswehr and the Wehrmacht captured animals in the conquered territories of Europe and handed them over to the zoological gardens of the Reich capital. In 1939, Lutz Heck also brought valuable show animals, including an elephant, from Warsaw Zoo to German zoos. Cf. Marianna Szczygielska. “Elephant Empire: Zoos and Colonial Encounters in Eastern Europe”. Cultural Studies(2020): 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1780280; see also

Catching Animals.↩

Catching Animals.↩ - K. Heinroth to the magistrate of the city of Berlin, department for food and nutrition, 20.03.1946, AZGB O 1/1/2. Cf. also K. Heinroth to the Allied commander of the city of Berlin, 15.05.1946, AZGB O 1/1/2.↩

- “The last of Berlin’s pachyderms ‘Siam’ starved and froze half to death in March last year.” Cf. “Auf den Spuren des Elefanten”. Der Kurier, 07.02.1948; and “‘Siam’ unter der Bandsäge”. Telegraf, 21.03.1947.↩

- Anna-Katharina Wöbse and Mieke Roscher. “Zootiere während des Zweiten Weltkrieges: London und Berlin 1939-1945”. WerkstattGeschichte 56 (2010): 44-62.↩

- K. Heinroth to W. Börner, 14.10.1947, AZGB O 1/2/42.↩

- C. Gutschmidt to K. Heinroth, 26.03.1947, AZGB O 1/2/37.↩

- Cf. K. Heinroth to E. Schmidt, 13.10.1948, AZGB O 0/1/274. Food shortages were already a major issue for both people and zoo animals during the First World War. Especially in the so-called “Steckrübenwinter” (“turnip winter”) of 1916/17, it proved difficult to obtain grain and potato products, which resulted in riots and looting in many German cities. The notion that animals were competing with humans for food prompted mass slaughtering, which ultimately exacerbated the situation more than anything else. Cf. Nastasja Klothmann. Gefühlswelten im Zoo: Eine Emotionsgeschichte 1900-1945. Bielefeld: transcript, 2015.↩

- K. Heinroth to E. Schmidt, 13.10.1948, AZGB O 0/1/274.↩

- K. Heinroth to E. Mohr, 22.01.1946, AZGB N/4/12.↩

- K. Heinroth to U. Bergman, 07.03.1950, AZGB N 4/12. Cf. also AZGB O 1/1/1.↩