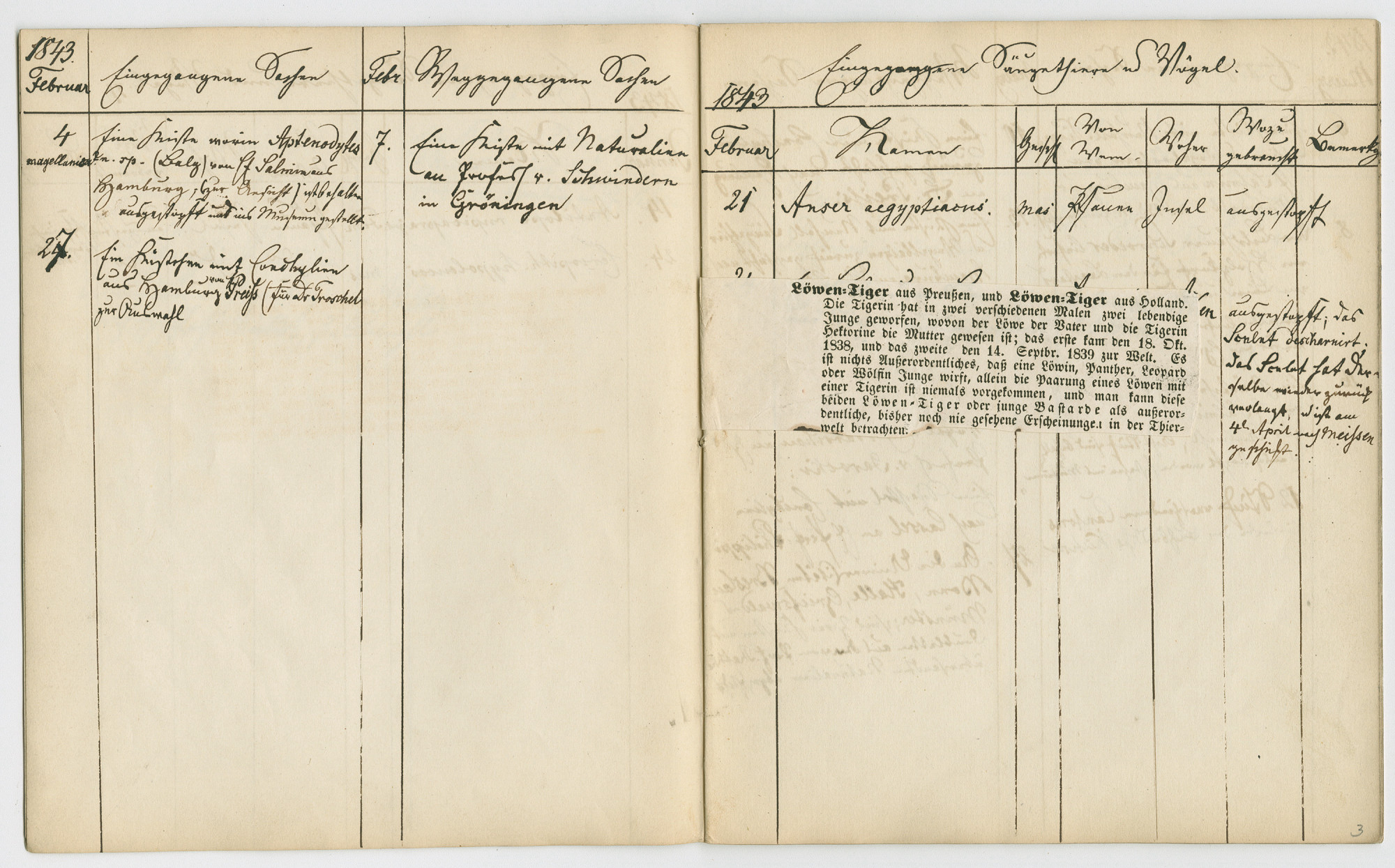

Logbook for 1843 from the Zoological Collection displaying the month of February. (MfN, HBSB, ZM SI Verwaltungsakten, Tagebuch Beyer, 1843. All rights reserved.)

What kinds of stories can records like this  logbook tell us? Preparator Friedrich Beyer, who worked at the Zoological Museum in Berlin from 1817 to 1851, used logbooks to document not just the types of consignments that went in and out of the museum but also who needed them where and why. His notes belong to the collection’s media of record-keeping, together with

logbook tell us? Preparator Friedrich Beyer, who worked at the Zoological Museum in Berlin from 1817 to 1851, used logbooks to document not just the types of consignments that went in and out of the museum but also who needed them where and why. His notes belong to the collection’s media of record-keeping, together with  labels,

labels,  specimen lists and

specimen lists and  inventory books.

inventory books.

Alongside frequent mentions of boxes filled with bird skins, fish, and amphibians, there are also entries about extraordinary arrivals such as a ‘monstrous chicken’s egg’ and a ‘lion-tiger’. They provide us with detailed information about the context and afterlife of these animal objects. The handwritten note that records the arrival of the ‘lion-tiger’ at the Zoological Museum in February 1843, for example, is supplemented with a printed excerpt from part of a leaflet that the animal tamer Anton van Aken used to advertise his “Great Menagerie of Rare and Strange Animals”. It lets us know not just the ‘lion-tiger’s’ birth date, 18 October 1838, but also what kind of “extraordinary, never-before-seen phenomenon” it was. The logbook is thus a collection of notes whose various sources, firstly, inform us about the life of the ‘lion-tiger’ in the circus but, secondly, also tell us that, although the animal was mounted as a taxidermy in the museum after its death, its skeleton was sent back to van Aken at his express wish.

Work materials, which appear in the form of deliveries of spirits, glass eyes, and wooden heads, also point to a history dwelling within the logbooks. Just like the comments on preparation, they provide us with insights into the everyday work of an  animal preparator. Aside from skeletonizing, preparing, and preserving specimens in spirits, it notes in various passages: “unsuitable for stuffing due to very inadequate coat, so only keep the heads”, or “had died more than 3 days before and was therefore entirely useless”. So, not every animal reached the museum in a state that was deemed acceptable. Much was already

animal preparator. Aside from skeletonizing, preparing, and preserving specimens in spirits, it notes in various passages: “unsuitable for stuffing due to very inadequate coat, so only keep the heads”, or “had died more than 3 days before and was therefore entirely useless”. So, not every animal reached the museum in a state that was deemed acceptable. Much was already  rotting, had been

rotting, had been  “eaten by rats”, or did not meet aesthetic standards.

“eaten by rats”, or did not meet aesthetic standards.

What these logbooks also illustrate are the  connections between the Zoological Museum and other institutions and their history. Berlin’s Zoological Garden first appears in the logbooks as a source of animals in 1844, the year of its founding, while the now disbanded royal menagerie on Pfaueninsel (Peacock Island), in the south of Berlin, disappears from the lists. This change is not the only thing that reflects the historical transition from royal menageries to public zoos. The increasingly close connections between the

connections between the Zoological Museum and other institutions and their history. Berlin’s Zoological Garden first appears in the logbooks as a source of animals in 1844, the year of its founding, while the now disbanded royal menagerie on Pfaueninsel (Peacock Island), in the south of Berlin, disappears from the lists. This change is not the only thing that reflects the historical transition from royal menageries to public zoos. The increasingly close connections between the  zoo and the museum also become visible due to the continuous growth in the number of animals being supplied by the Zoological Garden as the number of private deliveries waned in subsequent years.

zoo and the museum also become visible due to the continuous growth in the number of animals being supplied by the Zoological Garden as the number of private deliveries waned in subsequent years.

Friedrich Beyer’s logbooks do not just provide us with a treasure trove of object histories like that of the ‘lion-tiger’, but also give us insights into the methods of animal preparation, taxidermy, and  displays, as well as into institutional entanglements and networks of object transfer.

displays, as well as into institutional entanglements and networks of object transfer.