Photograph from the 1903 Offizieller Katalog der Deutsch-Kolonialen Jagdausstellung (Karlsruhe: G. Braunschen Hofbuchdruckerei, 1903: 62-63) showing ethnographic objects and animal trophies side by side.

This photograph shows the room of the trading house Karl Eisengräber in the 1903 German-Colonial Hunting Exhibition. It is evidence not only of the complex visual rhetoric of 19th-century European imperial pursuits, but also tells us something about the role attributed to animals in this context, showing how  animals were caught and

animals were caught and  displayed

displayed

The event was organised by the Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft (the German Colonial Society) that was created in 1887 in order to promote the exploration of East Africa and expand the German colonial agenda.1 In 1902, the society organised its first colonial congress in Berlin; followed by the hunting exhibition in Karlsruhe in 1903. As with the rest of the exhibition, the walls in the room on the photograph displayed animals as  hunting trophies. But what is special here is that the skulls of buffaloes, rhinoceros, elephants, and antelopes were exhibited side by side with colonial goods: the result of extractive colonial agriculture such as coffee, cacao, vanilla, and peanut oil. These ‘raw products’ were shown alongside artefacts, and both could be purchased from ‘German Swahilis’, so as to convince the audiences of the quality of the products and the craft.2 According to the catalogue, ethnographic collections were added to the hunting exhibition in order to convey to the visitors the most “atmospheric image possible”3 of the whole of the German colonial territories. In this way,

hunting trophies. But what is special here is that the skulls of buffaloes, rhinoceros, elephants, and antelopes were exhibited side by side with colonial goods: the result of extractive colonial agriculture such as coffee, cacao, vanilla, and peanut oil. These ‘raw products’ were shown alongside artefacts, and both could be purchased from ‘German Swahilis’, so as to convince the audiences of the quality of the products and the craft.2 According to the catalogue, ethnographic collections were added to the hunting exhibition in order to convey to the visitors the most “atmospheric image possible”3 of the whole of the German colonial territories. In this way,  big game hunting was visually associated with natural resources and the expanding colonial market, and this exhibition suggested a connection between hunting campaigns, colonial crafts, and economical gain.

big game hunting was visually associated with natural resources and the expanding colonial market, and this exhibition suggested a connection between hunting campaigns, colonial crafts, and economical gain.

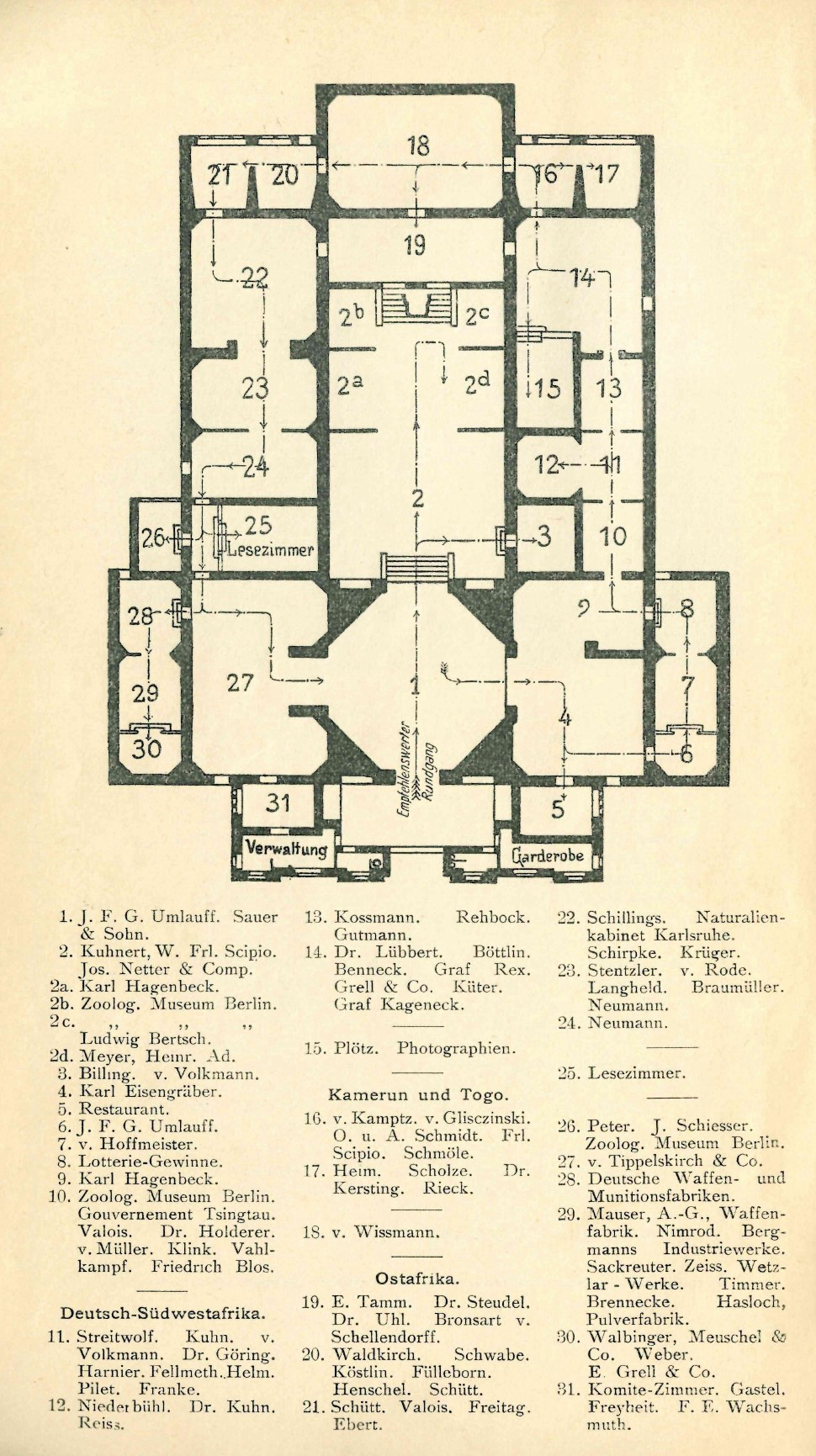

Page 2 of the Offizieller Katalog der Deutsch-Kolonialen Jagdausstellung from 1903 contained a floor plan of the exhibition with a legend listing all 31 rooms and exhibitors.

This strategy to combine a hunting exhibition with a colonial exhibition continued throughout the whole Karlsruhe presentation, as can be seen from this plan. The rooms displayed animal skulls, horns, and skins, alongside hunting equipment, charts of the territories under German colonial rule, oil paintings, and crafted colonial products. This display scheme echoed, on the one hand, the colonial practices of simultaneously collecting cultural and natural objects. On the other hand, the exhibitionary strategy of reconfiguring different types of  colonial objects was a means to convey an image of imperial pursuit that simultaneously included economic, scientific, and cultural objects to display the potential for colonial appropriation. Two rooms were indeed explicitly dedicated to science. The ‘scientific section’, organised by the Zoological Museum in Berlin, showed objects from German colonies, among them zebra skins and antelope horns.4 The aim of this section was “deepening the knowledge about animals in the colonies” by displaying the “typical forms” of the different territories.5 Correlating different types of objects and collections was a way to bridge disciplinary borders and a visual strategy to present an image of the colonies “as multifaceted as possible”, as the catalogue explained.6 What the Karlsruhe Exhibition can thus show us today is how hunting, selling, collecting, displaying,

colonial objects was a means to convey an image of imperial pursuit that simultaneously included economic, scientific, and cultural objects to display the potential for colonial appropriation. Two rooms were indeed explicitly dedicated to science. The ‘scientific section’, organised by the Zoological Museum in Berlin, showed objects from German colonies, among them zebra skins and antelope horns.4 The aim of this section was “deepening the knowledge about animals in the colonies” by displaying the “typical forms” of the different territories.5 Correlating different types of objects and collections was a way to bridge disciplinary borders and a visual strategy to present an image of the colonies “as multifaceted as possible”, as the catalogue explained.6 What the Karlsruhe Exhibition can thus show us today is how hunting, selling, collecting, displaying,  classifying, and researching big game animals were all part of the colonial appropriation of the territory.

classifying, and researching big game animals were all part of the colonial appropriation of the territory.

- The Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft aggregated the former initiatives of the Deutscher Kolonialverein, founded in 1882 in Frankfurt, and the Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, founded in 1884 by colonial criminal and ideologist Carl Peters (1856-1918) to secure the colonial rule of what was German East Africa. (The colonised territory of ‘German East Africa’ comprised today’s Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda as well as some parts of Mozambique.)↩

- “Raum 4: Eisengräber”. In Offizieller Katalog der Deutsch-Kolonialen Jagdausstellung. 2nd ed., Karlsruhe: G. Braunschen Hofbuchdruckerei, 1903: 61.↩

- German original: “ein möglichst stimmungsvolles Bild”. T. Rehbock. “Vorwort”. In Offizieller Katalog der Deutsch-Kolonialen Jagdausstellung, 1903: 11.↩

- “Raum 2 b und c: Zoologisches Museum, Berlin”. In Offizieller Katalog der Deutsch-Kolonialen Jagdausstellung, 1903: 55.↩

- German original: “die Kenntnis der Tierwelt unserer Kolonien zu vertiefen” Rehbock, 1903: 11.↩

- German original: “um das Gesamtbild der Ausstellung möglichst vielseitig zu gestalten”. Ibid.: 11.↩