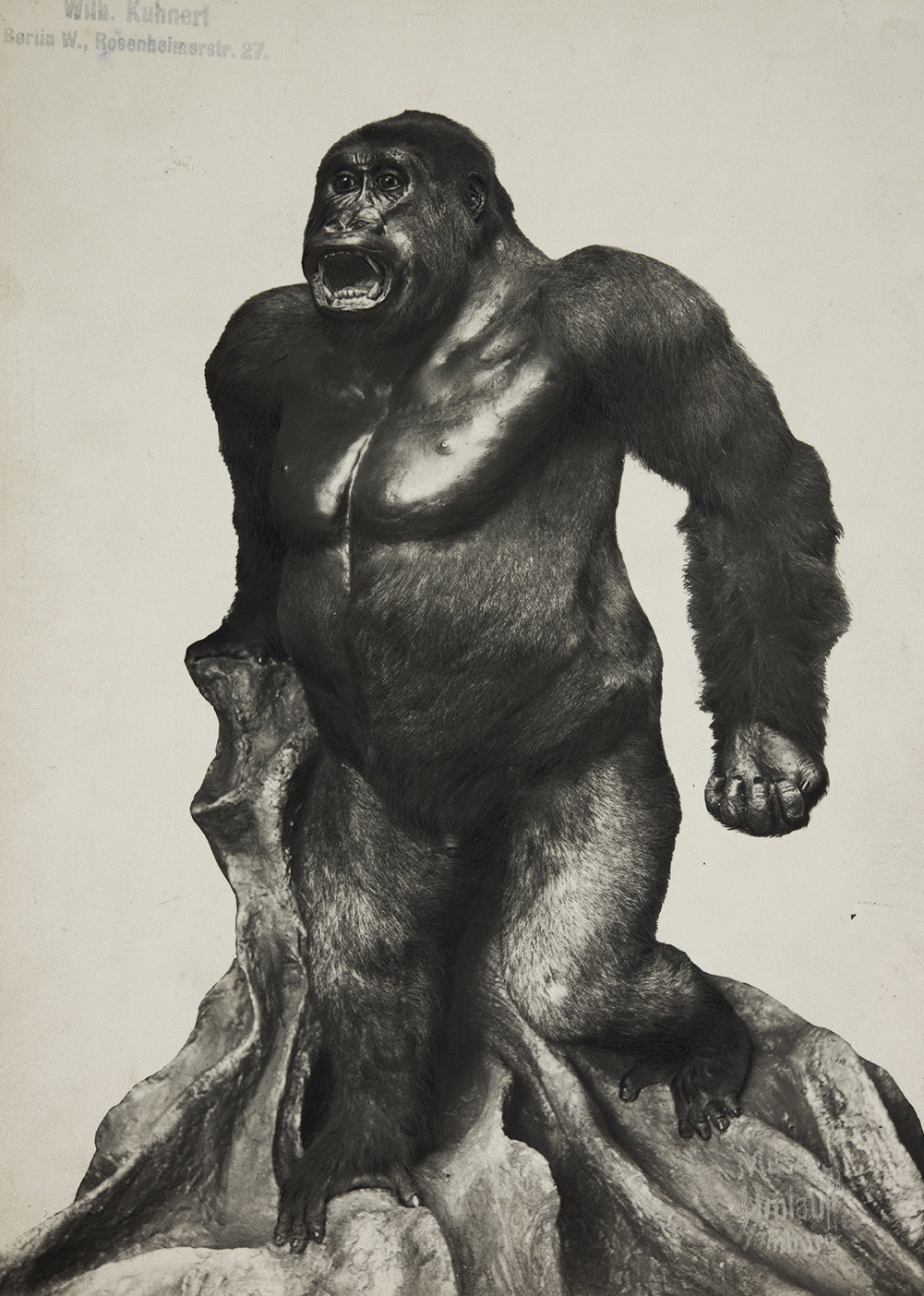

The ‘giant gorilla’1 dermoplastic taxidermy mounted by the Hamburg company Umlauff in 1901; postcard with the stamp ‘Wilh. Kuhnert’. (MfN, HBSB, ZM-B-IV-0872. All rights reserved.)

In 1903 at the German Colonial Hunting Exhibition held near Karlsruhe, Hamburg company J.F.G. Umlauff presented a selection of ethnographica from the German colonies as well as a number of  hunting trophies. In their Africa section, they began by displaying a photo of a ‘giant gorilla’ (Riesen-Gorilla) taxidermy that had been prepared in 1901 together with four real gorilla skulls. During the exhibition, they were able to supplement these exhibits with a dermoplastic taxidermy of another gorilla that had been ordered specially for the hunting exhibition – using a technology that pulls the animal’s real skin over a plastic replica. It was an exhibit of a new “giant gorilla” that had been brought “to Europe as the second fully grown specimen”,2 as the Deutsche Kolonial-Zeitung (German Colonial Newspaper) reported. Both dermoplastic specimens, mounted in 1901 and 1903 respectively, presented the gorilla as a ‘beast’, as a savage, threatening animal – following in the footsteps of an iconography that had been established in the late 19th century, creating an antithesis to depictions of gorillas as peace-loving, social animals that still persists today.

hunting trophies. In their Africa section, they began by displaying a photo of a ‘giant gorilla’ (Riesen-Gorilla) taxidermy that had been prepared in 1901 together with four real gorilla skulls. During the exhibition, they were able to supplement these exhibits with a dermoplastic taxidermy of another gorilla that had been ordered specially for the hunting exhibition – using a technology that pulls the animal’s real skin over a plastic replica. It was an exhibit of a new “giant gorilla” that had been brought “to Europe as the second fully grown specimen”,2 as the Deutsche Kolonial-Zeitung (German Colonial Newspaper) reported. Both dermoplastic specimens, mounted in 1901 and 1903 respectively, presented the gorilla as a ‘beast’, as a savage, threatening animal – following in the footsteps of an iconography that had been established in the late 19th century, creating an antithesis to depictions of gorillas as peace-loving, social animals that still persists today.

In 1901, the ethnographica and natural history dealer Umlauff had helped to shape this spectacular presentation form after buying off a boat the skin and skeleton of a gorilla shot during a hunt in Cameroon by Hans Paschen, a colonial officer.

While he was preparing the taxidermy – which was accompanied by a sales brochure about the ‘giant gorilla’, a hunting report, and a number of photos – Wilhelm Umlauff was guided by iconography of the gorilla as a ‘beast’ that had already been circulating.3 This iconography harked back to travel reports from the 18th and 19th centuries that portrayed the large primates as savage nemeses that could raise themselves up onto their hind legs and were superior to their hunters in terms of both size and strength. However, because the animals only raise themselves up onto two legs for short periods of time in the wild, the preparator took some poetic license: he leaned the gorilla’s arm on a tree root so that he could show the animal at its full height, towering over the human being. It was on this physical superiority that fantasies about gorillas preying on and raping human women were based. Because their upright gait was also seen to indicate their similarity to humans, the question hotly discussed in both science and popular science of whether primates and humans descended from a shared ancestor resounded in depictions of the primate standing on two legs. The collective projection addressed the missing link in this chain of descent, which could potentially be produced by crossing a human and a primate. The gorilla thus did not just embody man’s savage, animalistic, unsocialised adversary as a symbol of difference but also marked the question of potential kinship, considered scandalous to human identity. Unlike earlier taxidermies, where animals’ skins were simply stuffed, the new dermoplastic taxidermy technology allowed for the gorilla’s posture and even its facial expressions to be modelled and shaped to make the desired impact. The photo of the taxidermy illustrates how the gorilla was presented as a  savage and dangerous animal.

savage and dangerous animal.

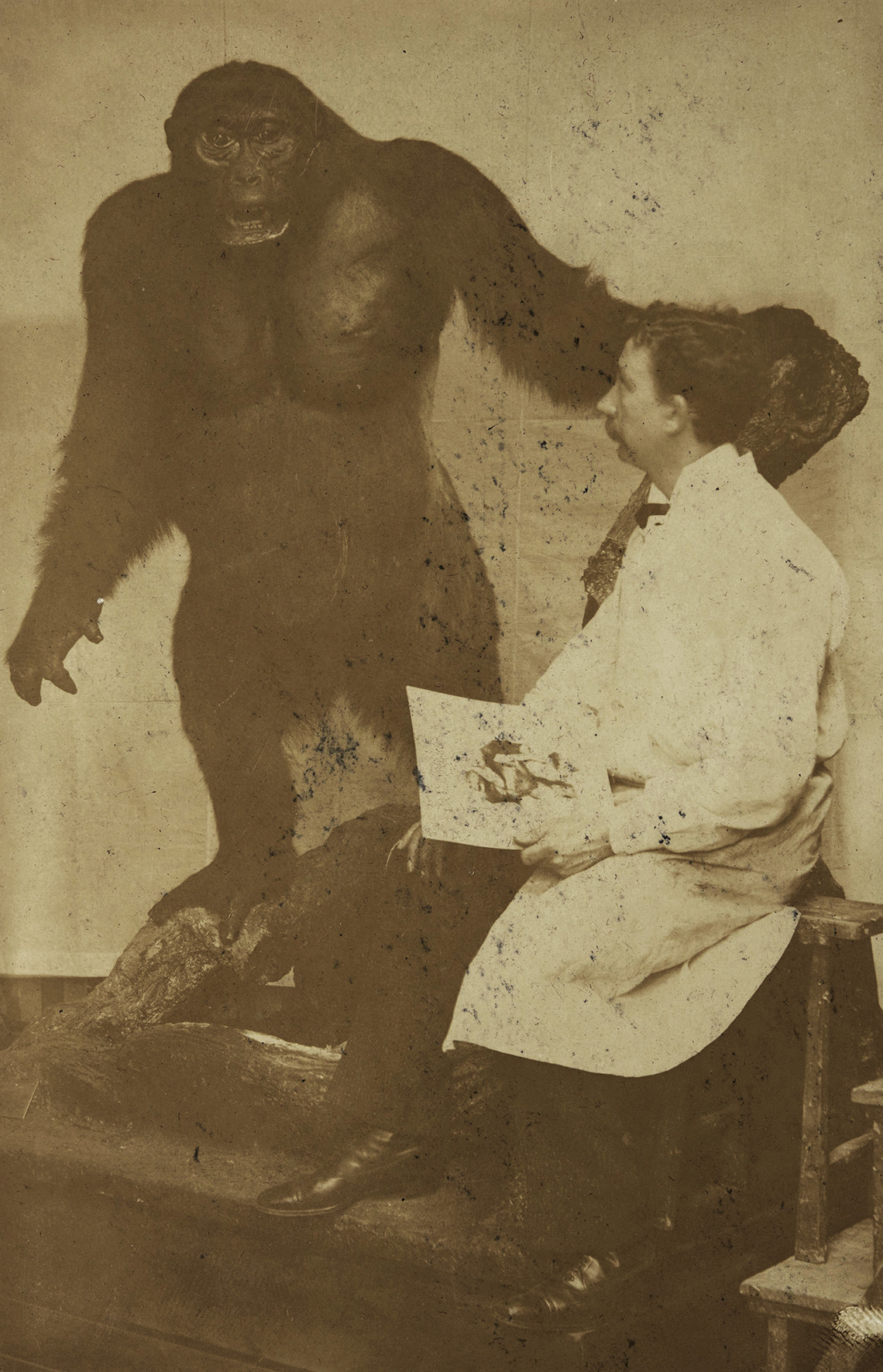

The taxidermist Wilhelm Umlauff, probably with a picture by Paul Matschie in his hand, beside the taxidermy of a gorilla for the 1903 Karlsruhe Colonial Hunting Exhibition. (MfN, HBSB, ZM-B-IV-0878-r).

At the same time, counter-images were already emerging, creating an iconography of the gorilla as a peaceful animal. After arriving alive at Berlin Aquarium in 1876, where he only survived for a year, it was “Mpungu” the gorilla who paved the way in Germany. While the emphasis on the animal’s peaceful characteristics would later be continued with the famous zoo gorilla  “Bobby”,4 Umlauff decided to go with his more sensational iconography in 1901, probably for sales reasons. Shortly before the exhibition in Karlsruhe opened, the company received the skin and skeleton of a second gorilla from Paul Matschie, curator of the Mammals Collection at the Berlin Zoological Museum and member of the Karlsruhe exhibition committee. The gorilla had been killed by Georg Zenker, a farmer and collector living in colonised Cameroon. To mount the dermoplastic taxidermy, Wilhelm Umlauff used sketches and photos that he had Matschie send to him as a guide. One surviving photo shows the taxidermist wearing a white lab coat, sitting beside his work, with the painted templates in his hand, underlining his artistic aspirations. “The gorilla steps down from a tree root; in his left arm he holds onto a tree trunk, while the right is at half-lowered. He is only 5cm smaller than the first.”5 Like the first, the second ‘giant gorilla’ was thus also mounted in an upright position for the Karlsruhe exhibition in order to impactfully present its size and savagery.6 After seeing photos of the animal mounted for the show, the hunter Georg Zenker commented in a letter to Umlauff that “his facial expressions” were unfortunately “not savage enough”, because, in reality, it had looked very different:

“Bobby”,4 Umlauff decided to go with his more sensational iconography in 1901, probably for sales reasons. Shortly before the exhibition in Karlsruhe opened, the company received the skin and skeleton of a second gorilla from Paul Matschie, curator of the Mammals Collection at the Berlin Zoological Museum and member of the Karlsruhe exhibition committee. The gorilla had been killed by Georg Zenker, a farmer and collector living in colonised Cameroon. To mount the dermoplastic taxidermy, Wilhelm Umlauff used sketches and photos that he had Matschie send to him as a guide. One surviving photo shows the taxidermist wearing a white lab coat, sitting beside his work, with the painted templates in his hand, underlining his artistic aspirations. “The gorilla steps down from a tree root; in his left arm he holds onto a tree trunk, while the right is at half-lowered. He is only 5cm smaller than the first.”5 Like the first, the second ‘giant gorilla’ was thus also mounted in an upright position for the Karlsruhe exhibition in order to impactfully present its size and savagery.6 After seeing photos of the animal mounted for the show, the hunter Georg Zenker commented in a letter to Umlauff that “his facial expressions” were unfortunately “not savage enough”, because, in reality, it had looked very different:

“ […] its jaws opened wide, its eyes staring, its hair ruffled, half standing, etc. I can’t even describe to you how savage such a fellow looks when he is in danger. […] My ears are ringing even today, and when I think about it, I’m still glad that everything went as smoothly as it did; and I am now sorry that I did not describe it to you more precisely before.”7

The hunting report did not just make use of the horror motif familiar from earlier texts of its kind but also allowed the hunter himself to appear as the hero.

So, while Zenker did not believe that the dermoplastic taxidermy had appropriately captured the gorilla’s ‘savagery’, its parameters – staring eyes, jaws open wide, bared teeth – were reproduced in a poster that Umlauff had reprinted for the Karlsruhe exhibition – presumably to increase sales – but which probably did not reach Zenker in Cameroon. The posters displayed the head and shoulders of the gorilla, including dramatic facial expressions, next to the wording ‘New exhibit’.

A poster printed by Friedländer in Hamburg for the 1903 German Colonial Hunting Exhibition in Karlsruhe – to advertise Umlauff’s primate taxidermies. (Deutsches Plakatmuseum Essen, DPM 4393. All rights reserved.)

This was a continuation of the trophy iconography depicting the gorilla as a beast, which also legitimised the killing of the animals and, in a figurative sense, the subjugation of humans in the colonies who had also been declared ‘savage’. It was translated into various media – paintings, posters, taxidermies, and later films like King Kong (1933) – with slight variations. While the stereotypical image of Earth’s largest primate as a beast has survived into the present, its historical entanglement with colonial power fantasies and exhibition contexts has now largely been forgotten.

- The picture without a stamp by Wilhelm Kuhnert (who also exhibited in Karlsruhe) is also printed in Umlauff’s Gorilla brochure. Cf. Der Riesen-Gorilla des Museum Umlauff Hamburg: Schilderung seiner Erlegung und wissenschaftliche Beschreibung. Katalog. Hamburg: Adolph Friedländers Druckerei, 1901.↩

- “Deutsch-Koloniale Jagdausstellung in Karlsruhe”. Deutsche Kolonial-Zeitung 20, no. 29 (1903): 291.↩

- Cf. Hans Werner Ingensiep. “Kultur- und Zoogeschichte der Gorillas: Beobachtungen zur Humanisierung von Menschenaffen.” In Die Kulturgeschichte des Zoos, Lothar Dittrich, Annelore Rieke-Müller, and Dietrich von Engelhardt (eds.). Berlin: VWB, Verl. für Wiss. und Bildung, 2001: 151-170.↩

- Cf. Ingensiep, 2001: 153.↩

- J.F.G. Umlauff to P. Matschie, 09.06.1903, MfN, HBSB, ZM-S-III, Umlauff, J.F.G., Bl. 23.↩

- The Umlauff company also provided taxidermies of other primate species in addition to its gorilla taxidermies.↩

- G. Zenker to P. Matschie, 02.09.1903, MfN, HBSB, ZM-S-III, Zenker, G. and H., Bd. I, Bl. 220/221.↩