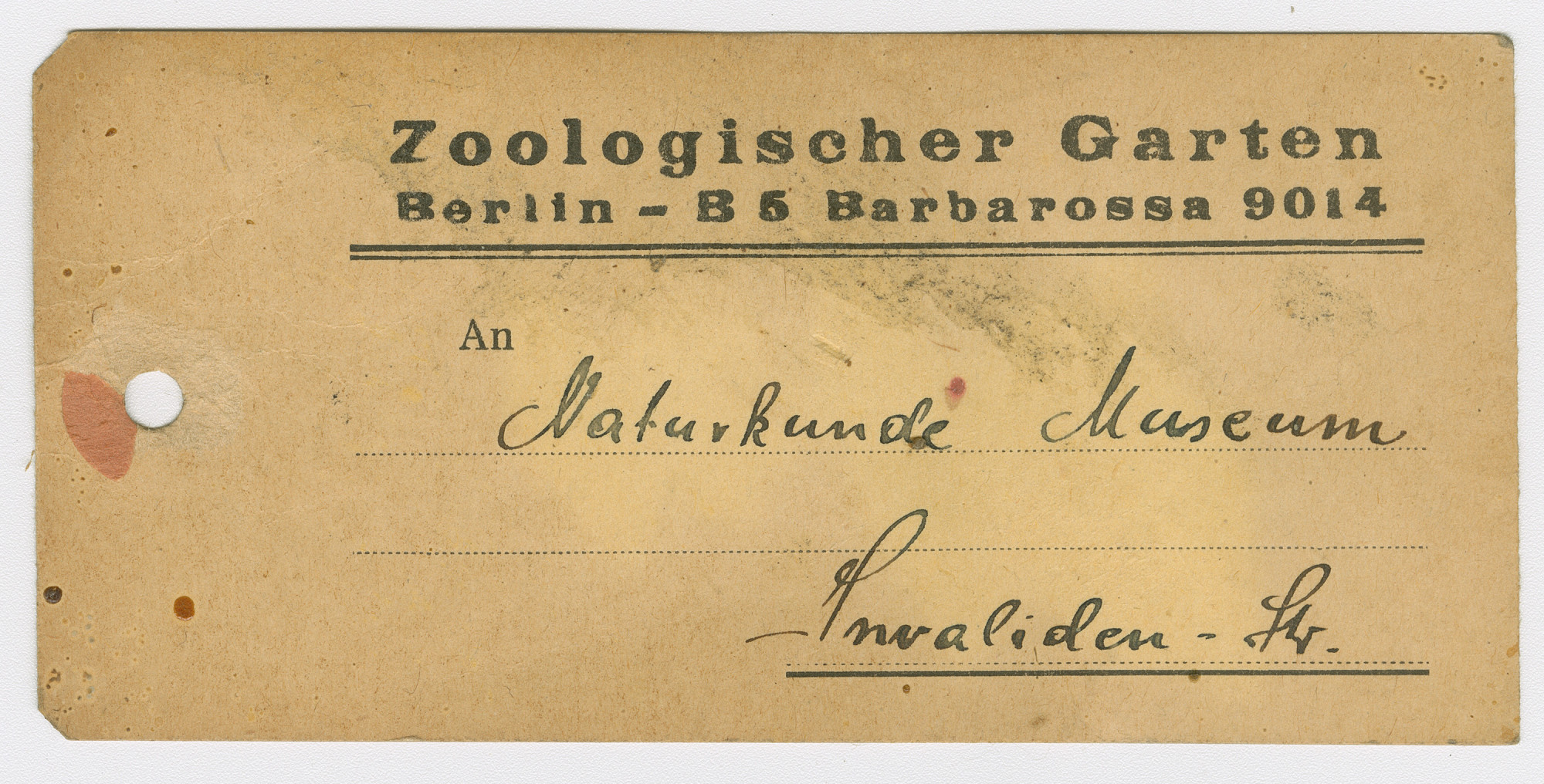

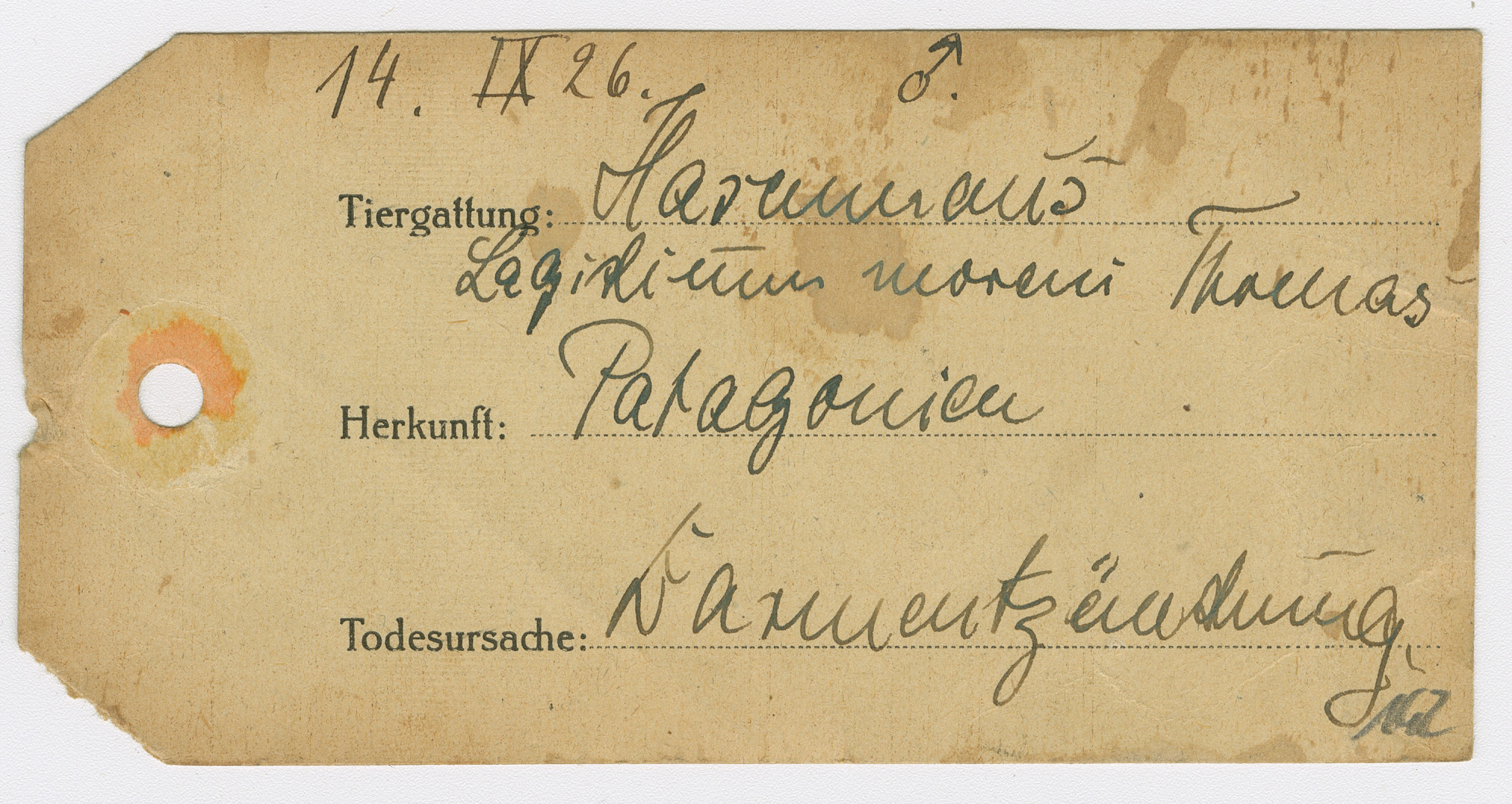

A mobile thing of knowledge: In the 1920s and 1930s, labels like this were attached to the bodies of animals that were sent on by the zoo after their deaths. They note where the animal carcass was to be sent. (MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, Bl. 020 recto. All rights reserved.)

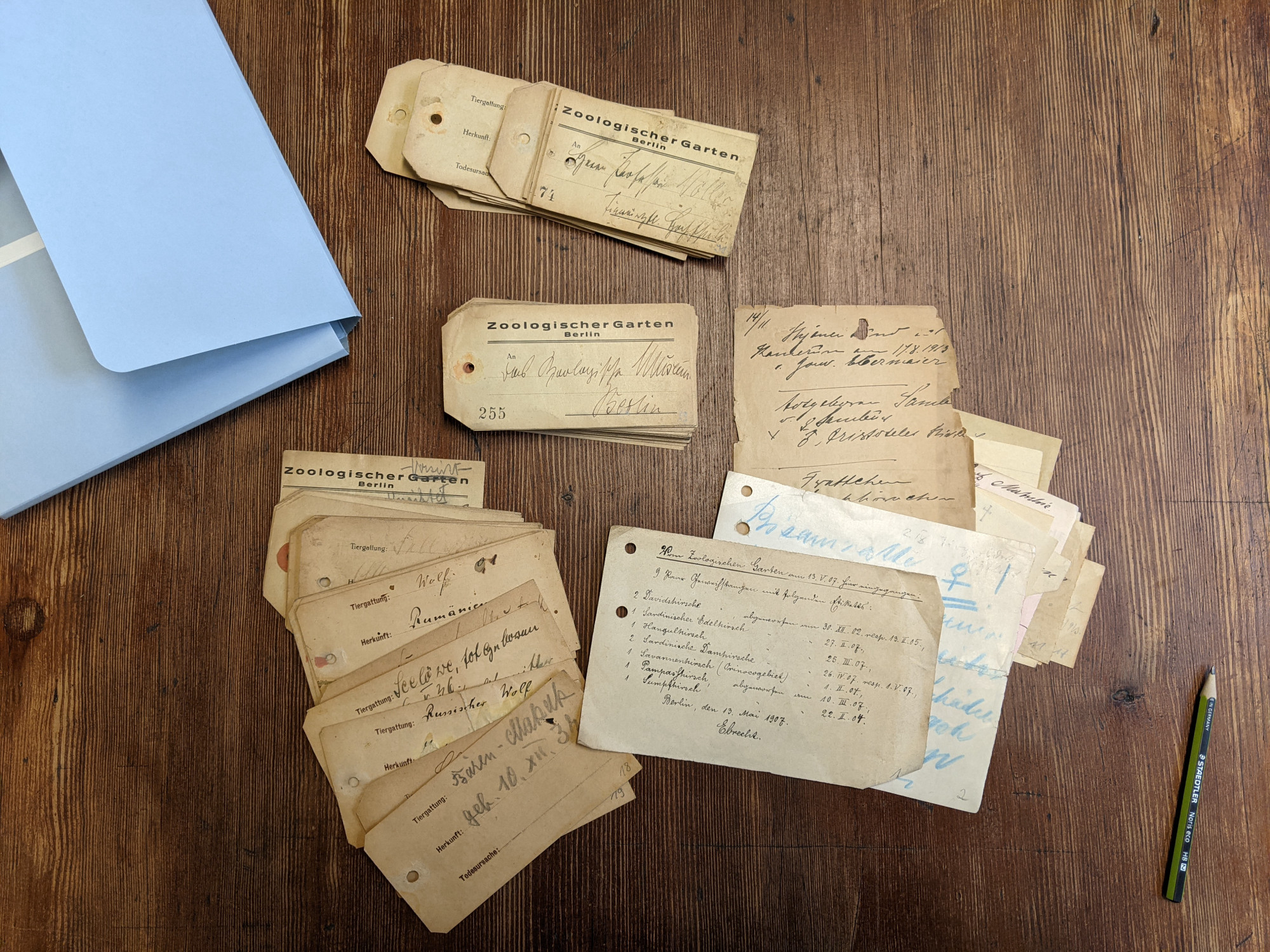

A discovery: a pile of old tags from Berlin Zoological Garden, most of them from the 1920s and 1930s, that had been filed in a folder in the archive of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin containing letters that had been sent between the Zoological Museum and the Zoological Garden back then. These labels, which were attached to the animals as ‘accompanying documents’ when they left the zoo  after their deaths, are material traces of the relationship between the zoo and the museum at the time. What can they tell us?

after their deaths, are material traces of the relationship between the zoo and the museum at the time. What can they tell us?

Historical labels from the Zoological Garden in an archive folder in the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin: material traces of the history of the relationship between the zoo and the museum in Berlin. (MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, image: Sarina Schirmer/MfN. All rights reserved.)

They indicate that it was not just the odd animal being sent from the museum to the zoo every now and then. However, if we take a closer look, we see more addressees noted on the documents, to be precise, the institutions that formed the stations on the animal’s journey to the museum. Together with the destination, the labels thus also mark the paths the animal bodies took through Berlin.

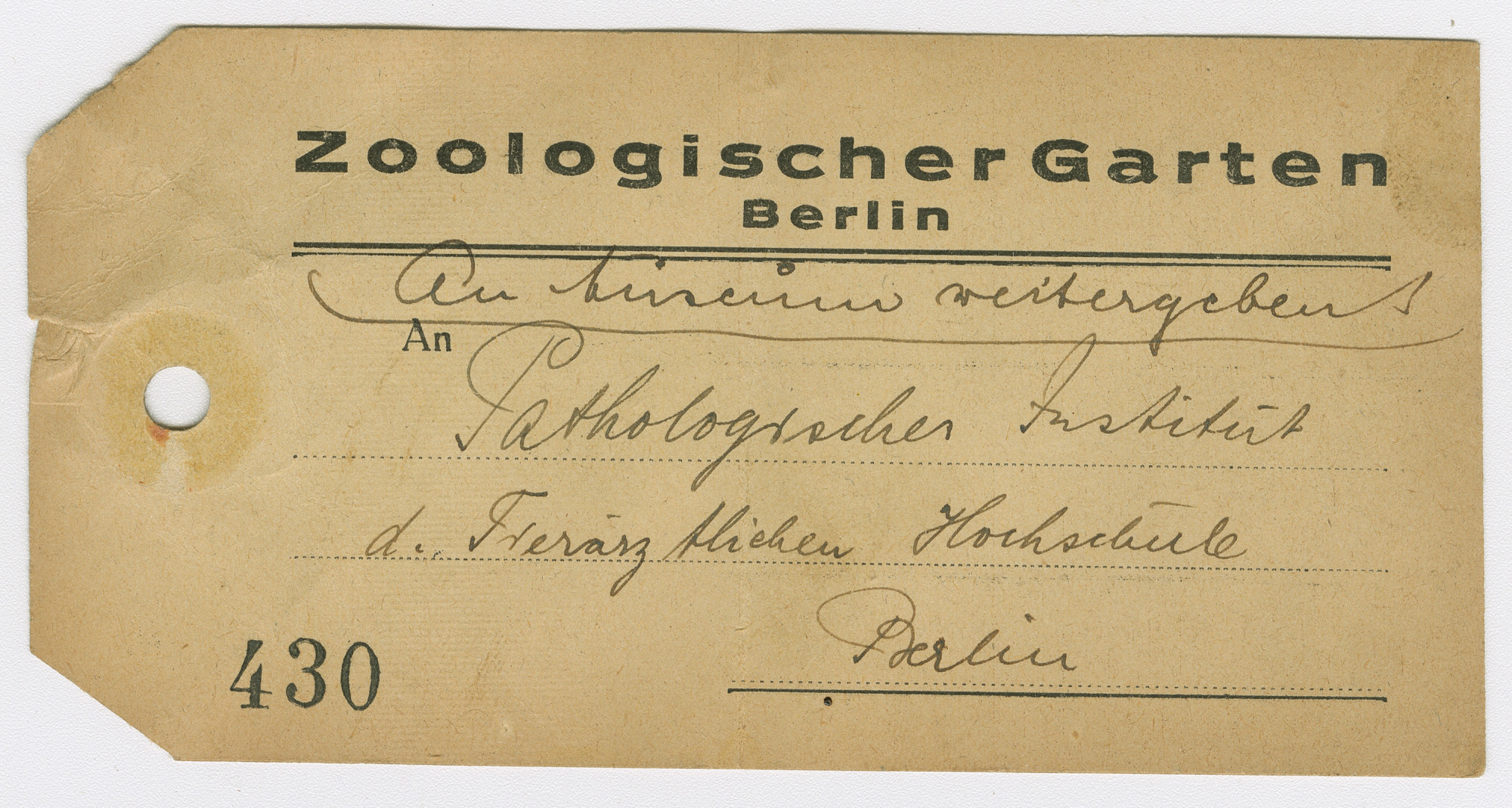

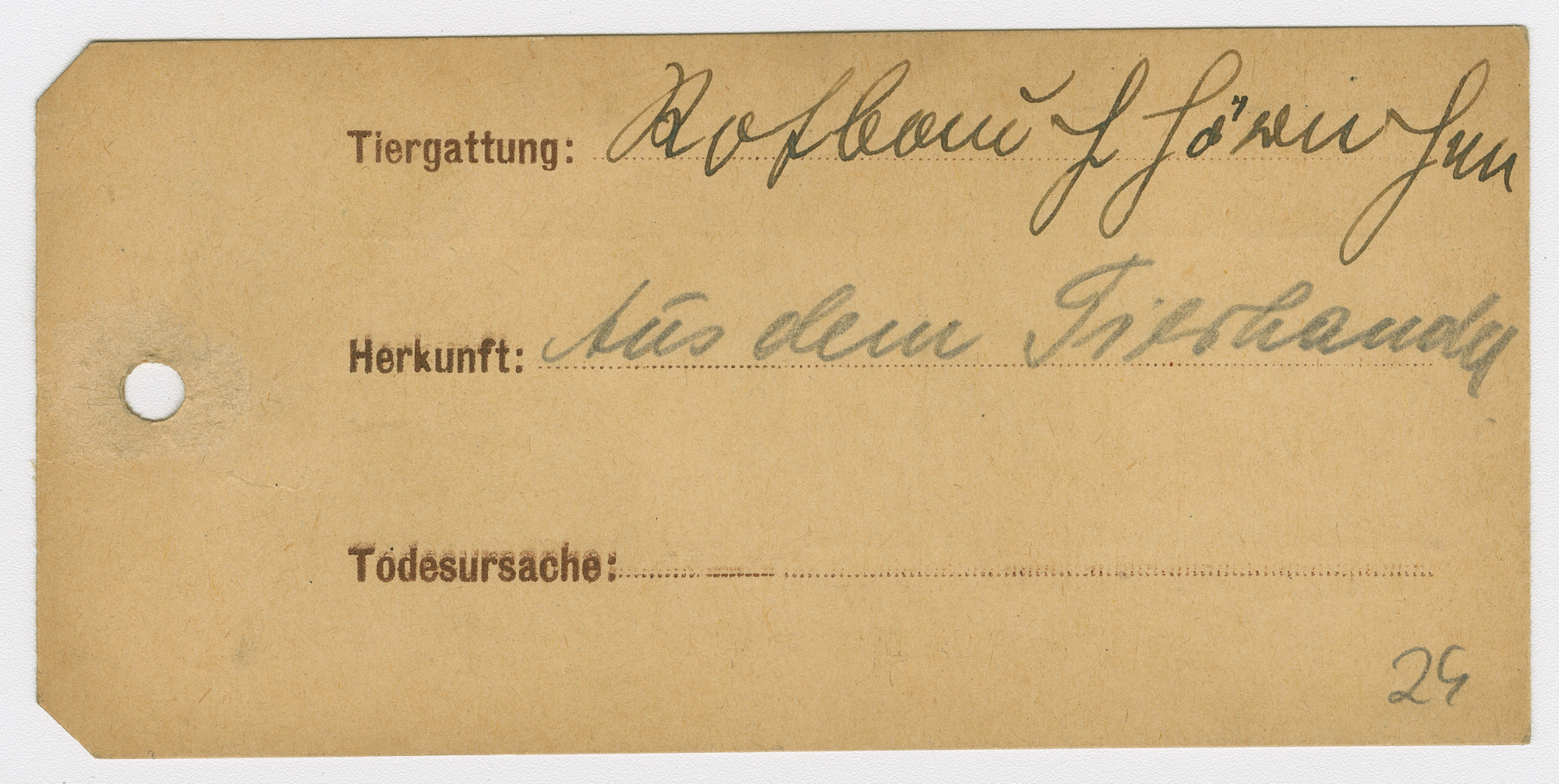

Animal logistics on paper. The instructions on the labels reveal the paths that zoo animals took through a network of local institutions. (MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, Bl. 057 verso; MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, Bl. 140 recto. All rights reserved.) For translation, see footnote.1

These notes, which were once mobile, also helped these different actors to make internal  logistical arrangements. They often provide instructions for further use – ‘With a request for examination and transfer to the Zoolog. Museum on Invalidenstraße’, says one, for example. The first journey that an animal took after its death usually led from the zoo to the Pathological Institute at the Veterinary University (Tierärztliche Hochschule) of Berlin, where it was dissected in order to ascertain its cause of

logistical arrangements. They often provide instructions for further use – ‘With a request for examination and transfer to the Zoolog. Museum on Invalidenstraße’, says one, for example. The first journey that an animal took after its death usually led from the zoo to the Pathological Institute at the Veterinary University (Tierärztliche Hochschule) of Berlin, where it was dissected in order to ascertain its cause of  death.2 After that, the Pathological Institute sent what remained of the carcass back to the zoo or forwarded it on at the zoo’s behest – to private taxidermists, or to scientific institutions such as the Anatomical Institute, the Zoological Institute of the Agricultural University, or the Zoological Museum at the university in Berlin.3 This kind of information can be put together like the pieces of a puzzle to map out a local network of relationships. Even though gaps remain, the tags help to identify the important actors who were involved in the further utilisation or disposal of zoo animals in Berlin in the early twentieth century.

death.2 After that, the Pathological Institute sent what remained of the carcass back to the zoo or forwarded it on at the zoo’s behest – to private taxidermists, or to scientific institutions such as the Anatomical Institute, the Zoological Institute of the Agricultural University, or the Zoological Museum at the university in Berlin.3 This kind of information can be put together like the pieces of a puzzle to map out a local network of relationships. Even though gaps remain, the tags help to identify the important actors who were involved in the further utilisation or disposal of zoo animals in Berlin in the early twentieth century.

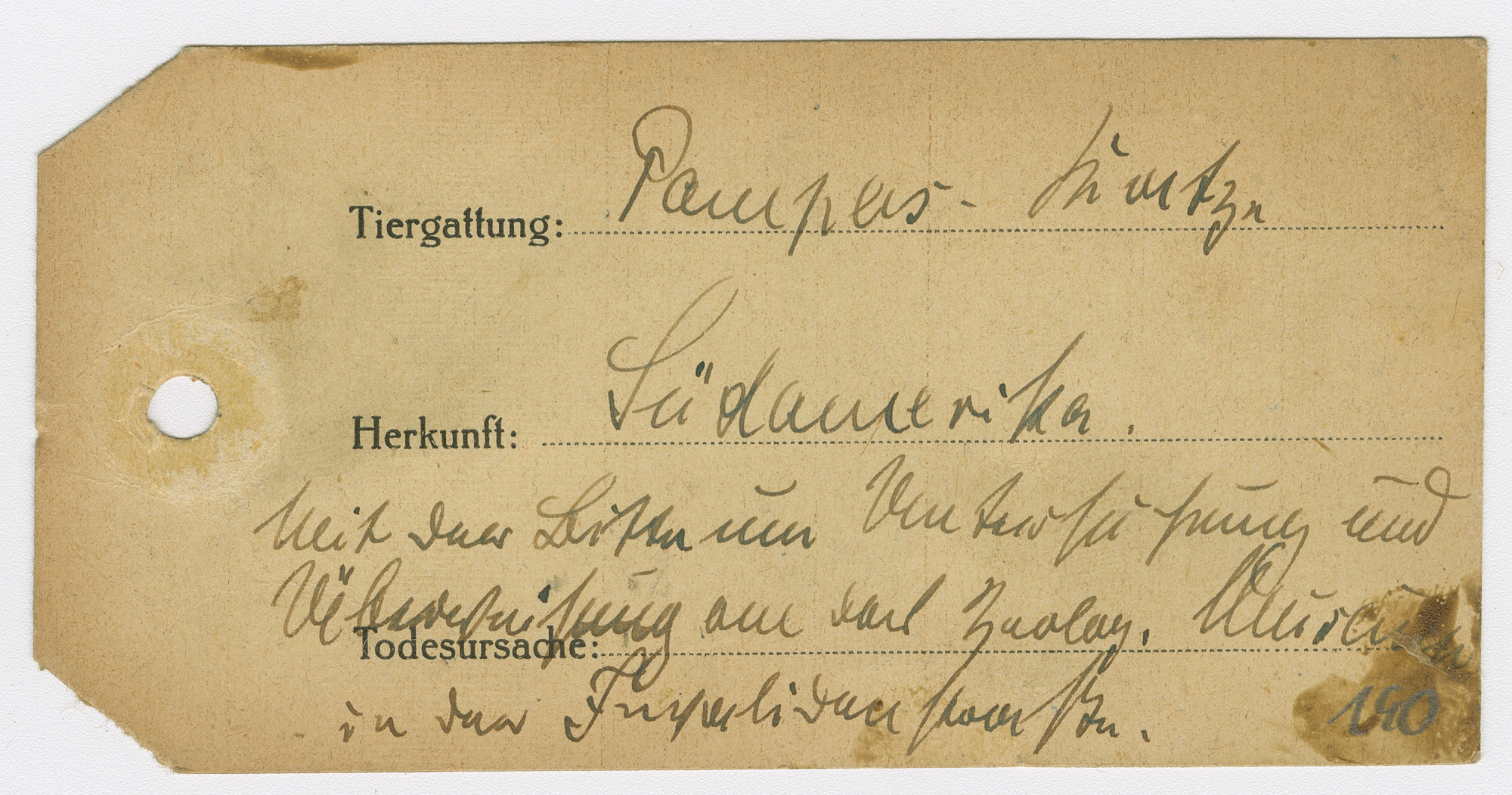

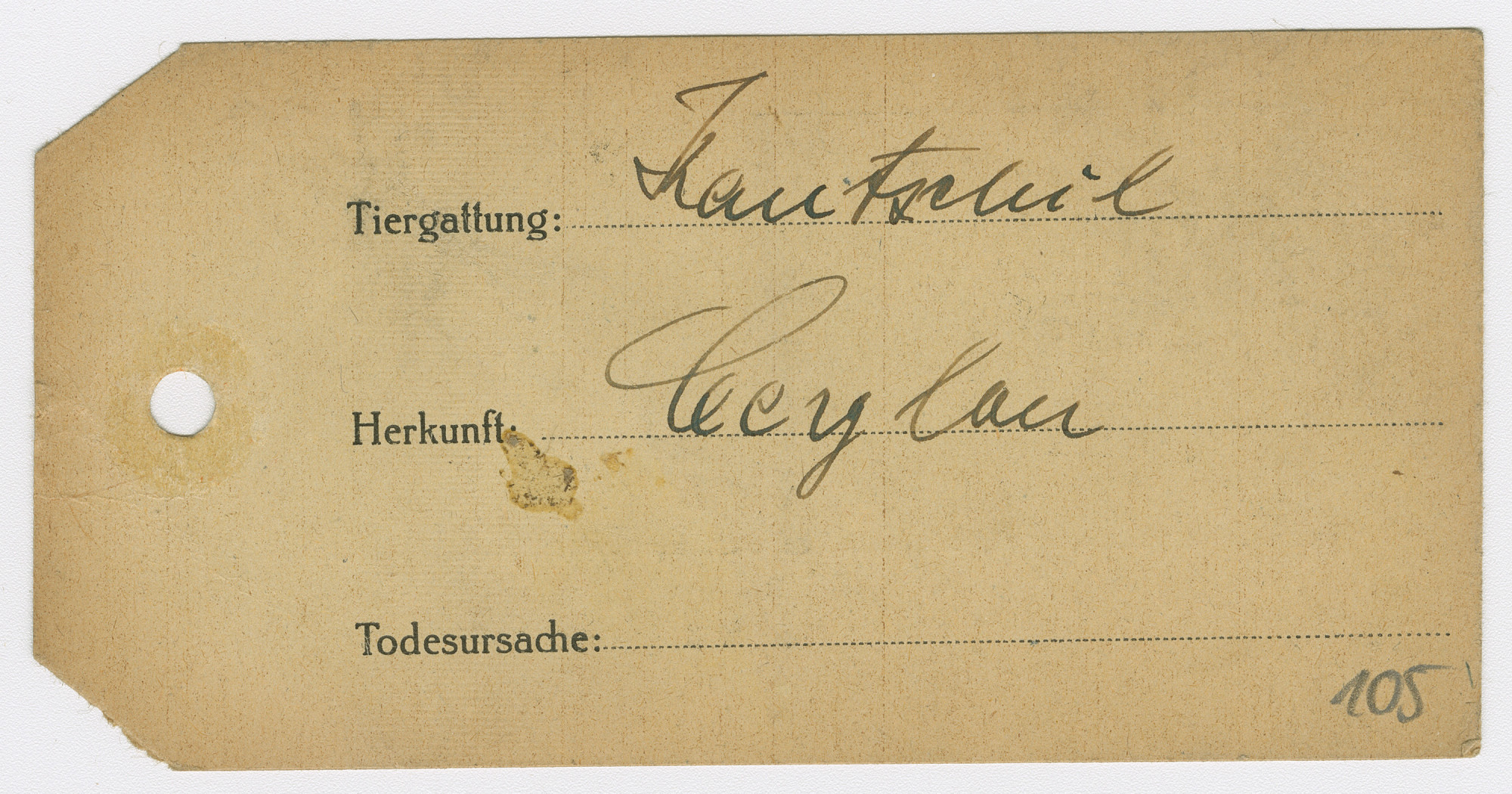

The back of a label could be used to convey information about the animal’s species, origin, and cause of death so that the museum could create a  record of the animal. Abyssinia, Ceylon, and South America frequently appear. The notes therefore do not just make a local network visible, but also point back to the

record of the animal. Abyssinia, Ceylon, and South America frequently appear. The notes therefore do not just make a local network visible, but also point back to the  global trade in animals and

global trade in animals and  animal catching, and names like Abyssinia and Ceylon make it clear that this was a colonial network.

animal catching, and names like Abyssinia and Ceylon make it clear that this was a colonial network.

Almost just as crucial as the information that appears on the labels is that which is not recorded. Detailed information like the kind noted on this label was the exception:

Knowledge thing: Label with detailed information about an animal delivery. (MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, Bl. 142 recto. All rights reserved.)4

Entries were frequently left  empty, or the information provided was very general.

empty, or the information provided was very general.

A knowledge thing with gaps: label with missing entries and general information about the animal delivery (MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, Bl. 024 recto; MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, Bl. 105 recto. All rights reserved.)5

These labels thus allow us to read not just the information that was sent to the museum but also the gaps in knowledge.6 These gaps point not least to the differences between  zoos and museums – the data collected by zoos was not necessarily as extensive or as precise as the data gathered by natural history collections. However, labels often provided additional instructions.

zoos and museums – the data collected by zoos was not necessarily as extensive or as precise as the data gathered by natural history collections. However, labels often provided additional instructions.

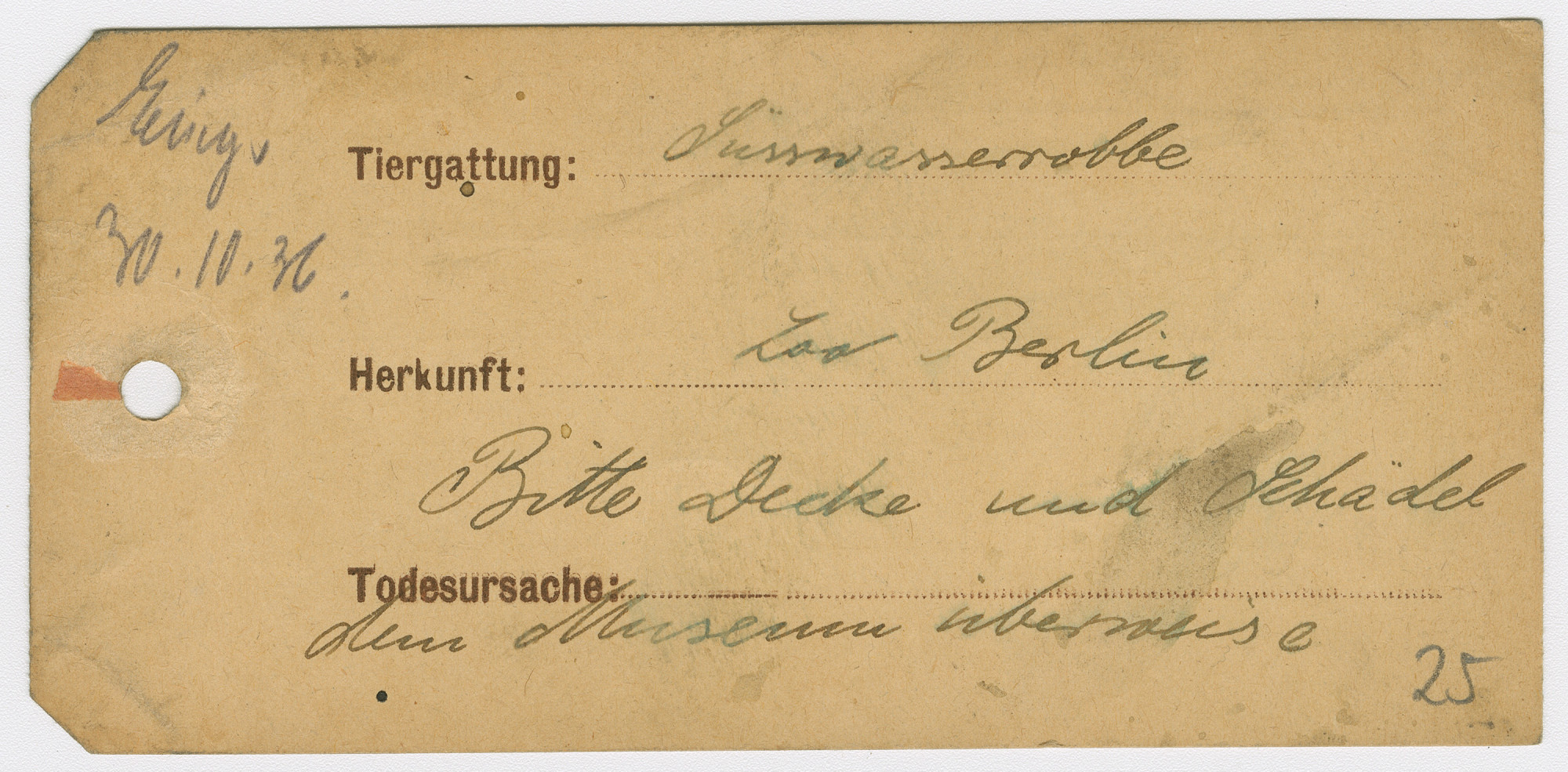

Labels as directions for use: these instructions show which body parts of an animal became collection items after its death. (MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05 Nr. 96, Bl. 125 recto. All rights reserved.)7

Instructions like ‘Please transfer hide and skull to museum’ provide clues about how objects were handled and what they were used for, i.e., about practices of use as they also appear in the  logbooks of the Zoological Museum, for instance. Here, too, there were delays, accidents, and misunderstandings. It is precisely incidents like these that tell us about the challenges that sometimes arose when an animal was being transferred from the zoo to the museum or being

logbooks of the Zoological Museum, for instance. Here, too, there were delays, accidents, and misunderstandings. It is precisely incidents like these that tell us about the challenges that sometimes arose when an animal was being transferred from the zoo to the museum or being  transformed from a live zoo animal into a museum specimen; about where knowledge was successfully transferred but also where information flows got bogged down.

transformed from a live zoo animal into a museum specimen; about where knowledge was successfully transferred but also where information flows got bogged down.

- Translation, label on top: ‘Forward to museum / To: Pathological Institute of the Veterinary University Berlin’; label below: ‘Animal species: [illegible]. / Origin: South-America. / With request for examination and transfer to the Zoolog. Museum on Invalidenstraße.’↩

- After the founding of the Free University of Berlin in 1960, the Veterinary Medicine Faculty of the university and the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) took over the task of performing necropsies.↩

- Cf. MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05, no. 97.↩

- Translation: ‘Animal species: [illegible]. / Origin: Patagonia. / Cause of death: inflammation of the bowel.’↩

- Tranlation, left: ‘Animal species: [illegible]. / Origin: From animal trade. / Cause of death: no entry’; right: ‘Animal species: [illegible]. / Origin: Ceylon. / Cause of death: no entry.’↩

- Of course, it could be that this information was delivered in the accompanying item lists or in correspondence (see for example MfN, HBSB, S004-02-05, no. 97); however, the fact that detailed information is entered on some labels seems to suggest that it was not provided in other cases.↩

- Translation: ‘Animal species: fresh water seal. / Origin: Berlin Zoo. / Cause of death: no entry. / Please transfer hide and skull to the museum.’↩