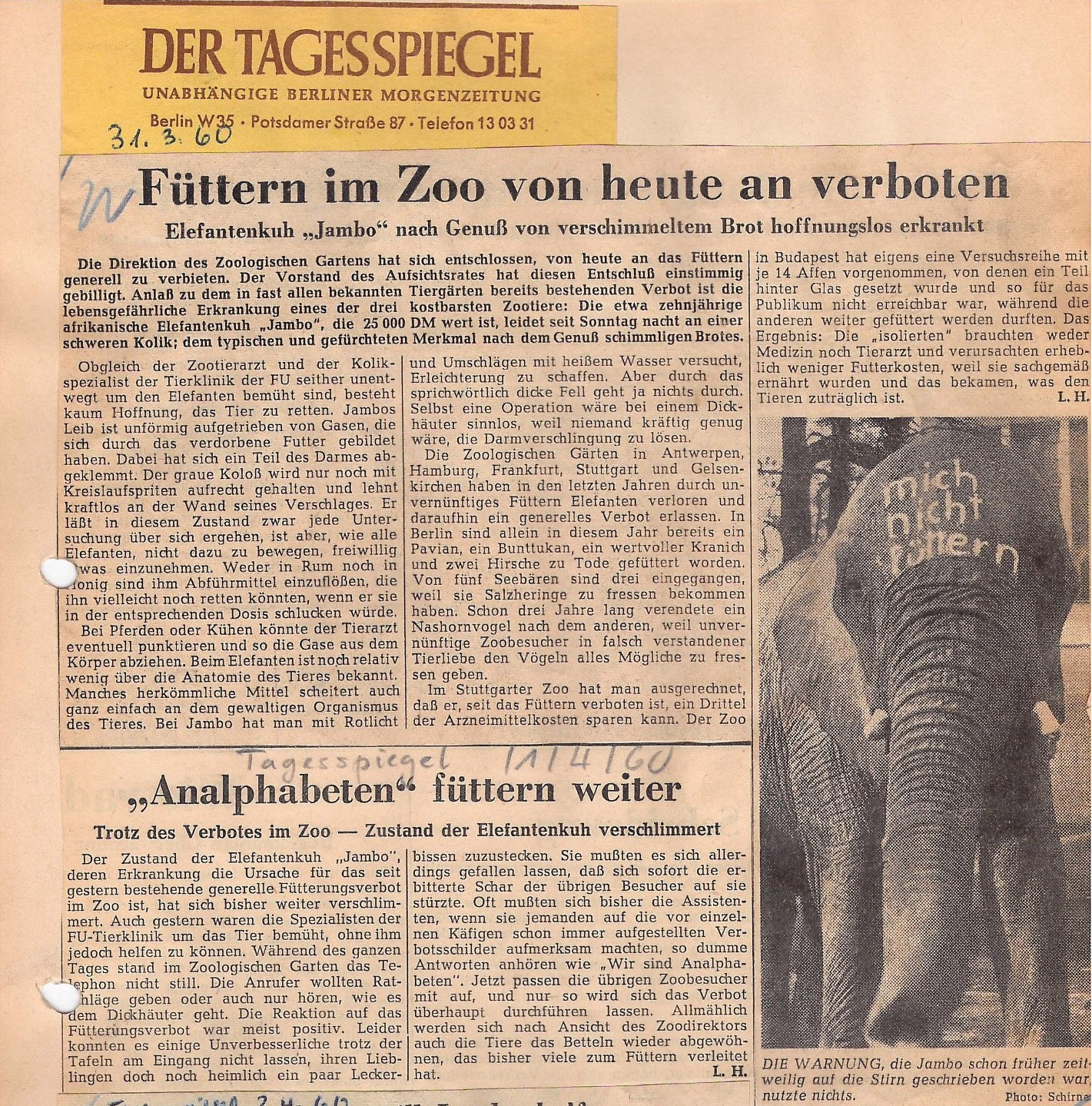

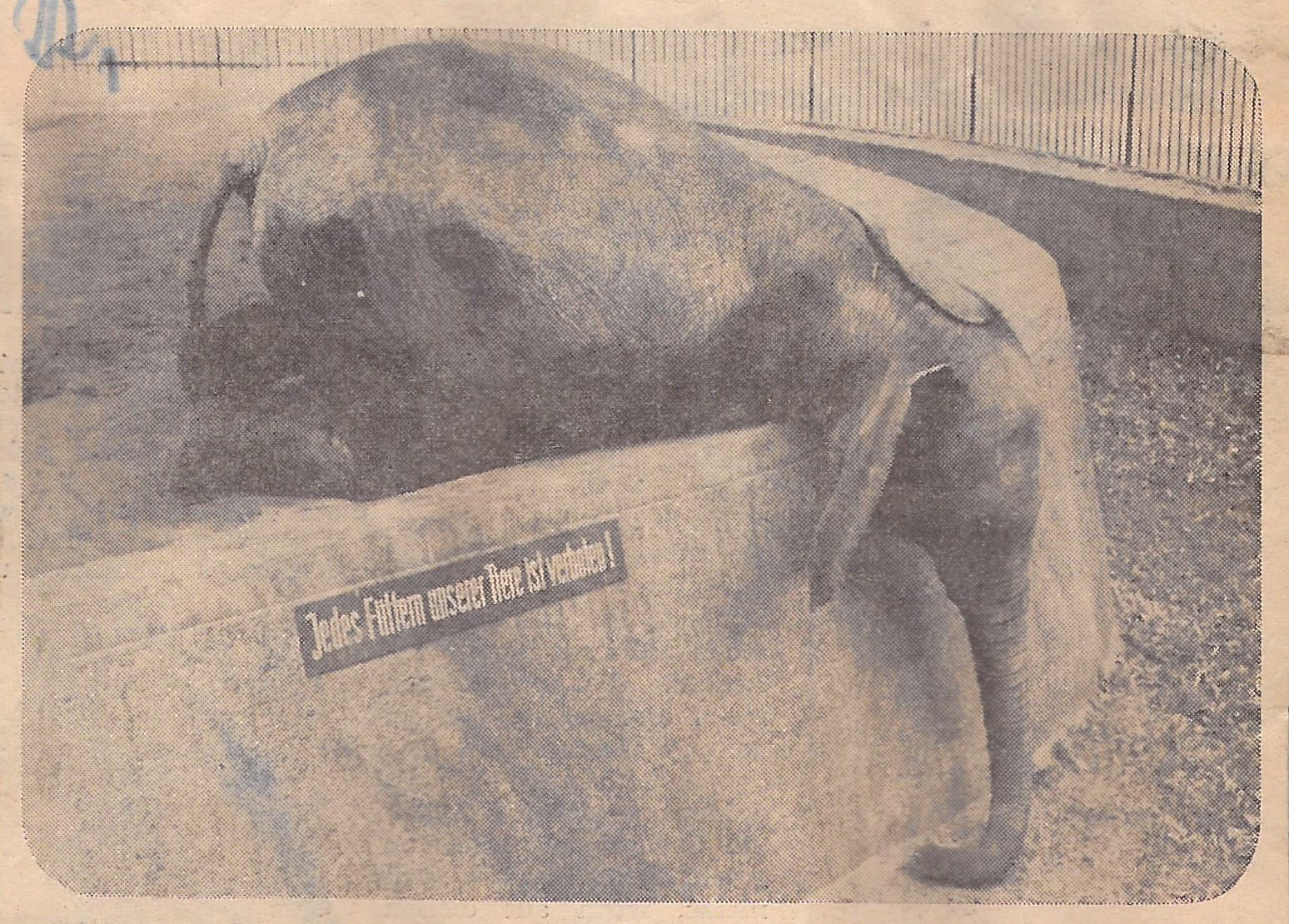

Article in the Tagesspiegel on the feeding ban at Berlin Zoo occasioned by “Jambo’s” illness, 31.03.1960.

In 1960, Berlin Zoo’s elephant cow “Jambo” fell ill due to overfeeding by visitors and eventually had to be put down. The elephant’s  death was followed by a heated debate centered on the proper care and feeding of animals in captivity. “Jambo’s” death led to a general ban on feeding the animals at Berlin Zoo from 10 April 1960.

death was followed by a heated debate centered on the proper care and feeding of animals in captivity. “Jambo’s” death led to a general ban on feeding the animals at Berlin Zoo from 10 April 1960.

The elephant’s death was not the first case of a zoo animal dying as a result of  overfeeding. Visitors giving zoo animals food they bring into the zoo is part of a long history of incorrect or excessive feeding. Visitors had essentially been permitted to feed the animals since zoological gardens were established in the 19th century. The zoo guidebooks of the time – small, printed pamphlets – invited visitors to feed the animals, but even then there were certain restrictions. In 1873, Berlin Zoo’s guidebook already advised visitors against feeding some animals, and as early as 1879, visitors to the Hamburg Zoological Garden were also “most humbly and urgently requested to feed only those animals whose names are displayed on the notice boards”.1 Just a few days after the opening of the Frankfurt Zoological Garden in 1858, reports stated that, “most of the animals have suffered from upset stomachs as a result of the excessive feeding by visitors”.2 In most zoos, it was strictly prohibited to feed particularly sensitive animal species such as apes, predators, and sea lions. Schönbrunn Zoo’s guidebook of 1912 also refers to signs on the cages warning visitors that feeding was not permitted.

overfeeding. Visitors giving zoo animals food they bring into the zoo is part of a long history of incorrect or excessive feeding. Visitors had essentially been permitted to feed the animals since zoological gardens were established in the 19th century. The zoo guidebooks of the time – small, printed pamphlets – invited visitors to feed the animals, but even then there were certain restrictions. In 1873, Berlin Zoo’s guidebook already advised visitors against feeding some animals, and as early as 1879, visitors to the Hamburg Zoological Garden were also “most humbly and urgently requested to feed only those animals whose names are displayed on the notice boards”.1 Just a few days after the opening of the Frankfurt Zoological Garden in 1858, reports stated that, “most of the animals have suffered from upset stomachs as a result of the excessive feeding by visitors”.2 In most zoos, it was strictly prohibited to feed particularly sensitive animal species such as apes, predators, and sea lions. Schönbrunn Zoo’s guidebook of 1912 also refers to signs on the cages warning visitors that feeding was not permitted.

From early on, zoos indicated, through guidebooks and signs, what could be given to the animals. Elephants, like monkeys, were particularly popular with zoo visitors, and Berliners could feed them bread, carrots, oranges, bananas, and lemons. In order to “steer the public’s tendency to feed the animals in the right direction”, when the monkey house was extended in 1925, contraptions into which food could be placed were installed and painted in red. The monkeys “had to use some intelligence” to get at the food. At the same time, a feed station was placed nearby, where “suitable feed” could be purchased. According to the zoo’s annual report, this was well received and also regulated feeding, at least to some extent.3

Discussions about visitor  feeding and partial bans in zoological gardens had been ongoing for some time, both in Germany and in other countries. Yet, the majority of zoos did not introduce a general feeding ban until the 1950s, after illness and death caused by overfeeding became more frequent, especially during the well-attended summer months. When a newly acquired elephant at Frankfurt Zoo died on 1 June 1953 as a result of overfeeding by visitors, the director at the time, Bernhard Grzimek, decided to impose a complete ban on the feeding of zoo animals by visitors. In 1957, Leipzig Zoo followed suit, as did the Münster Zoological Garden in 1959, after it too lost several animals.4 In the same year, the issue was also a topic of discussion at the annual meeting of the Association of German Zoo Directors (Verband Deutscher Zoodirektoren). The association decided in favor of a general ban on visitor feeding.

feeding and partial bans in zoological gardens had been ongoing for some time, both in Germany and in other countries. Yet, the majority of zoos did not introduce a general feeding ban until the 1950s, after illness and death caused by overfeeding became more frequent, especially during the well-attended summer months. When a newly acquired elephant at Frankfurt Zoo died on 1 June 1953 as a result of overfeeding by visitors, the director at the time, Bernhard Grzimek, decided to impose a complete ban on the feeding of zoo animals by visitors. In 1957, Leipzig Zoo followed suit, as did the Münster Zoological Garden in 1959, after it too lost several animals.4 In the same year, the issue was also a topic of discussion at the annual meeting of the Association of German Zoo Directors (Verband Deutscher Zoodirektoren). The association decided in favor of a general ban on visitor feeding.

Prohibition signs in zoological gardens, printed in 8-Uhr-Blatt, 13.04.1960.

However, the introduction of a general feeding ban was not without controversy, as is evident from press reports and letters to the zoos at the time. Since many zoo visitors had long been accustomed to feeding the animals, and the animals in turn expected food, the prohibition initially met with resistance in many places, from Frankfurt to Leipzig to Berlin.5 The example of Berlin reveals how lengthy and difficult it was to implement such a ban.

At first, the zoo hoped partial bans would be enough.

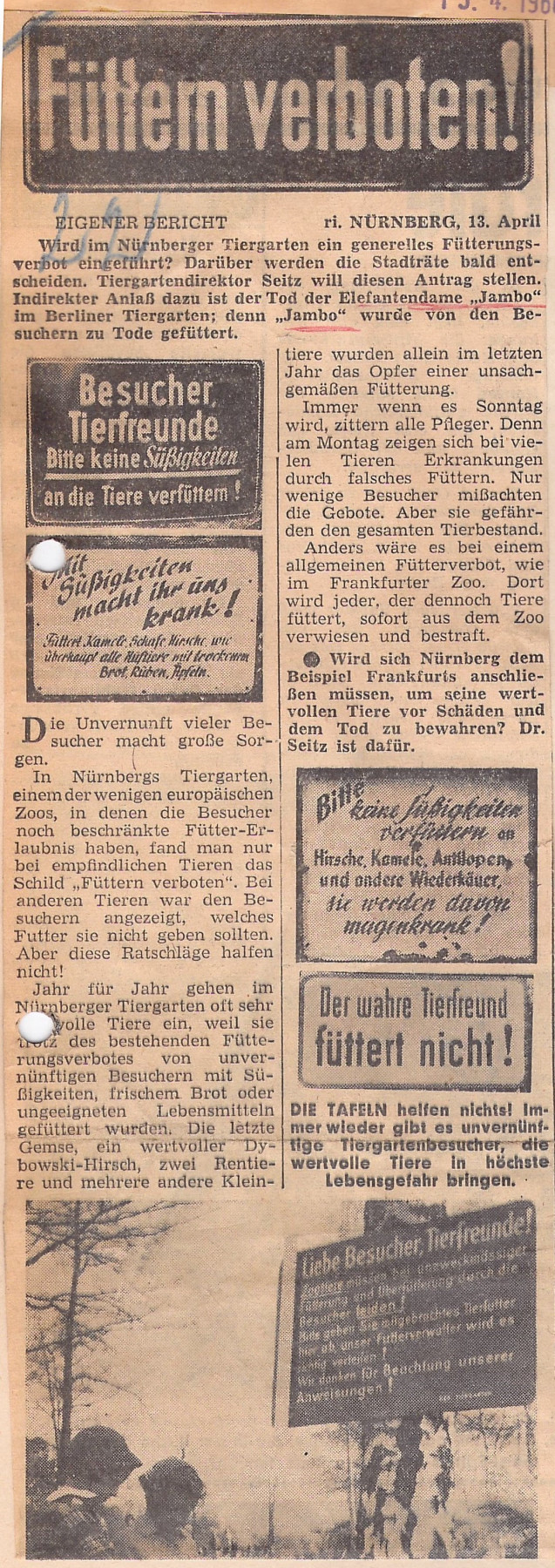

In as early as 1954, visitors to Berlin Zoo were already banned from feeding the giraffes. The sign and a barrier were meant to keep visitors at a distance. (AZGB, image: Ottmar Kränzlein. All rights reserved.)6

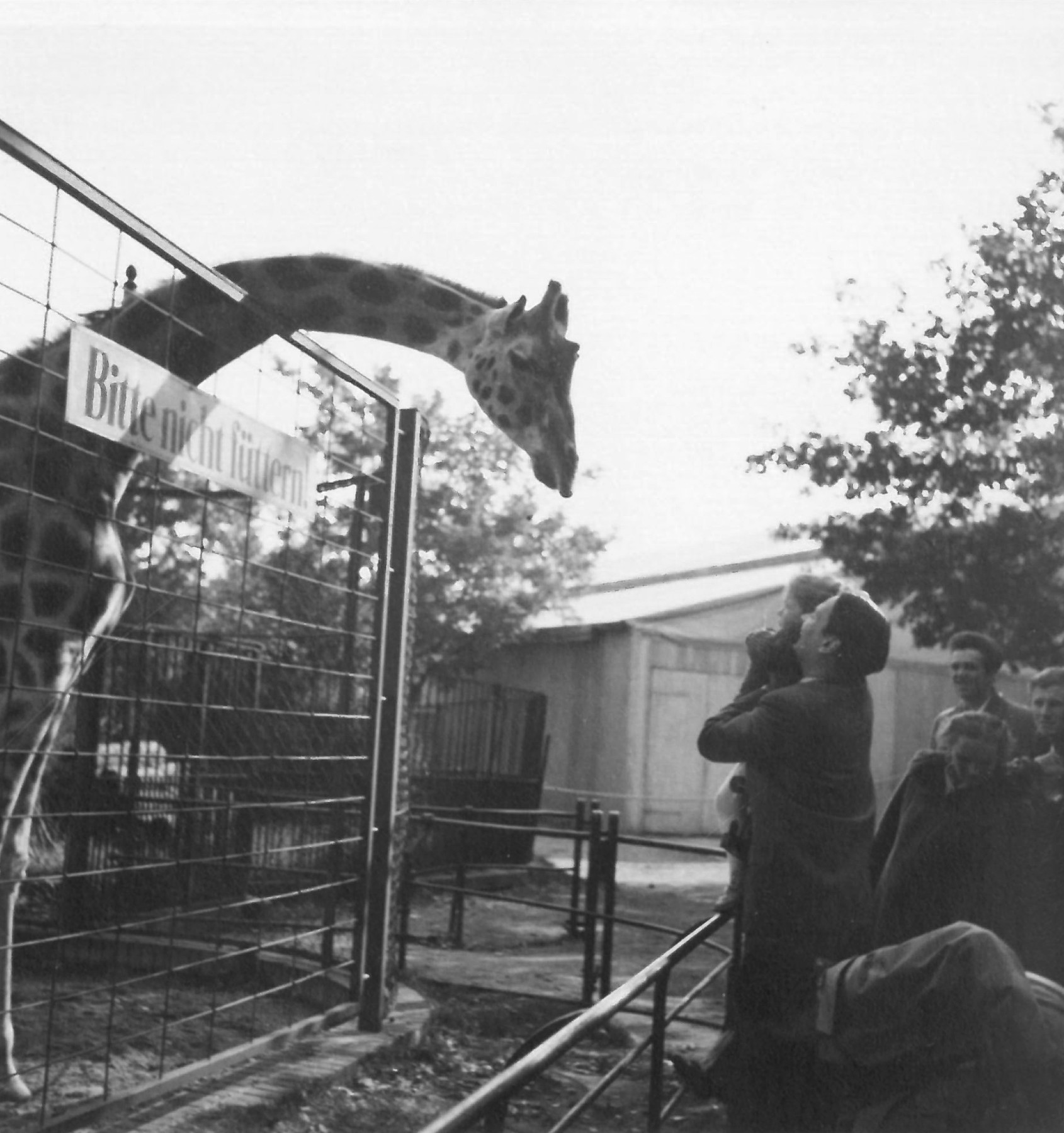

In 1960, Berlin Zoo’s General Guidelines for the Feeding of Animals by Visitors still stated:

“It is, however, essential that at least these partial prohibitions, which only affect particularly sensitive animal species, or only prohibit the use of harmful types of feed, are strictly adhered to. Wrong or excessive feeding has already led to severe health problems, breeding difficulties, and often even result in a painful end for many animals. We therefore urgently request that our visitors observe the following guidelines.”7

Responsibility was placed on the visitors, and the guidelines were still formulated as a request, a moral appeal. When shortly after this, the zoo decided to impose a general ban, this first had to be made public, enforced, and accepted. What is taken for granted today initially required detailed explanation:

“We hope you will understand that we have taken this measure in the interest of keeping our animals healthy. Please make sure you hand in any food you may have brought with you at reception, where it will be placed in the collection bins set up there. Given the significant increase in the number of visitors to our zoos nowadays, we can no longer subject the animals, which we have gone to great lengths to procure and rear, to well-intentioned but uncontrolled feeding by the public.”8

Increasing visitor numbers were not the only consideration being invoked. To fulfill its ambition to maintain species-appropriate animal husbandry, the zoo needed to ensure that the quantity and quality of feed were compatible with the feeding habits of the animals. It was precisely this awareness that needed to be communicated to the visitors:

“Even if your food seems fine to you, if too many people feed the animals, serious illness and death will continue to occur; even if only one in ten visitors were to offer a small amount of food, an enormous quantity would accumulate in the course of a day. An animal that is normally fed on hay and oats, for example, would be in mortal danger if it were suddenly given pounds of bread, fruit, and kitchen scraps during a busy day at the zoo. The view that ‘every animal knows what and how much is right for them’ is unfortunately mistaken, and many a zoo animal has met a painful end because of it.”9

The new guidelines overwrite the old ones in Berlin Zoo’s visitors guide from 1960.

After the decision was made to prohibit visitors from feeding the animals, the old feeding rules in the zoo guide of 1960 were initially temporarily overwritten with a red stamp. The regulations were completely revised the following year. From then on, the guidebook informed people of the feeding ban at the very start, in the “Gartenordnung” – the zoo regulations – or in the introduction. In the zoo itself, signs were also placed directly at the enclosures.

Sign prohibiting feeding at the Zoological Garden Berlin, 1969. (AZGB. All rights reserved.)

Sign at the emu enclosure at Berlin Zoo, 1980. (AZGB, image: Kühn. All rights reserved.)

To ensure that the feeding ban was observed, Frankfurt and Berlin Zoos handed out leaflets, and put up multilingual signs: “Feeding: DM 25 fine and admission ban”. East Berlin’s Tierpark also threatened to fine anyone feeding the animals. Visitors nevertheless repeatedly disregarded the ban, especially in its early days.10 The feeding prohibition epitomised a conflict of interest between species-appropriate animal husbandry, educational aims, and the demand for entertainment and direct contact with the animals. For the zoological gardens, animal wellbeing and not least economic considerations were also at stake. Elephants like “Jambo” were valuable animals, and their deaths were a correspondingly significant financial loss. The prohibition simultaneously resulted in savings in other departments: As the Tagesspiegel reported, the amount Stuttgart Zoo spent on medicine had fallen by a third since the introduction of a ban on feeding.11

The prohibition also changed the zoo visitors’ relationship to the animals. Berlin Zoo had to issue countless warnings and reprimands because visitors continued to feed the animals despite the ban. This debate was always emotional, because it brought the question of people’s love of animals (Tierliebe) to a head like no other subject at the time.

For a long time, and especially in the postwar years, being an animal lover meant expressing care for the animals  by feeding them.12 The feeding ban introduced a different understanding of what it meant to care for animals. This also changed, for example, the way

by feeding them.12 The feeding ban introduced a different understanding of what it meant to care for animals. This also changed, for example, the way  lion cubs were handled, and at the same time manifested in a different attitude toward people’s own animal feeding habits.

lion cubs were handled, and at the same time manifested in a different attitude toward people’s own animal feeding habits.

For many people, the best way to express their love of and care for animals was through restraint – secondary to their own desire to feed the animals. As an anonymous supporter of the ban put it in a letter to the zoo: “We too regret the sad end of Jambo and welcome the feeding ban. There is no other way to deal with Berliners and their excessive love of animals.”13 Where previously giving readily had been one of the main virtues of the “animal lover” at the zoo, now the health of the animals depended on self-control. Feeding – especially excessive feeding – was now judged to be a “false love of animals”.14 This was part of a broader change, which cultural studies scholar Christina Wessely describes as entailing a shift that sees the, at times quite pushy, animal lover increasingly adopting a view in which humans are very deliberately relegated to the background – a development that was, to a great extent, only completed around the turn of the millennium.15

Berlin Zoo also made use of the ‘love of animals’ rhetoric to implement its feeding ban in the 1960s. It relied not only on disciplinary measures in the form of prohibition signs, but also appealed to the visitor’s conscience:

“Real animal lovers can still be close to their favorite animals even without bags of sweets, and are happy when the animals no longer just stand begging at the bars all day, but rather lead healthy and carefree natural lives.”16

It was in fact the particularly tame animals, those accustomed to human beings and their feeding, that were especially at risk. In 1959, when feeding was still theoretically permitted, the zoo already “had to ban feeding for some very tame toucans during the Easter holidays”.17

The zoo also invoked people’s love of animals when it made a “special request” to its visitors, calling on them to actively participate in enforcing the zoo rules. This was already the case when partial bans were still in place:

“Special request: True animal lovers prove their love of animals by helping our officials make sure that no visitor disobeys the feeding ban for certain animals. It would be regrettable if the management were forced to issue a universal feeding ban in order to put a stop to unauthorised feeding.”

![Page 8 from an old zoo guide. Text: Which animals visitors are allowed to feed, and with what. [...] Please do not give the animals any spoiled food; it is extremely harmful! The same applies to unripe fruit. Please do not give the animals sugar or sweets; almost all animals like them, but if each visitor gives them just a little bit of sugar, it will amount to so much that the animals will become ill. Many zoo animals have died in this way. Do not feed: Predators (large or small), apes, seals, penguins, birds of prey and owls, antelopes and giraffes, some deer species, or ostriches. Framed at the very bottom is the aforementioned “special request”.](/images/mv/FuetterregelnWegweiser1956AusschnittJPG.jpg)

This appeal in the 1956 zoo guide was not yet a universal feeding ban, however. Visitors were still allowed to feed many of the animals with certain foods.

Many people took this request at its word, and so in the first months after the ban was introduced, the zoo received numerous letters like this one:

“[…] the love of animals prompts me to complain to you about what I experienced during my visit to the zoo last Saturday. A boy of about six years of age gave an elephant some poppcorn [sic]. He and his father did not understand when I pointed out the feeding ban; I heard them speaking English. But I think that even foreigners should know that we should not feed the animals. […] I want to bring this to your attention in the hope that perhaps you will see fit to levy a fine on such unreasonable people. I am by no means alone in my conviction that only a fine, and not simple requests and prohibitions, will be successful in the long run, for the good of our beloved animals.”18

Another anonymous writer told of three ladies she had observed at the elephant enclosure. “One of them kept on feeding, and when I angrily told her to stop, because there were signs everywhere, she became impertinent – I have a full belly, but the animals are hungry, and I should move along. And she threw in another whole toasted rusk.” The correspondent ended her letter with the words: “If you think it is good that this woman is allowed to feed the animals, then I never want to visit the zoo again. […] An animal-loving zoo visitor.”19

These and other incidents further fuelled the discussion about how best to put the feeding ban into practice. Suggestions from the public ranged from the introduction of guards, to imposing fines on transgressors, and expelling them from the zoo.

Other suggestions were focused on changing the architecture, instead of disciplining people:

“Wouldn’t it be appropriate”, wrote one visitor after the death of an elephant seal, “to put mesh screens all around and on top of the enclosures, or to surround the pools with windows and put wire mesh on top, so that it is impossible to stick even the smallest thing through? Feeding bans are pointless; the animals must rather be shielded in such a way that deaths and illness no longer occur.”20

The architecture of the enclosures did indeed play an important role in the relationship between visitors and animals. In the early 1930s, the fences of many pens were replaced by trenches in the style of Hagenbeck’s open-air enclosures. The Berlin Zoological Garden, too, boasted about “de-fencing” its enclosures in 1930.21 However, the distance created by these measures did not necessarily completely cut off contact – nor was it the intention that it should do so. Rather, the trench in Berlin’s elephant enclosure was so narrow that, as zoo director Lutz Heck described “the animals could take bread from the visitors’ hands with their trunks”.22 As a photograph from the illustrated magazine Die Woche im Bild shows, the hippopotamus pool also still allowed close contact, enabling the visitors to continue feeding the animals.

The cover picture of Die Woche im Bild shows the hippopotamus pool, illustrating that feeding the animals had been one of the zoo’s main attractions for a long time, supported by architecture that allowed people to get close to the animals, 07.08.1930.

By the end of the 1950s, this was no longer an option. The food brought in by visitors was collected at the elephant enclosure.

After “Jambo” fell ill, visitors had to hand over the food they had brought with them to the zookeepers, as reported by the Bild-Zeitung, 02.04.1960.

In the early 1960s, the design of the new monkey house even incorporated  glass panels. Up till then, visitors had been able to feed the monkeys – with the exception of the apes – bread, tropical fruit, various vegetables, nuts, oatmeal and lentils.23 At one time, popcorn was even allowed – in the year the zoological garden opened a popcorn stand.24

glass panels. Up till then, visitors had been able to feed the monkeys – with the exception of the apes – bread, tropical fruit, various vegetables, nuts, oatmeal and lentils.23 At one time, popcorn was even allowed – in the year the zoological garden opened a popcorn stand.24

When the general ban on feeding came into effect in 1960, the guidelines for the monkeys, and later the architecture of the enclosure, also changed – for reasons of hygiene and safety. The change altered the balance between proximity and distance. Some visitors wrote letters in favor of this, but there were also those who were opposed to it. Zoo visitor Erna von Bongart, for example, wrote that she felt the monkeys

“[…] such as little Bubi, who have been in close contact with regular zoo visitors for many years, should not be cut off so completely. […] I don’t think it’s right to impose such strict measures of isolation on animals that have been used to human contact for all these years. Also, we should not forget how many lonely people there are; this also deprives them of a part of their purpose in life, of their joy.”25

The zoo’s management and staff themselves at first also seemed torn. According to director Heinz-Georg Klös, a public zoo was “there for the animals and the people”, which meant that compromises had to be made. “If, for example, the animals are ‘barricaded’ too much behind glass, bars, and barriers, the visitor – apart from not being allowed to feed them – misses out on the hands-on experience, the contact.” At the same time, Klös wrote in a reply to a letter from a zoo visitor: “[W]e will gradually put our most valuable animals behind glass. This will prevent unauthorized feeding, as well as the transmission of any diseases from the visitors to the animals.”26 Should the visitors themselves be responsible for drawing boundaries, limiting contact, and creating distance or should this be achieved by means of equipment and architecture?

Although zoo directors had been discussing the issue for some time, at the 40th Conference of Central European Zoological Gardens in 1928, “[e]very discussion on the use of glass walls to separate the monkeys from the public” still failed to produce “a unanimous response”.27 With the gradual shift toward  enclosure architecture that prevented direct contact, animals and visitors were separated. The change reduced the contact with the animals to eye contact and put a definitive end to feeding by visitors.28 This proved beneficial to the health of many animals, as within a few years of introducing the general ban on feeding, the zoo’s medication and treatment requirements decreased noticeably.29 Glass panels separating visitors from the animals were already put to use in the ape house in the early 1960s – a practice that is now widespread.30 At the same time, food preparation in the feeding kitchens was made accessible: “Large windows allowed the public to see into the feeding kitchen and watch the keepers prepare the feed […].”31 When in the mid-1970s, following the renovations to the ape house, the monkey house was refurbished, there, too, the animals were separated from the public by glass panels instead of iron bars. This also allowed for a clearer view, and direct eye contact. The behavior of many animals began to normalise; they no longer begged for food when a human approached. Zoo directors reported that fewer animals suffered, or died, from digestive disorders.32 “It is a pleasure to observe the natural behavior and playfulness of the animals since the introduction of the feeding ban”,33 one anonymous visitor wrote in a letter to Berlin Zoo. There were many approving voices like this one. It is interesting to note that, due to the newly imposed distance, many of the visitors who wrote in identified the zoo as a natural environment, and no longer regarded the animals begging for food as natural behavior. This reveals just how much notions of the ‘natural’ have changed over the years.

enclosure architecture that prevented direct contact, animals and visitors were separated. The change reduced the contact with the animals to eye contact and put a definitive end to feeding by visitors.28 This proved beneficial to the health of many animals, as within a few years of introducing the general ban on feeding, the zoo’s medication and treatment requirements decreased noticeably.29 Glass panels separating visitors from the animals were already put to use in the ape house in the early 1960s – a practice that is now widespread.30 At the same time, food preparation in the feeding kitchens was made accessible: “Large windows allowed the public to see into the feeding kitchen and watch the keepers prepare the feed […].”31 When in the mid-1970s, following the renovations to the ape house, the monkey house was refurbished, there, too, the animals were separated from the public by glass panels instead of iron bars. This also allowed for a clearer view, and direct eye contact. The behavior of many animals began to normalise; they no longer begged for food when a human approached. Zoo directors reported that fewer animals suffered, or died, from digestive disorders.32 “It is a pleasure to observe the natural behavior and playfulness of the animals since the introduction of the feeding ban”,33 one anonymous visitor wrote in a letter to Berlin Zoo. There were many approving voices like this one. It is interesting to note that, due to the newly imposed distance, many of the visitors who wrote in identified the zoo as a natural environment, and no longer regarded the animals begging for food as natural behavior. This reveals just how much notions of the ‘natural’ have changed over the years.

- Edwin Hennings. Katalogirter Führer durch den Berliner Zoologischen Garten, 6. Ed. Berlin: A. Seidel, 1873: 2. The Hamburg Zoo guide explicitly referred to the signs. Cf. Heinrich Bolau. Führer durch den Zoologischen Garten zu Hamburg, 29. Ed. Hamburg: Verlag der Zoologischen Gesellschaft Hamburg, 1879: n.p.↩

- D. Backhaus. “Die Eröffnung des Gartens im Jahre 1858”. In Hundertjähriger Zoo in Frankfurt am Main. The Zoological Garden of the City of Frankfurt am Main (ed.). Frankfurt a.M.: 1957.↩

- Actien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin. Geschäftsbericht für das Jahr 1925. Berlin: 1926.↩

- At the beginning of 1956, a report in the Leipziger Volkszeitung informed readers of the introduction of a general ban on feeding: “Most of the treats brought by the public for their favorite animals are unsuitable for the animals, in many cases even harmful. […] Often, nausea and intestinal diseases set in, and they require medical treatment to cure their upset stomachs. Unfortunately, this does not always go smoothly, and we have already lost valuable animals in this way. In the interest of keeping our wards healthy, improper feeding must be avoided.” Dittrich, Lothar. “Nicht mehr füttern!”. Leipziger Volkszeitung, January 1956, cited in: Mustafa Haikal and Jörg Junhold. Auf der Spur des Löwen: 125 Jahre Zoo Leipzig. Leipzig: Pro Leipzig e.V., 2003: 181.↩

- Conference of the Association of German Zoo Directors from 18 to 20 June 1959. Minutes of the business sessions, AZGB V 1/4; Benjamin Lamp. Entwicklung der Zootiermedizin im deutschsprachigen Raum. Giessen: VVB Laufersweiler, 2009: 178.↩

- In the Berlin Zoo guidebook, giraffes are first mentioned in the feeding guidelines in 1956 with the instruction that it is generally forbidden to feed them.↩

- Heinz-Georg Klös. Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin 1960. Berlin: Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1960.↩

- Heinz-Georg Klös. Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin 1961. Berlin: Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1961.↩

- Ibid. About ten years later, this was well-established and the guide simply noted: “Feeding is strictly prohibited. With around 2.5 million visitors a year, if everyone gave even a small morsel, such large quantities of food would accumulate that the animals would suffer harm. Well-intentioned but uncontrolled feeding can even result in death.” Heinz-Georg Klös. Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin 1975. Berlin: Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1975.↩

- Cf. for instance anonymous letter to the management of the Zoological Garden Berlin, 08.08.1966, AZGB O 0/1/224; H. Gottheim to the management of the Zoological Garden Berlin, 16.04.1960, AZGB O 0/1/112; Zoological Garden Berlin to M. Hingst, 20.07.1960, AZGB O 0/1/112; C. Hübner to the management of the Zoological Garden Berlin, no date, AZGB O 0/1/112; Management of the Zoological Garden Berlin to C. Hübner, AZGB O 0/1/112.↩

- “Füttern im Zoo von heute an verboten”. Tagesspiegel, 31.03.1960.↩

- On the figure of the ‘Tierfreund’, cf. Christina Wessely. Löwenbaby. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, 2019; Nastasja Klothmann. Gefühlswelten im Zoo: Eine Emotionsgeschichte 1900-1945. Bielefeld: transcript, 2015: 201-220.↩

- Anonymous letter to the management of the Zoological Garden Berlin, 11.04.1960, AZGB O 0/1/112.↩

- Cf. “Falsche Tierliebe”. Gießener Anzeiger, 16.04.1960.↩

- Wessely, 2019: 59.↩

- Klös, 1961: 8.↩

- Zoological Garden Berlin to M. Günther, 06.04.1959, AZGB O 1/2/80.↩

- M. Hingst to the Zoological Garden Berlin, 12.07.1960, AZGB O 1/2/81.↩

- Anonymous letter to the management of the Zoological Garden Berlin, 08.08.1966, AZGB O 0/1/224.↩

- A. Irmler to Heinz-Georg Klös, 21.09.1959, AZGB O 1/2/80.↩

- H. Beatz “Der Zoo wird entgittert”. Morgenpost Berlin, 22.02.1930. This shift was an international phenomenon. In London Zoo for instance, the biologist Julian Huxley, who became zoo director in 1936, advocated for dismantling fences.↩

- Lutz Heck. Führer durch den Zoologischen Garten zu Berlin 1931, Berlin: Actien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1931: 5.↩

- Lutz Heck. Wegweiser durch den Zoologischen Garten Berlin. Berlin: Actien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1936.↩

- Cf. Katharina Heinroth. Der Zoologische Garten Berlin: Zweiter Bericht und Wegweiser nach dem Kriege 1956. Berlin: Aktien-Verein des Zoologischen Gartens Berlin, 1956: 8.↩

- E. von Bongardt to the Management of the Zoological Garden Berlin, 01.10.1959, AZGB O 1/2/81.↩

- H.-G. Klös to C. Hübner, 13.05.1959, AZGB O 1/2/80.↩

- 40th Conference of Central European Zoological Gardens in Breslau from 23 to 25 August 1928, AZGB V 1/10.↩

- Exceptions today are petting zoos. Formerly, this was done by “Tierkinderzoos”.↩

- Cf. for instance Christoph Scherpner. Von Bürgern für Bürger: 125 Jahre Zoologischer Garten Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt a.M.: Zoologischer Garten, 1983: 145.↩

- Cf. Christina May. Die Szenografie der Wildnis: Immersive Techniken in zoologischen Gärten im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert. Berlin: Neofelis Verlag, 2020.↩

- Heinz-Georg Klös and Ursula Klös. Der Berliner Zoo im Spiegel seiner Bauten, 1841-1989: Eine baugeschichtliche und denkmalpflegerische Dokumentation über den Zoologischen Garten Berlin. Berlin: Heenemann, 1990: 237.↩

- Conference of the Association of German Zoo Directors from 18 to 20 June 1959. Minutes of the business sessions, AZGB V 1/4.↩

- Cf. Anonymous letter to the management of the Zoological Garden Berlin, September 1960, AZGB O 0/1/224; Scherpner, 1983: 145.↩